How different would most ‘great lives’ look if seen through the eyes of their servants and sub-ordinates! How odd, how trivial, how inefficient at times! They shatter myths, change perspectives and re-evaluate understandings. And above all they certainly make those ‘great lives’ look more human. In today’s post, Tanmoy Biswas ventriloquizes as Virginia Woolf’s maid. And Babita Chakraborty shares her reading of Alison Light’s book Mrs. Woolf and the Servants.

“Mrs. Woolf has some illness. When one of us is cleaning the room (if she allows us to enter and we can make our way through littered papers everywhere) we have often noticed her looking lost, cigarette burning stuck in fingers, talking on her own. Sometimes there is a big row with poor Mr. Woolf persuading her even to eat or knocking on her door if she has not come out for days. Puts our nerves in jitters. Mommy used to say, woman folks reading books never do any good to their heads.

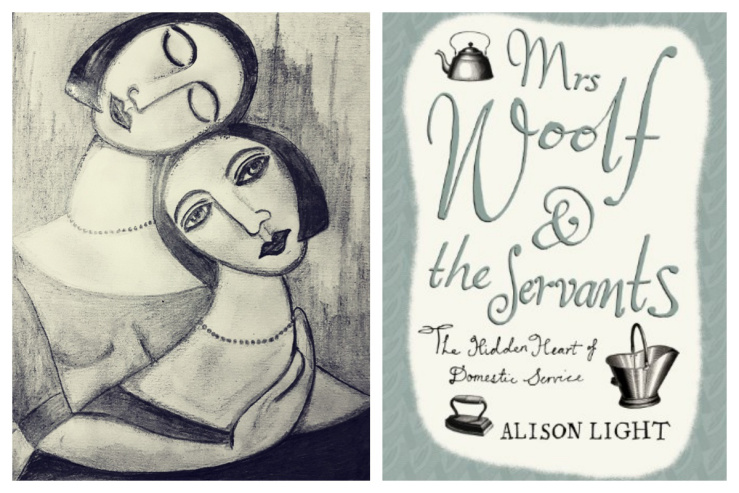

Painting by Prapti Roy

Painting by Prapti Roy

But when she is in the press downstairs or when the friends come she seems quite fit. That tall bearded man who speaks in a shrill or that mouse type timid looking Mr. Forster or Mrs. Bell and Mr. Bell and the children, the house is full of mirth and chatter. You’d see Mrs. Woolf then bursting with enthusiasm and talks and gossips in that unpleasant whisper. And oh the children! She loves them. Can go on and on being jolly with them. Poor Mr. and Mr. Woolf. If they had children things would have been better. Mr. Woolf is always worrying, we know. But see her when she is accompanying him to his talks or the day she herself went for a talk with Mrs. Sackville West, she is all attention. But then back home, to her room, and sad and morose again for days. Me poor lassie not clever in book reading but doesn’t seem good to me. Today or tomorrow she might try to do it again. You know like the last time she tried. Jumping outta window… You’re thinking how I know it all. We have our ears open even if mouths shut. We know it all. We are the servants.”

Sketch by Sayanti Mukherjee and book cover from Amazon

Sketch by Sayanti Mukherjee and book cover from Amazon

My engagement with Virginia Woolf dates back to my twelfth standard. Her words from A Room of One’s Own (1929) has remained etched in my memory ever since:

“A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.”

And, that rings so true even in 2018. The incessant struggle of a woman to cope with the standards set and spaces created by a fast-paced and largely patriarchal society has only changed it character, without diminishing to any considerable extent. As a woman coming out of her teens and preparing to face the world, I had instantly taken those words as a truism and had fallen in love with the voice that uttered them. Since then, I’ve read many of her works including Mrs Dalloway, Between the Acts, Jacob’s Room, etc., and my admiration for the woman and her works has only steadily increased.

Since, exploring the life of an author often provides an interesting pathway to some unknown facets of her works, I was easily driven to Alison Light’s Mrs. Woolf and the Servants: An Intimate History of Domestic Life in Bloomsbury, a work that projects the knotted pattern of the relationship between the servants and the mistress in an early 20th century household full of domestic hubbub. It also captures their unsung emotions, their unnoticed pangs of moving away from their land, families, friends and the interdependence in the bond they shared.

Light’s book revolves around Woolf and the women who looked after her. Apart from foregrounding the ‘little, unremembered’ acts of care, this thoroughly researched book also portrays the complex forces of and the tensions involved in domestic services. Woolf’s fraught relationship with her cook Nellie, who often drove her mistress ‘mad’ is well known. What is striking is how a servant’s affiliation to a renowned master (rather mistress) often enhanced her/his honour and pride. And this is particularly evident in the character of Sophia Farrell, who took care of the Stephens for almost the entirety of her life. She worked for Woolf and her sister, Vanessa Bell and earlier for their mother.

Portrait by Suman Mukherjee

Portrait by Suman Mukherjee

But, what was the extent of Woolf’s own affinities towards and accomplishments in domestic works? While going through the pages of this book, I came across a phase of Woolf’s life when, in March 1939, Hitler and his troops marched into Prague and declared that ‘Czecho-Slovakia has ceased to exist’. Virginia listened to it and wrote in her diary, ‘Private peace isn’t accessible’. Amidst such turbulent times she often took to cooking as a sedative. That her cooking never equalled her literary craft is evident from the fact that she once mistakenly baked her wedding ring into a suet pudding. Domestic life, for Woolf became precarious when they needed to move house after fifteen years of stability. She asked Leonard: “Shall we ever live a real life again?” This ‘real life’ though didn’t seem to take the maids into account. It is somewhat ironic that how, amidst her brilliant and revolutionary articulations of feminist thoughts, Woolf remained largely indifferent to the plights of those women who spent their lives working as maids for her, how their rightful demands often became ‘hysterics’ for her.

Light, however, makes sure that the unheard ‘voices’ make their presence felt in her work. She makes the reader halt at times and makes her/him ponder on the worldview of both the parties — the mistress and the maid. She shows, how, Woolf not only had a room of her own but also enough people to look after it. They not only allowed the writer to concentrate on her work but also generated moments of literary inspiration every now and then. And Woolf not only relied on them for the daily chores, but, at times, for emotional support as well. It is this bond of inter-dependence between the mistress and the maids that shines forth throughout this book, as Light brilliantly sums up:

“All of us begin our lives helpless in the hands of others…care for us..We rely constantly on others to do our dirty work for us…The figure of the servant takes us inside ourselves.”

Title Art : Trinamoy DasNext post on 27th January

Share this:

- More