SOMA is a science-fiction game made by the same developers that made the Amnesia games. Unlike Amnesia, however, SOMA is light on the monsters and heavy on the existential angst. We play as Simon Jarret, a bookstore employee with serious brain damage, who participates in an experimental brain scan meant to lead to a cure for his condition. The next thing we know, Simon wakes up in a bizarre undersea city called Raptu – I mean, Pathos-II.

It turns out that Isaac’s brain scan has been imprinted onto a robot with human-like capabilities roughly 100 years in the future. The “real” Simon Jarret died long ago from his car accident injuries. This realization is, admittedly, a really amazing scene in video games. It’s depicted in the featured image for this article above. Basically, robo-Simon thinks that he is the real Simon from 2015, even looking in a mirror and seeing Simon’s face, rather than the robotic face that robo-Simon really has. But eventually, as the evidence as to his true existence piles up, robo-Simon looks in the mirror again. This time he actually sees the real robotic form that he inhabits.

The idea is that people are limited to seeing what they expect to see. Simon can’t see himself as a robot until he comes to accept that he is a robot. Similarly, many of the sentient robots you find throughout the facility believe that they are human, because they are human personalities stuck in a robot body.

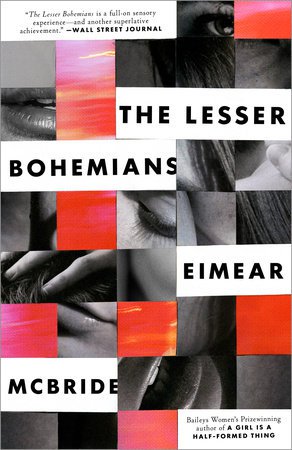

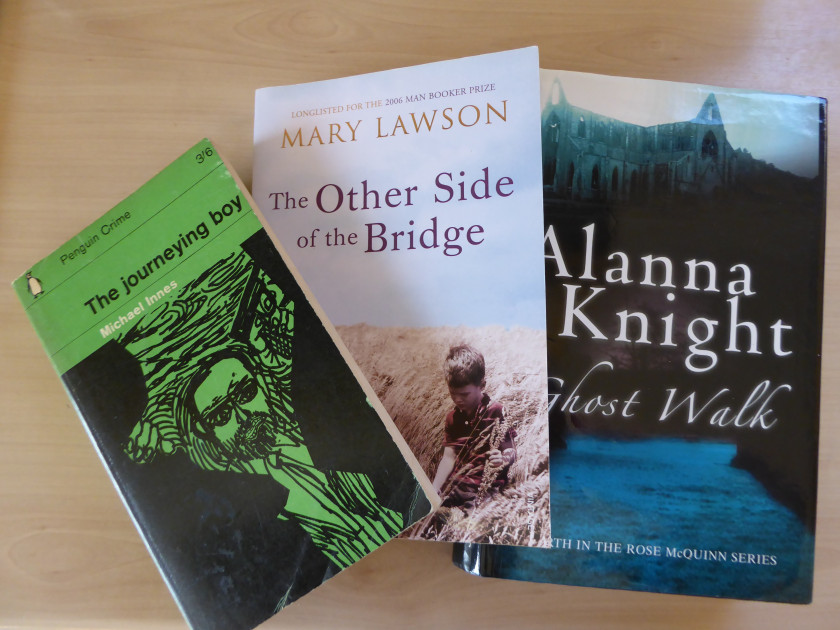

SOMA is an interesting study in how our perceptions shape our reality. The opening quote of the game is “Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away”, a quote from science-fiction author Philip K. Dick. Dick was also known for exploring such themes in his works, notably in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, the novel that inspired the film Blade Runner (plus its new sequel).

I think it’s worth referring to this particular novel and the film Blade Runner as mirrors of what is going on in SOMA, since they share so many themes.

So go get those and read and watch them.

I’ll wait here.

Or you can ignore me and just keep reading, you lazy rebel.

The novel in particular discusses the blurred lines between humans and identical androids, both being “electrical things” with “paltry lives” as Deckard (the protagonist) comments at the end. The novel suggests that what a being believes they are might make them into that thing, so an android that believes itself to be human might be able to become human. There is also an implication that the more mechanical and technological people’s lives become, the less empathy they have, and thus the less human they become. Humans then become androids, things that look like people but lack human characteristics.

It might also be worth commenting that paranoia over the seemingly human, but actually inhuman, runs back a lot further. From mythical golems, to tanuki impersonating humans, to alien bodysnatchers, or even zombies (!), there are many stories and myths that consider the unsettling idea of something that impersonates a person but is actually not. A human body without a human soul inside it.

But why do we care? Why does that idea bother us? My interpretation of this is somewhat similar to Dick’s: empathy. We want to know that people we are dealing with will consider our wants and needs, and will care about us enough to not do us harm. It’s a self-defense measure.

So back to SOMA. Pathos-II housed a number of stupendously unlucky people at the bottom of the ocean, making them the sole survivors of the apocalypse on the above ground world. It’s basically a little metal city, filled with computers and robots, so we see that this is a very mechanical world, like the one in Dick’s novel. The people in this world, faced with the loss of the above world, and their own imminent deaths, find themselves seeking for solace. They don’t want to die pointlessly, deep in the dark abyss of the ocean. They want transcendence.

They thought that they had found this in the research that led to the creation of a digital world, a perfect digital world, where everyone’s digital selves can be happy forever. They were going to launch this mythical WoW server into space and those little digital bytes would float around being happy for all eternity.

Now, I have to be honest here, this immediately struck me as very dumb and it still does. Obviously, if you put a copy of yourself into a digital world, that does you no good whatsoever! They mention the “coin flip” thing a few times, but it doesn’t really make sense. There is the origin of the copy and the copy itself. The copy goes into a new body and is a new creation, a “child” of sorts, of the original (which might also be a copy of something else). The original has no way of going where the copy goes, so the Simon in a robot body can never ever get into the perfect digital world. He’s screwed no matter what, just like the copy you leave behind in the broken suit earlier.

But anywhoo, I don’t want to harp on that too much. It’s still an interesting idea (even if the concept is faulty). The idea is that these beings are seeking a nirvana in a digital world. But that raises a problem: none of it is real… right?

There’s essentially a database floating in space. That’s the physical object. But inside that database, programs are living out what seems (to them) a full life. Is it real?

In my opinion, no. The problem with this whole concept is that the human body is not solely made up of electrons running through metal (that’s how my non-technical mind understands machines btw). The human body has this whole cocktail of chemicals, hormones, and impulses that – put together – create this indefinable thing we call “the soul”. Which is a whole other can of worms. But, in my view, trying to “program” a soul is like trying to spell the way a flower smells: you’re using the wrong language.

And besides, if AI can’t play Civilization properly, it will never manage to have emotions.

As someone smart once said, a human being is “a ghost driving a meat covered skeleton made from stardust”. I don’t know who that person was, but they were clever and deserve a sticker. The human experience is… weird. It’s kind of out of place, and strange, and it certainly doesn’t fit into a program or a database.

So yeah… I played this game twice, and in all honesty, I didn’t really like it that much. It has some interesting ideas, but I find the basic concepts so ludicrous that it doesn’t really mean much to me. Obviously, that’s just my opinion (cue crazed internet guy who curses a lot and likes to tell people their opinion is invalid because he has been playing Call of Duty since before it was popular. There’s always that guy.)

Thanks for reading! I apologize for my periodic absences. My studies take up a lot of my time, preventing me from posting.

More articles to come!

Advertisements Share this: