Meg Medina is an award-winning Cuban American author who writes picture books, middle grade, and YA fiction. Her work examines how cultures intersect, as seen through the eyes of young people. She brings to audiences stories that speak to both what is unique in Latino culture and to the qualities that are universal. Her favorite protagonists are strong girls.

Meg Medina is an award-winning Cuban American author who writes picture books, middle grade, and YA fiction. Her work examines how cultures intersect, as seen through the eyes of young people. She brings to audiences stories that speak to both what is unique in Latino culture and to the qualities that are universal. Her favorite protagonists are strong girls.

Among the many praises her work elicits, the Américas Award has acknowledged her exceptional contributions to Latin American and Latino literature for children and youth. Titles that have appeared on the Commended Lists for the Américas Award include Burn Baby Burn (2017) and Yaqui Delgado Wants to Kick Your Ass (2014).

Here, the author converses with Hania Mariën of the Vamos a Leer blog as she poses questions about Medina’s work, her inspirations, and the importance of bringing Latinx literature into the classroom. For more information, including publications and supporting educational resources, visit https://megmedina.com/

June, 2017

HANIA MARIËN: According to your website, a lot of your work focuses on supporting girls, reaching out to Latino youth, and fostering literacy. Can you talk a bit about how and why you are interested in these topics and how your work as an author and educator supports these intersecting efforts?

MEG MEDINA: That’s a big question. Like everyone else, I’m a composite of interests and influences. I was raised in a house led mostly by women, so there was a distinctly female lens on things. My mother and aunts had been teachers in Cuba, so there was always an interest in literacy and learning, too – not to mention an immersion in Cuban culture and customs.

As for feminism, I’d say that my interest sprang from being a child who came of age in the mid 1970s, which was a golden age of feminism in New York. This was the time of Ms. Magazine, Gloria Steinem, Bella Abzug, and the first Women’s International Congress.

I’ve stayed interested in these topics because they shaped me. I occupy this world as a female and a Latina – it’s the only set of eyes I have. What I’ve chosen to do with that perspective is to turn it into an art form and to use that art form not only to understand myself better, but also to help build pride, connection, and resilience in young readers.

HANIA MARIËN: Can you elaborate on your process of trying to write for and about Latinos? In an interview with Publishers’ Weekly, for instance, you acknowledged the diversity of Latino and Latin American cultures and the difficulty of trying to write about that breadth of perspectives.

MEG MEDINA: I think the umbrella term “Latino” is so very broad. It encompasses many countries, races, economic realities, and experiences. But which stories get told and by whom? What gets to be called authentic representation?

As an author, what I try to bring to my work is an honest look at the bicultural Cuban American experience, as I lived it. Some of the characters and situations in my novels transfer easily to other immigrant groups, particularly from Latin America, and I’m glad for that. These include the struggle to separate from the parents’ culture; language issues; trying to get a footing in a new country; and facing down overt and veiled racism.

But my work is not nearly enough to tell the whole story of Latinos. For that you need many more perspectives. My dream is to see many more authors add their stories to what is available for children, so that we can start to see the true tapestry.

HANIA MARIËN: Many of your books feature strong women protagonists. Can you speak about your definition of feminism and how feminism informs your writing and outreach efforts?

MEG MEDINA: I am proudly a feminist, and I define that as a celebration of women who are strong, independent, and equally valued in their homes and the larger society. I write books that celebrate girls, particularly Latinas, as they work on their resilience and their own voice. To that end, I reject stereotypes of Latinas which are, sadly, everywhere in books and other media. Girls clad in tight, cheetah print clothes. Girls who are written as hot-tempered and overly sexualized, as gang members, as drop outs, as victims. The list goes on. I write to expand the narrative to include the real women I knew and to honor the young women in classrooms that I meet every day. They’re smart. They have agency. And they deserve nuanced and respectful representations of who they are.

HANIA MARIËN: You’ve written that you are an “author of libros for kids of all ages.” This calls to mind your fluid ability to move between Spanish and English. Can you speak about being bilingual and what bilingualism has meant to you personally and professionally?

MEG MEDINA: I think and speak in two languages, and the line between the two is anything but static. The reality of Latino families is that language is fluid. For example, perhaps grandparents speak only Spanish, parents speak both – to varying degrees – and maybe the child can speak Spanish and English, but not read or write both. Or perhaps the child doesn’t speak Spanish at all. Or maybe Spanish isn’t the home language. The possibilities are endless. Families still communicate, though. So, I like to capture the mixture of Spanish and English that forms the practical way that we speak to each other in our homes. I love, too, to see the phrases that are borrowed from each language and how they impact each other. Some people complain that the use of Spanglish is distracting, but to whom, exactly? Not to me. So, I’m unapologetic. Language is always evolving and we have to adapt. What was a selfie 20 years ago? What was fake news before last year? These are new expressions that reflect what’s happening. Language expands to make room for them. It works the same with Spanglish phrases.

HANIA MARIËN: It sounds like it’s not uncommon for you to speak directly with the students who are reading your books. What are some of the lessons or insights you’ve learned from speaking with them? Have they changed the way you write or informed your process in any way?

MEG MEDINA: Meeting students in person is always a highlight, and it’s always a confirmation of what I know to be true: That growing up is hard, and that young people want to have a voice in what is happening around them. Classrooms are far more diverse than they were when I was younger, so I like to recreate worlds that reflect the true friendships, complex families, and strains that exist for them now.

I like to see my work connect with all kids, but it’s true that it’s especially satisfying when I see Latino kids feel proud or simply seen for the first time in a classroom where my books are being read. In those scenarios, they become the classroom experts and can translate phrases or explain why something is happening, or add in a meaningful way to the discussion about things that their classmates might be unfamiliar with. It elevates kids to a place of power over their own knowledge and story.

HANIA MARIËN: In an interview with the Ezra Jack Keats Foundation, you say that the stories of your heritage gave you a “sense of place in history and in my family, a sense of what I came from, and a sense of my family’s strength.” Do you have any advice for educators who want to help students understand their own histories? And how reading diverse literature might help them learn and understand their own stories better?

MEG MEDINA: I think your school and classroom library should be as wide ranging as possible and should represent as many world views as possible. It’s our strongest path to creating young people who are empathetic and thoughtful about others. Comb the lists of winners of the Pura Belpré, the Tomás Rivera Award, the Américas Award for Literature, the Coretta Scott King, the Asian Pacific Writers, American Indian Youth Literature awards. You can find links to all of them on the ALA home page, but this is where you’ll find the very best examples of literature that speaks to a wide range of points of view.

My only caution is remembering not to rely solely on making a single child the ambassador for a whole culture. What you’re after is a classroom full of children that are opening the curiosity and understanding of other people.

HANIA MARIËN: You’ve long been involved in the We Need Diverse Books movement and organization. Can you talk a bit about the meaning of the phrase, “diverse books,” and their importance in the classroom?

MEG MEDINA: Some people use the term diverse to mean books featuring people from a range of races, but I use the term to mean a full scope of experiences beyond simply race and culture to include LGBTQ, disabilities, and more – all the experiences that you are very likely to find at some point in a classroom today.

It’s important to include books that speak the experience of these various communities – especially if they are written by authors who have lived those experiences. Without space on your shelves for such books, we create the impression that only some people matter or that only some experiences are worthy of consideration. The fact is that children are not going to school in a bubble, and they won’t become adults who live in a bubble either. They will work, live, and play with a full range of human beings. Books give readers important information and understanding, even if it is fictionalized.

HANIA MARIËN: In regards to the same, do you think the recent push for diverse books has a risk of passing away as some trends do? Are there concrete ways that we (as readers, writers, educators, students, and more) can help make the commitment a long-standing one among publishers?

MEG MEDINA: I doubt it will pass. A trend is fleeting. But a societal shift in population is another thing entirely. And that’s what the statistics tell us that we have in the US.

So, as educators, what are we planning to tell the ever-increasing number of so-called minority students? That there are no books that represent them? Are we going to cling to collections and reading lists that reflect an earlier time or one that reflects the world we actually live in?

As educators, as parents, as community leaders, we need to purchase a wide range of books, invite a representative range of authors to our schools, encourage eclectic reading tastes in young people so that they can move through their world prepared.

HANIA MARIËN: Thinking about what lies ahead, are there any projects you have in the works that you can tell us about?

MEG MEDINA: I have a new middle grade novel due out in the fall of 2018. It’s based on characters that I developed for a short story that I wrote for the We Need Diverse Books anthology, Flying Lessons and Other Stories. And, I’ve been keeping my eye on things as Yaqui Delgado Wants to Kick Your Ass is developed as a TV series on HULU. The producers are the fabulous Gina Rodriguez and Eugenio Derbez – and the writer is Dailyn Rodriguez, who wrote for “Ugly Betty” and other well-known shows. I’m thrilled that it’s Latino talent all the way through.

HANIA MARIËN: In your interview with the Washington Post you mention that we need editors, marketing people, book reviewers, etc. with “wider sensibilities.” You also mention we don’t know our own “blind spots.” What role can books play in helping us – as educators and students of the world – learn about our blind spots?

MEG MEDINA: I think that reading and following critical discussions about books offer educators a chance to deepen how they select and evaluate a book for a collection. You may have loved Little House in the Big Woods as a child, but if you read it as an adult, you’ll find some troubling dialogue. The same is true for Harriet the Spy and any number of beloved classics. But it’s not just a problem of past works. Unfortunately, we still have books written today that use language, illustrations, or situations that are offensive to the groups being portrayed.

I think that supporting books that are written by #ownvoices authors is one step in the right direction.

The other step is to go beyond quick assessment of a book. We’re all busy, so it’s easy to flip through a review journal to see if a book got stars.

But these days, you need more. By following the sometimes-gut-wrenching arguments about new books, you can learn how to ask yourself harder questions about books and how not to gloss over something offensive simply because you never thought of it as problematic before. You learn to look beyond the reviewing agencies to find out if a book is raising red flags on offensive content. You learn to tune in to the people from groups whose stories have been told incorrectly or boorishly, and you develop a more respectful way to assess the quality of books representing that experience.

No one gets everything right all the time. And some disagreements will stay just that: disagreements. But the dialogue matters and the overdue shift if respect is essential.

HANIA MARIËN: Finally, as the child of immigrants yourself, are there any words of advice or inspiration you can offer to the educators out there who may have young immigrants in their classrooms? In these particularly contentious and troubling times, what might they do to better support immigrants and refugee children?

MEG MEDINA: I think we are at risk of traumatizing immigrant children right now. Imagine being thought of not as someone who adds value to a classroom, but as a drain, a criminal, a scourge.

As educators, our number one job is to create a space where children can feel safe to learn. One way to do that is to celebrate the people they are, to celebrate their families and the perspectives they bring to us. If ever there was a time for literature that focuses on the universal qualities of families and growing up, it’s now. Look at your students. Who are they? Now, go find as many books as you can that includes them in the pages.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

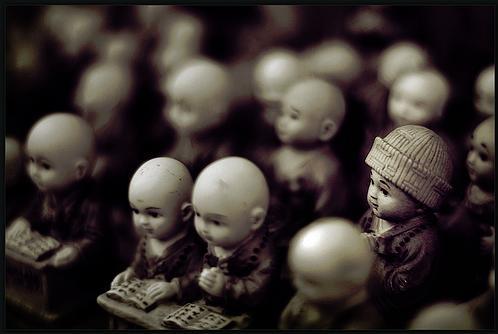

Photograph of author. Reprinted courtesy of Petite Shards Productions.

Share this: