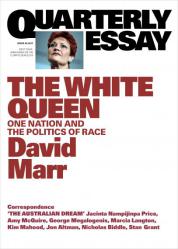

David Marr, The White Queen: One Nation and the politics of race (Quarterly Essay 64, 2017)

Pretty much ever since Pauline Hanson appeared on the political scene, there have been protests that the mainstream media pays too much attention to her. These tweets from March are recent examples:

I sympathise with the sentiments, but the ‘no-platform’ cry is surely wrong-headed. True, it’s painful to see precious media minutes taken up with, for example, crackpot comments on the Great Barrier Reef, but it’s the electoral system that has given Pauline Hanson a platform, and for the media to ignore her now would be derelict. Just recently, though, it’s hard not to feel we’re getting too much of a not-so-good thing: the ABC’s 4 Corners aired ‘Please Explain‘on 3 April; Richard Cooke’s ‘Alt-Wrong‘ is in the current issue of The Monthly; the summer issue of Overland gave us ‘No Pasarán!’ by Vashti Kenway (who as a teenager in 1996 threw eggs ‘with wild joy’ at Hansonites); and now here’s David Marr’s Quarterly Essay.

The essay obliquely acknowledges this dilemma. Marr writes, ‘Most Australians reject everything that Hanson stands for,’ but nevertheless ‘politics has been orbiting around One Nation since the day she returned to Canberra’.

The essay obliquely acknowledges this dilemma. Marr writes, ‘Most Australians reject everything that Hanson stands for,’ but nevertheless ‘politics has been orbiting around One Nation since the day she returned to Canberra’.

The essay gives a history of Ms Hanson’s political career since her stint on the Ipswich city council in the mid 1990s. It chronicles her turbulent relationship with the mainstream political right, including John Howard’s refusal to condemn her infamous ‘swamped by Asians’ maiden speech and his later opportunistic adoption of her policies (the section outlining Howard and Hanson’s trajectories is titled ‘Made for Each Other’). It reminds us of her brief sojourn in gaol and her release on a technicality (what she meant to do was illegal, but she hadn’t actually managed to do it). It takes us through her series of Svengalian advisers. It traces her progress, if that’s the word, from having ‘a folksy distaste for the blacks of Ipswich’ to being ‘an ideologue of race’ with ‘a conspiratorial mindset’.

Anyone who follows Australian politics will already know most of this, but it’s good to have it laid out plainly and without weaselly ‘balance’. There’s also joy to be had in the section ‘A Note on the Language’, which – as Raymond Williams’s Keywords did on a broader scale 40 years ago – examines the loaded meanings of words that have become prominent in the language of reactionary politics. Marr’s analysis isn’t as penetrating as Williams’s or that of the Keywords Project that continues his work, but it includes a number of gems, such as the entry on Free speech, which begins;

Free speech

Not about everything. Mainly Race. But it’s not free speech for pinging racists for being racists. That’s censorship or, indeed, persecution.

Pinging racism, as it happens, is at the heart of the essay. Where Marr’s previous QEs – on Kevin Rudd, Tony Abbott, George Pell, Bill Shorten – have been mainly character studies, this one is less interested in personality than in politics. It aims, as Marr says in a note on his sources, to put ‘a floor of fact under speculation about Hanson and her political appeal’. The fifteen-page section ‘Pauline’s People’ leans on the latest Australian Electoral Study numbers, drawing into the discussion ‘several professional pollsters who have conducted focus groups among resurgent One Nation voters’. One Nation voters in 2016:

- were almost entirely Australian-born (98 percent, with the Nationals coming closest at 91 percent)

- mostly described themselves as working class (66 percent, with the nationals again coming second at 46 percent, and Labor at 45 percent)

- compared to the general public, included half the proportion of university-educated people and twice that of people with trade qualifications

- thought things were ‘a little’ or ‘a lot’ worse for them than a year ago (68 percent, with Labor running second at 38 percent)

- believed politicians ‘usually look after themselves’ (a huge 85%, with the Greens a poor second at 51 percent)

- considered immigration ‘extremely important’ when deciding how to vote (82 percent), thought immigration should be cut ‘a lot’ (83 percent), believed migrants increase crime (79 percent) and take our jobs (67 percent)

- the kicker, ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’ with turnbacks of boats containing desperate people seeking asylum (a whopping 90 percent).

And 88 percent of them want the death penalty to be reintroduced.

‘Hanson’s people,’ writes Marr, ‘are not implacable conservatives.’ From marriage equality to euthanasia, they’re open to the small-l liberal agendas. They are generally in work and middling prosperous, though they’re ‘oddly gloomy abut their prospects’. They are overwhelmingly pissed off with government, against immigration and all for law and order. Of these, the hottest topic is immigration.

And as for racism:

Hanson’s people know she is talking race. They talk about it themselves in focus groups. Her candour on race is fundamental to their respect for her. They fear being branded racists if they complain about burqas and mosques and schools forbidding Christmas. She is not afraid. … ‘We’re not racist,’ they say. ‘We support Asians. We like them. We think they’ve done a lot here.’ But they don’t like Muslims. They don’t talk bombs and terrorist attacks in focus groups, though perhaps the threat of violence is somewhere in their minds. They talk a bit about lost jobs and a lot about people not fitting in. Not even trying to fit in. …

I’ve come to think it’s not much use asking if Australia is a racist country. It’s too broadbrush. The better question is: what role does race play in the politics of the country. This is not the politics of class or the politics of money, but the politics of difference. … The politics of race reassures white Australians unsure of their place in the heap that they’re on the only heap that matters.

Yet, as he says elsewhere, ‘neither Coalition nor Labor leader will bluntly call Hanson on race … the tactical impulse of the major parties is to flinch from naming her for what she is.’ As one of the most significant politicians of our times might say: Sad!

Added later: I forgot to say that one of the best things in this Quarterly Essay is the correspondence about the previous issue, Stan Grant’s Australian Dream. There are robust contributions from Aboriginal people – Alice Springs activist Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, Monthly contributor Amy McQuire, and the venerable Marcia Langton. George Megalogenis has intelligent things to say about Grant’s comparison of some Aboriginal experience with that of migrants. Kim Mahood brings her particular whitefella insights to bear. And Stan Grant uses his right of reply with robustness, civility and nuance.

Share this: