While I realize it was only two weeks ago when I wrote about finding four Last Address memorial plaques in my neighborhood I had not seen before, I would like to document another six plaques I found today, because I do not think it is enough to know they are out there somewhere. Instead, we should pause for a few minutes and read the bare facts on each plaque out loud or silently. It is also important, given the current frightening atmosphere in Russia, to show passersby that they, too, can stop and honor the victims of Stalin’s Great Terror in this way, as well as to share this witnessing and remembering with readers out in the big wide world, whoever and wherever you are.

Of course, Last Address will only be complete when there is a plaque or plaques on every one of the 341,582 addresses in Memorial’s database.

While that day seems far off, it is surprising how quickly Petersburg has filled up with Last Address plaques in a mere two or three years.

The plaques my companion and I found earlier this evening were attached to the streetside façade of the building at 146 Nevsky Avenue, the segment of Nevsky, east of Insurrection Square, known to locals as “Old” Nevsky.

The plaques have been placed on the building at eye level and are thus quite easy for passersby to notice, read, and photograph.

The building itself is a hybrid of two eras. First built in 1883 by Valery von Gekker to house the Menyaevsky Market, the building was rebuilt and expanded in the constructivist style by Iosif Baks in 1932–33, turning most of it into a block of flats.

146 Nevsky Avenue, Petersburg. Photo courtesy of citywalls.ru

146 Nevsky Avenue, Petersburg. Photo courtesy of citywalls.ru

When the six people memorialized on the plaques lived in the building, Nevsky was still known as October 25 Avenue, the name it bore from 1918, after the Bolsheviks came to power, until January 1944, when residents asked the authorities to restore a number of old street names in the city center to mark the lifting of the Nazi Army’s 900-day siege of the city.

The address listed on the Last Address map is thus 146 October 25 Avenue, as it would have been listed in the NKVD case files of the victims at the time.

“Here lived Mikhail Pavlovich Kovalyov, welder. Born 1887. Arrested 30 October 1937. Shot 7 December 1937. Rehabilitated 1958.” Born in the village of Raivola, Finland, near the Russian/Soviet-Finnish border, Mr. Kovalyov worked at the Khalturin Factory and lived in flat no. 186.

“Here lived Mikhail Pavlovich Kovalyov, welder. Born 1887. Arrested 30 October 1937. Shot 7 December 1937. Rehabilitated 1958.” Born in the village of Raivola, Finland, near the Russian/Soviet-Finnish border, Mr. Kovalyov worked at the Khalturin Factory and lived in flat no. 186.

“Here lived Vaclav Adamovich Zaikovsky, litographer. Born 1897. Arrested 31 August 1937. Shot 21 November 1937. Rehabilitated 1957.” Born in the Vilna Governorate of the Russian Empire, Mr. Zaikovsky was a member of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) from 1917 to 1937, and director of the First Art Lithography Works. He lived in flat no. 163.

“Here lived Vaclav Adamovich Zaikovsky, litographer. Born 1897. Arrested 31 August 1937. Shot 21 November 1937. Rehabilitated 1957.” Born in the Vilna Governorate of the Russian Empire, Mr. Zaikovsky was a member of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) from 1917 to 1937, and director of the First Art Lithography Works. He lived in flat no. 163.

“Here lived Dmitry Andreyevich Yeretsky, civil servant. Born 1900. Arrested 23 September 1937. Shot 21 September 1938. Rehabilitated 1957.” Mr. Yeretsky was born in Beredichev, Belarus. He was director of the State Institute for the Design of Wood Chemical Industry Enterprises (Giproleskhim) and lived in flat no. 164.

“Here lived Dmitry Andreyevich Yeretsky, civil servant. Born 1900. Arrested 23 September 1937. Shot 21 September 1938. Rehabilitated 1957.” Mr. Yeretsky was born in Beredichev, Belarus. He was director of the State Institute for the Design of Wood Chemical Industry Enterprises (Giproleskhim) and lived in flat no. 164.

“Here lived Alexander Kirillovich Sirenko, civil servant. Born 1903. Arrested 10 February 1937. Shot 24 August 1937. Rehabilitated 1955.” Born in Ukraine’s Donetsk Region, Mr. Sirenko was director of the Nevsky Chemical Plant and lived in flat no. 146. He was a member of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) from 1924 to 1937.

“Here lived Alexander Kirillovich Sirenko, civil servant. Born 1903. Arrested 10 February 1937. Shot 24 August 1937. Rehabilitated 1955.” Born in Ukraine’s Donetsk Region, Mr. Sirenko was director of the Nevsky Chemical Plant and lived in flat no. 146. He was a member of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) from 1924 to 1937.

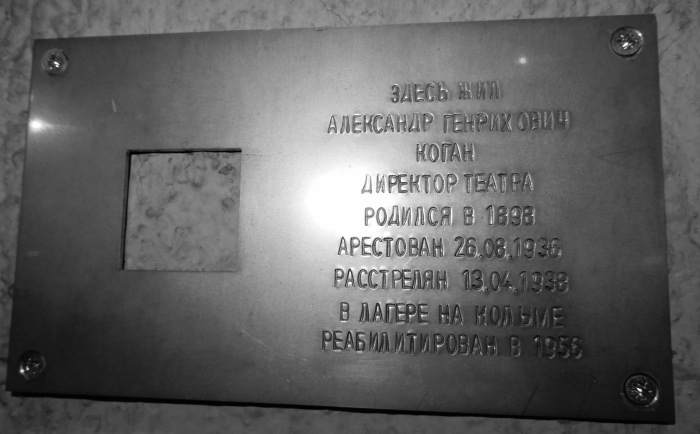

“Here lived Alexander Genrikhovich Kogan, theater manager. Born 1898. Arrested 26 August 1946. Shot 13 April 1938 in a work camp in Kolyma. Rehabilitated 1956.” A Jew from Nikolayev, Ukraine, Mr. Kogan was accused by the NKVD of involvement in a wholly fictitious “counterrevolutionary insurgent organization.” The number of the flat where he lived is not listed on the Last Address map or in Memorial’s Leningrad Martyrology database.

“Here lived Alexander Genrikhovich Kogan, theater manager. Born 1898. Arrested 26 August 1946. Shot 13 April 1938 in a work camp in Kolyma. Rehabilitated 1956.” A Jew from Nikolayev, Ukraine, Mr. Kogan was accused by the NKVD of involvement in a wholly fictitious “counterrevolutionary insurgent organization.” The number of the flat where he lived is not listed on the Last Address map or in Memorial’s Leningrad Martyrology database.

“Here lived Melania Ignatyevna Shoka, civil servant. Born 1908. Arrested 2 September 1937. Shot 1 November 1937. Rehabilitated 1989.” An ethnic Pole born in the Grodno Governorate of the Russian Empire, Ms. Shoka was a personnel instructor in the non-steamboat fleet of the Northwest River Shipping Company. She lived in flat no. 70 and was not a member of the Communist Party.

“Here lived Melania Ignatyevna Shoka, civil servant. Born 1908. Arrested 2 September 1937. Shot 1 November 1937. Rehabilitated 1989.” An ethnic Pole born in the Grodno Governorate of the Russian Empire, Ms. Shoka was a personnel instructor in the non-steamboat fleet of the Northwest River Shipping Company. She lived in flat no. 70 and was not a member of the Communist Party.

I am not an expert on the Great Terror, but I have noticed a preponderance of non-ethnic Russians and people born outside of Leningrad/Petersburg in the three hundred or so database case files I have perused. Given that the NVKD would also have had to fill its arrest and execution quotas in Central Russia, I am certain, of course, that ethnic Russians are also more than amply represented among the Terror’s myriad victims. It was just that Petersburg had been a cosmopolitan city almost from its foundation and twenty years previously had been the capital of a multi-ethnic empire. In its first two decades, the Soviet regime had also encouraged what historian Terry Martin has dubbed an “affirmative action empire.” But one of the signal victims of Stalin’s crackdown was faith in a polity that was “socialist in content, nationalist in form.” So, Leningrad’s non-Russians were easy targets for Stalin’s newfound anti-cosmopolitan paranoia.

Share this: