Over three decades ago, in 1982, I booked a private telephone consultation with an Objectivist philosopher (associated now with the Ayn Rand Institute) on reading The Romantic Manifesto, Ayn Rand’s classic non-fiction work on aesthetics.

At 24, I was both an artist and an Objectivist. A fine art major; I had taken several art history classes including contemporary art theory. At the time, I had just completed the painting Promethia, and even though it was a thematic work, I didn’t understand how one objectively identifies a theme of an artwork. With that in mind, I was excited to be mentored by an Objectivist philosopher.

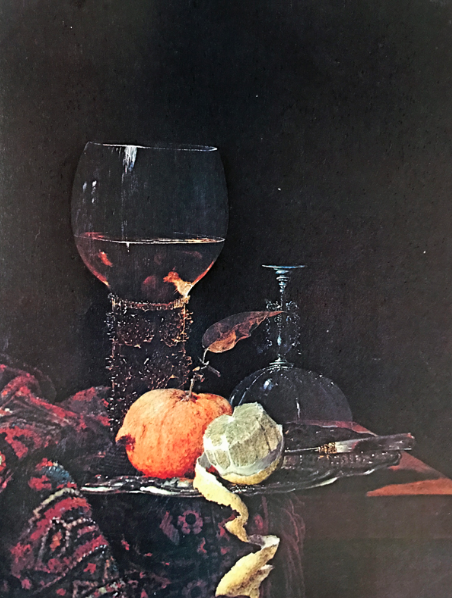

In our consultation, he pointed to Willem Kalf’s still life painting in the classic art history book, Gardner’s Art Through the Ages.

“How do I discover the theme?” I asked, genuinely.

“The theme of this painting is malevolent because of the dark background!” was the swift and vociferous response.

This was “obvious” — i.e. self-evident — he said. No further reasoning or discussion was necessary.

I ended the session and never consulted him again.

Alas, I had yet to learn how themes work in painting. So I returned to what Ayn Rand herself had written.

In the Romantic Manifesto she writes:

“Now a word of warning about the criteria of esthetic judgment. A sense of life is the source of art, but it is not the sole qualification of an artist or of an esthetician, and it is not a criterion of esthetic judgment. Emotions are not tools of cognition … In essence, an objective evaluation requires that one identify the artist’s theme, the abstract meaning of his work (exclusively by identifying the evidence contained in the work and allowing no other, outside considerations), then evaluate the means by which he conveys it—i.e., taking his theme as criterion, evaluate the purely esthetic elements of the work, the technical mastery (or lack of it) with which he projects (or fails to project) his view of life.”

—Ayn Rand, Romantic Manifesto, Chapter 3: Art and Sense of Life

To discover the theme of a painting, you have to observe almost everything about it, catalog it, and find the common denominator among those things that unites them. Then when you know what the painting is about you have to persuade the viewers and yourself that indeed that is the theme of the painting. Also, it takes the observer some knowledge in art technique to note the successful execution of the theme.

In Kalf’s painting, we have exquisitely painted glasses with beautifully crafted metal stems. Ornate silverware. A luxurious table carpet, which is typical in Holland, even in today’s pubs. And a small pumpkin and a beautifully cut lemon. The background is dark which offsets the light on the pumpkin and the lemon, emphasizing their lightness and color.

Notice the ellipse on the top of the glass: It is delicate and superbly done! Notice the form of the carpet and how it pivots towards us giving us a sense of spatial contrast between the foreground and background. We can tell from the light and the shadows that the light source is coming from behind and above our left shoulder. Notice the shadows and the bright illumination of the lemon.

The subject of the painting is some of the finer things in life: good drink, fine craftsmanship, and fresh produce. The tantalizing lemon and the silverware suggest that there might be fish roasting. The means of conveying the subject are spot on in perspective, precision, clarity, and a very dramatic use of light and dark. Imagine a banker, merchant, or a professor (has to be a person of some means to afford the finery): After working a day of solving problems elegantly they come home and are met by the rewards for their efforts. I would say the theme of this painting is “rewards,” and I would title it as such.

While I was painting Promethia, the work above, prior to my consultation with the Objectivist philosopher, I was certain about the feeling and the vision driving it. Putting it into words the famous quote by Nietzsche serves best: “The noble soul has reverence for itself.” Conveyed through my ideal pairing of figurative sculpture, modern architecture, and nature.

Themes in painting are not absolutes and they have to be tried on and confirmed by what the paintings show us. There is no room for knee-jerk dogmatic judgments; understanding comes one step at a time through each individual’s lens.

Michael Newberry

Originally published with The Atlas Society

Share this: