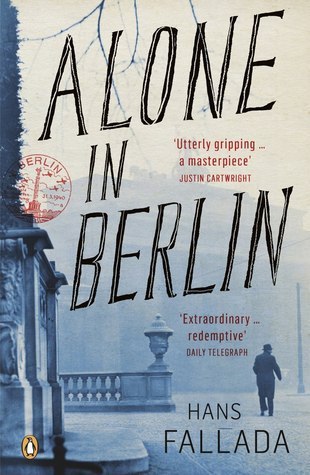

My first post on Alone in Berlin, which I read for German Lit Month is here.

Spoilers ahead…

“People with a faith have an easier time of it nowadays, I’m sure. They have someone they can turn to with their worries. They think all this killing is for a reason.”

“Thanks!” said Quangel, suddenly vicious. “A reason! It’s all senseless! Because they believe in heaven, they don’t want to fix anything on earth. Always crawl and keep a low profile. Heaven will fix everything. God knows why it’s happening. On the Day of Judgement we’ll find out. No, thanks!”

Otto Quangel has changed. Writing postcards has changed him. He is still laconic, private, but the postcards are filling him with indignation, restlessness, and questions which he can answer. In a rare conversation with his wife Anna, he dismisses the presence of God. He observes that if there was a God, how could He allow the genocide. Otto is meditating on that theme for us, the readers. He is trying to pin down an answer for the questions that we all ask whenever we read about the Holocaust — What was God doing?

Otto Quangel has changed. Writing postcards has changed him. He is still laconic, private, but the postcards are filling him with indignation, restlessness, and questions which he can answer. In a rare conversation with his wife Anna, he dismisses the presence of God. He observes that if there was a God, how could He allow the genocide. Otto is meditating on that theme for us, the readers. He is trying to pin down an answer for the questions that we all ask whenever we read about the Holocaust — What was God doing?

Anna is torn between her husband and God. She could be more rebellious and more opinionated than Otto, but she wants to alleviate their pain by applying the balm called God, even if He is taking them to the guillotine. Later, her Faith mutates into her unwavering love for her husband; she draws strength from that well to survive the final wait. The solitude might be making her cold and suicidal, but her only light is Love. The light of all lights.

Now he learned that this back-and-forth of wooden figures could bring something like happiness, clarity in one’s mind, a deep and honest pleasure in an elegant move, the discovery that it mattered very little if you won or lost, but that the pleasure of losing a closely contested match was much greater than that of winning through a blunder on the part of his opponent.

The insanity of Nazi cells challenges Anna’s determination and courage, but it makes Otto more sane. He enjoys the company of his cellmate (that is out of his character), establishes a routine which includes fitness, and even learns to play Chess. He is so close to death. But he feels free and more alive than ever. He reflects that he never knew that life could be this exciting — the most beautiful irony that Hans Fallada nonchalantly offered in Alone in Berlin.

Hans Fallada is ruthless. He borrows Hitler’s axe to kill almost every good soul in the book. I wanted Judge Fromm to live even after Otto and Anna, but in a pair of brackets, Fallada says that Fromm’s house is bombed three years later. I died a little. But the last chapter is the much-needed resurrection. All the old souls might have lost their lives, but Fallada plants Hope in a young soul, who flees Berlin. That boy could have become an easy victim or one among the Nazis. However, Fallada drops him with an endearing couple; he grows up in a farm, he is educated, he knows love, and maybe, he is the symbol of the Germany that the Quangels and the Judge desired.

PS: My edition features the postcards written by the real couple and some notes from the interrogations. I shuddered when I read the cards. They were prosaic, but what made them powerful was what the couple risked to write and drop them. Heartrending!

Advertisements Share this: