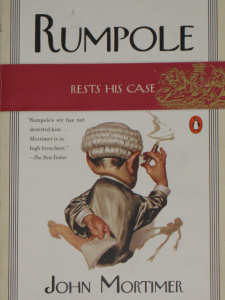

Rumpole Rests his Case

John Mortimer

Most readers, I imagine, turn to the printed word for escape, relaxation, fun.

Most readers, I imagine, turn to the printed word for escape, relaxation, fun.

Me? I’m up to my ears in newspaper columns, academic papers and social science. It’s not as though I don’t enjoy a good yarn and a belly laugh, though. Someday I’ll surprise us all and lighten up.

For now, though, let’s just visit with an old friend: Horace Rumpole, barrister.

In the British system, I gather from the time I’ve spent with Horace over the years, lawyers specialize. Solicitors handle the boring administrative parts of a case. They also find the proper advocate. That would be a barrister whose sole function is to appear in court. (I don’t think I’m out on a limb here: they appear before the bar. Hence, barrister.)

Rumpole is a veteran advocate whose practice is dedicated to criminal law. He is also (and importantly) a legal journeyman, forever a junior.

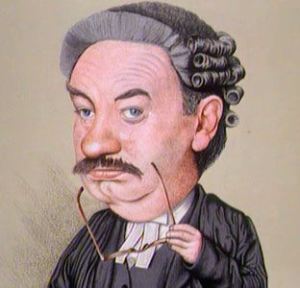

The iconic, irreverent, irracsible Horace Rumple.

That last bit does not mean our aged friend (Rumpole is to some extent a man out of time; I mentally have him fixed in his late 60s to early 70s) is less capable. In fact. one of the ongoing jokes/preoccupations in the series is how Rumpole will wrench a particular case away from a less qualified ‘silk.’

‘Silks’ ought to be the more sought after advocate since they’ve been named ‘Queens’ Counsel,’ a designation which allows them to wear a finer robe made of, well, silk. (Judges are not the only robed parties in a British courtroom, a place where both lawyers and judges wear wigs–I think peruke is the preferred term.)

From Rumpole’s vantage that’s as meaningful as a monsignor would be to one of Graham Greene‘s itinerant priests. In each case an institution is merely congratulating some portion of its members based on meeting vague (I suspect because they are completely subjective) standards. In the case of Rumpole’s silken colleagues, attaining mastery appears to lie in the eye of the beholder.

All Rumpole books (with one exception-a novel–which I have not yet read) are of a piece: several crime-related tales are told from the trial side–sort of Order and Law. In at least one tale per volume, Rumpole pulls up short, the rare hero who fails

The Old Bailey

More formally The Criminal Court of England and Wales The place where Rumpole plies his trade.

There is also usually some sort or arc, to use the television term, that runs through the stories. This go ’round the thread focuses on Rumpole’s efforts to overturn the new, and to his mind Draconian, rule about not smoking in the office.

Rumpole is a man of simple pleasures: steak and kidney pie for lunch in a pub; a bottle of ‘plonk’ (the label allegedly reads Chateau Thames Embankment) in Pommeroy’s Wine Bar; a small cigar (his beloved cheroot) to puff upon while mulling things over.

One unexpected benefit of reading Rumpole is that you’ll be taking a painless course in comparative legal systems. We’ve all seen enough courtroom dramas to be able to quickly see what the differences are and how they work.

You may even pick up some new vocabulary. If you’re like me you’ll find yourself wondering if ‘chambers,’ the more proper term for where Rumpole keeps a desk, is an improvement over the American ‘law offices,’ a puzzling term that applies even to sole practitioners. Perhaps we best leave chambers to the judges.

John Mortimer

1923-2009

Barrister, Author, Playwright

John Mortimer, the creator of our hero, was, in fact, a barrister and so the legal proceedings appear quite believable. He’s also a fine story-teller at least with what I suspect is his favorite character. I read one of Mortimer’s novels–something about Tory politics in the age of Thatcher–and didn’t enjoy it much. He also penned an interesting book about wills that was a bit macabre. I understand he is a dramatist , too, but haven’t encountered that.

In a way these stories remind me of P.G. Wodehouse and not just because of the form. There’s the ever-present tweaking of hierarchy and protocols that seem rooted in an earlier time. There’s championing the underdog. There are Rumpole’s complicated plans that, like Bertie’s, have a tendency to not work out.

There are the silly nicknames, my favorites being the private investigator Ferdinand Ian Gilmour (Fig) Newton and ‘Soapy’ Sam Ballard, the head of chambers. And who can forget Rumpole’s favorite judge, Lady Phyllida Erskine-Brown (née Trant), a former member of chambers, spouse of a hapless colleague and forever referred to as ‘the Portia of our Chambers.’

Leo McKern as Rumpole and Paricia Hodge as Lady Phlidda Erskine-Browne, the Portia of 1 Equity Court.

The whole is suffused with a gentle good humour. There’s even–and I don’t think I’m torturing the analogy–a stand in for Bertie’s aunts: judges.

Rumpole has a Jeevesian helpmeet to keep him centered, the formidable Hilda whom he affectionately calls, behind her back of course, ‘She Who Must be Obeyed.’ These two are clearly in it together for life but the manner in which they dote upon each other would easily be mistaken for something less. It’s a manner of couplehood that was passing from the scene even as I was nearing my majority.

Another similarity to Wodehouse: there’s no point recounting the stories because much of the enjoyment is in the telling. These being legal tales there’s more plot than in a Jeeves & Wooster caper but the legal case is just an excuse to tell a story about old friends.

The late, great Leo McKern

1920-2003

The man who brought Rumpole to life.

It does, however, seem obligatory to give some sense of the goings on beyond the cigar so here are a few of the cases in this volume: a man is charged with murdering his wife when a skeleton is discovered, 40 years or so after her disappearance, when the home they shared is demolished. A young man is accused of sexual assault and the evidence identifying him consists primarily of email. A celebrity who is a rehabilitated felon is shot,mistaken as an intruder with murderous intent (really?) in the home of a local gentleman.

You have to read them to see why the plots matter and yet don’t.

This is, I believe, the final volume of Rumpole stories. I’m a bit unclear as to whether Rumpole began as scripts for a television series or vice versa. Starring the late Leo McKern, the first bit aired in 1980 and a more orderly series of shows followed in the early 2000s. I recommend them and they can be found, often, on PBS or maybe in your local library.

McKern and Mortimer are no longer with us. Thank you gentlemen, for entertaining us so well.

Advertisements Share this: