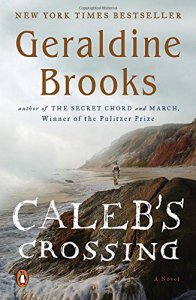

Recently while decluttering some magazines, I ran across one from Plimoth Plantation, which I must have picked up on one of my visits there. In it was an article about the posthumous degree granted by Harvard to Joel Iacoomis in 2011. That article mentioned Caleb’s Crossing. Given my (intense) interest in most things related to New England colonial history, this intrigued me.

But let’s back up a bit. Who was Joel Iacoomis, anyway? One of the first Native Americans to attend Harvard…in 1665. The degree was posthumous because, though Iacoomis completed his four years of coursework, he was killed at sea on his way to commencement and thus never had the opportunity to officially graduate.

It’s not well known nowadays, either inside or outside of New England, that the Harvard Indian College, founded in 1655 with money from an English missionary organization, ever existed. It stood for less than fifty years, housed the first printing press in North America, and in the end only ever admitted five students, only one of whom graduated (the others died or quit). We know, from primary sources, that the Native American students received the same classical education as the English ones. Several excelled and even outstripped their English classmates. King Philip’s War, however, pretty much finished any enthusiasm for the Indian College, and the original building was torn down in the 1690s. It’s now most likely been located in Harvard Yard by archaeologists. (See here for more.)

The focus of Caleb’s Crossing is not Joel Iacoomis (though he does appear in the novel), but his classmate Caleb Cheeshahteaumauk, the sole graduate of the Indian College. Both were Wampanoag from Martha’s Vineyard. (There wouldn’t be another Wampanoag graduate of Harvard until 2011.) Note that Brooks is not writing history – we know little about the real Caleb Cheeshahteaumauk, aside from his attendance at Harvard. Brooks also chose not to make Caleb the viewpoint character. This is, rather, a character of Brooks’ own invention, Bethia Mayfield.

Bethia is fictional, but her family isn’t. Their real name was not Mayfield but Mayhew. The patriarch of the clan, Thomas Mayhew Sr., purchased the island in 1641 and founded the town of Great Harbor (now Edgartown). His son Thomas Jr., who died at sea in 1657, was pastor to the English settlers as well as a successful missionary to the Wampanoag; he’s also the model for Bethia’s father.

The book is cast as Bethia’s diary and spans most of her life, though it focuses mainly on her young adulthood. She has a ravenous mind from a young age, and strains against the strictures of Puritan life. She picks up Latin, Greek, Hebrew and Wampanoag from eavesdropping on her father’s lessons with her older brother, and her favorite pastime is wandering about the island, far away from the English settlement at Great Harbor. On one of these rambles she meets Caleb. Thus begins a lifetime friendship, across cultures and languages – and the seeds of Caleb’s eventual decision to “cross over” into English society.

A strength of this book is its historical grounding and realism. Brooks explains her process and sources in the afterword, and has done her homework. Most impressively, she has created believable and sympathetic Puritans, rather than the usual caricatures. Brooks’ Puritans have differences of opinion, character flaws, and typical human foibles. They are neither the perfect, principled saints that some Calvinists portray them to be, nor universally bigoted religious zealots looking for witches behind every bush. Bethia is particularly well done: Brooks allows her to express dissatisfaction with her limited role as a woman and even with her religion, but does not turn her into a 21st-century feminist anachronism.

Brooks also explores the intersection between Puritanism and the Wampanoags’ religion. The questions Caleb asks Bethia about Christianity are drawn directly from missionaries’ private diaries, and thus reflect real conversations with real historical Wampanoags navigating a religious and cultural sea change. There is also variety among the Wampanoag characters’ outlooks. The Iacoomis family are early adopters of Christianity (Joel Iacoomis’ father was a real person and the first Christian convert on Martha’s Vineyard); Caleb is skeptical at first but eventually decides that the “English God” is the way of the future; while Caleb’s uncle Tequamuck, a powerful pawwaw (shaman/religious leader), sees the English God as cruel and wants nothing to do with him.

Brooks’ realism extends to her setting as well. She pulls no punches about sanitation, the ravages of disease, or how easy (and common) it was to have fatal accidents, especially for children. Bethia loses two siblings – a brother, whose leg is severed by a cart wheel, and a sister, who drowns when she gets trapped facedown in a puddle. Brooks also explores the kind of misdeeds that take place behind closed doors. One especially sad episode happens in Cambridge, after Bethia takes on an indentureship there to help pay for her brother’s education. A Nipmuc girl, Anne, identified as especially intelligent, arrives at the Latin school from the governors’ house. She behaves a little strangely, but everything appears otherwise normal – until she graphically miscarries. Based on the development of the fetus, Bethia concludes Anne could only have gotten pregnant while she was in the governors’ household. No one wants to believe this, of course, and would rather point the finger at Caleb and Joel. Then, as now, it can be tragically difficult to transcend cultural prejudices.

On top of all this, Brooks’ descriptive writing is simply beautiful. Even more so, I might add, when you’ve visited Martha’s Vineyard and experienced the setting firsthand. Here’s just a sample.

Those hot, salt-scoured afternoons when the shore curved away in its long glistening arc toward the distant bluffs. The leaf-dappled, loamy mornings in the cool bottoms, where I picked the sky-colored berries and felt each one burst, sweet and juicy, in my mouth. I made this island mine, mile by mile, from the soft, oozing clay of the rainbow cliffs to the rough chill of the granite boulders that rise abruptly in the fields, thwarting the plough, shading the sheep. I love the fogs that wreathe us all in milky veils, and the winds that moan and keen in the chimney piece at night. Even when the wrack line is crusted with salty ice and the ways through the woods crunch under my clogs, I drink the cold air in the low blue gleam that sparkles on the snow. Every inlet and outcrop of this place, I love.

It makes me ridiculously happy to say that this is one historical novel of old New England (and colonial America) which I can wholeheartedly recommend. It’s so common to find annoying, overdone stereotypes, and it was refreshing to read something so well done.

Also, if you’re looking for a field trip, Martha’s Vineyard is great, with beautiful scenery and fascinating historic sites. Just be warned that in summer, it’s crawling with people, and unfortunately that’s the only time some of the best stuff is open. But if you like to just ramble around without a crowd, and you don’t mind that some things are closed, the off-season is nice too.

Advertisements Share this: