[…] all that we behold

From this green earth; of all the mighty world

Of eye, and ear,—both what they half create,

And what perceive.

Wordsworth, “Tintern Abbey”

Whether your sunglasses are off or on

You only see the world you make.

John Hiatt, “A Thing Called Love”

I’ve just finished at a former student’s strident insistence the Hungarian novelist Sándor Márai’s last work, Portraits of a Marriage. I don’t know if we lose something in the translation of the title, but the narrative might more accurately be dubbed: Satellites of Love or Chain, Chain, Chain of Partners or A Sociological Study of Class Relationships in Hungary from 1930 – 1950.[1]

The thing is that no title can do justice to the mighty compression of meaning that the novel holds. Divided into four parts, the narrative unfolds in the style of a Robert Browning dramatic monologue, with each section narrated by a different character. We are in a concrete setting, a bar or bed, and along with us there is someone listening to a monologue, but we never hear that person speak. Instead, we get remarks like: “Sorry . . . What did you say? Why I started weeping when I saw him just now?”

This auditory technique may be off-putting in a culture dominated by visual imagery where we expect cinematic quick cutting, and I admit the conceit does add a bit too much ballast to suspension of disbelief; however, the articulation of the perceptions of the first three monologists is at once meaningful and conversational.[2]

It begins in Budapest between the wars. Here is Ilonka, the first wife of Peter, an industrialist, describing to a female companion her reaction to finding a decades-old love token in her husband’s wallet, a token that predates her relationship with him:

And now I knew that whatever wonderful or terrible things were happening in the world, it was pointless to accuse myself of selfishness, lack of faith, lack of humility, pointless comparing my problems to those of the world of nations, the problems of millions suffering their various tragedies, because there was nothing I could do – selfish and petty as I was, obsessed and blind as I was – except to get out on the street and search out the woman I had to confront face-to-face, the woman I had to talk to. I had to see her, to hear her voice, look in her eyes, examine her skin, her brow, her hands.

We can’t blame Peter for fleeing such suffocating obsession, and in the second section he tells a colleague what that first marriage was like and how he fared in his second marriage to a servant girl of his household named Judit, the girl who had given him that token, a peasant who literally grew up in a ditch. In England, after she leaves the household, she transforms herself into a highly credible Pygmalion-like creature who knows which fork to pick up. Upon her return, Peter defies social convention and marries this underclassling.[3]

Here is Peter describing the object of his obsession:

It wasn’t a “lady” or a glittering socialite I yearned for. I hoped for a woman with whom I could share a lonely life. But she was terrifying ambitious [. . .] wanting to conquer and take occupation of the world.

The only things she fears is

[h]er own hypersensitivity to offense, some mortal wound to the pride glowing in the depths of her life, her very being. That was what she was afraid of, and everything she did by word, silence, and deed was a form of defense against it. It was something I could never understand.

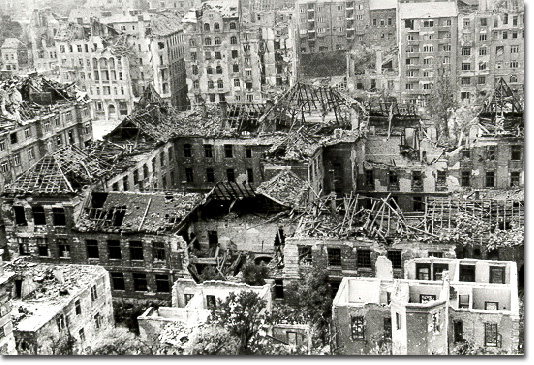

So what we have here is the Rashomon effect, contradictory accounts of the same event. In the course of these dialogues a quarter of a century passes; we see the class stratification of Hungary before the war, Budapest’s leveling during the war, and its Soviet occupation after the war. All of our principals but Ilonka become ex-pats.

It’s Judit who devours the narrative scenery, talking to her latest lover, a jazz drummer whose stage name is Ede. They’re in Rome in a hotel bed after one of his gigs. Judit possesses the most experience, having risen from abject poverty to enormous wealth. She’s the least socially conditioned one, and she is able to look upon the events of her life with a sort of anthropological detachment:

High culture, it seems, is not just a matter of museums but something you find in people’s bathrooms and kitchens where others cook for them. Their way of life did not change, not a bit, not even during the siege, would you believe it? While everyone was eating beans or peas, they were still opening tins of delicacies from abroad, goose liver from Strasbourg and such things. There was a woman in the cellar, who spent three weeks there […] on a diet, a diet she maintained even when the bombs were falling. She was looking after her figure, cooking some tasty something on a spirit flame using only olive oil because she feared that the fat in the beans and gristle everyone else stuffed themselves with out of fear and anxiety might lead her to put on weight! Whenever I get to thinking about it, I marvel what a strange thing this thing called culture is.

There is one other character, Lazar, who doesn’t get his own monologue but who appears in every section. He’s a writer, perhaps Márai’s alter ego. Of course, I identify with him because, not only is he bald, but he’s also a pessimist (and who wouldn’t be scrounging around a bombed out city). He has several quotable passages throughout, but I’m going to have Judit describe him instead of having him speak for himself:

What’s that? Was he a snob? Of course, he was, among other things, a snob. He couldn’t stand being helped because he was solitary and a snob. Later I understood that there was something under this snobbish manner of his. He was protecting something, trying to preserve a culture. It’s not funny. I expect you’re thinking of those olives. That’s why you laughing? We proles, we don’t really get the idea of “culture,” sweetheart. We think it’s a matter of being able to quote things, of being fussy, of not spitting on the floor or belching when we’re eating, that kind of thing. But that’s not culture; it’s not a matter of reading and learning facts. It’s not even learning to behave. It’s something else. It was the other idea of culture he was wanting to protect. He didn’t want me to help him because he no longer believed in people.

As I was reading through the individual sections, I found myself put off by these people’s egocentricities, their obsessiveness, but once I got halfway through Judit’s monologue, the cumulative effect suddenly came upon me like revelation. What we have here is a deep meditation on love, loneliness, obsession, culture, family, and perhaps most profoundly, the limitations of personal observation. The gulf between these people’s perceptions of themselves and others’ perceptions of them is an unbridgeable breach.

This might not be a great novel – I won’t judge until a second reading – but if you’ve reached this final sentence, you’re likely to find it worth your while.

[1] In Spanish the title translates into “The Righteous Woman”

[2] The 4th narrator Ede, a jazz drummer-cum-bartender, lives in “a pad.”

[3] Let’s not forget that Hunagry in the early part of the previous century was not L.A. I can’t come up with a good analogy. Prince Phillip marrying Billie Holiday?

Sándor Márai as a child

Share this:- Share