Foreshadowing sight gag.

Ira Levin’s Twisted Male Villains

Foreshadowing sight gag.

Ira Levin’s Twisted Male Villains

Soon after they are settled in Stepford, the novel’s protagonist, young mother Joanna Eberhart, awakes to her husband Walter masturbating in the bed next to her. He had just been initiated into the town’s “men’s association” and something he learned there that night excited him greatly–something he doesn’t share with his wife until she demands he include her, which he does reluctantly. It’s implied that his fantasy is much more titillating than his living, breathing wife who has her own needs. In the movie version, she finds him drinking in the den–shaken by the intelligence, on the verge of confiding with her, but something holds him back–the loyalty of men to themselves and to each other, a bond on which the very foundation of our world is based, not to mention armies and lucrative sports franchises. Not a bad thing, per se, but in Ira levin’s 1972 novel The Stepford Wives, it forms the basis of a deliciously diabolical plot, and plots are what Levin does best–Stephen King described him as “the Swiss watchmaker of suspense novels”, and every fiction writer should study him closely for not only his flawless structures, but for his clues about character, and archetypal truths. The masturbation scene was changed in the movie version for obvious reasons, but it keenly illustrates the key to Levin’s male villains: narcissists who selfishly and relentlessly pursue their own agendas as their clueless female victims suffer the consequences.

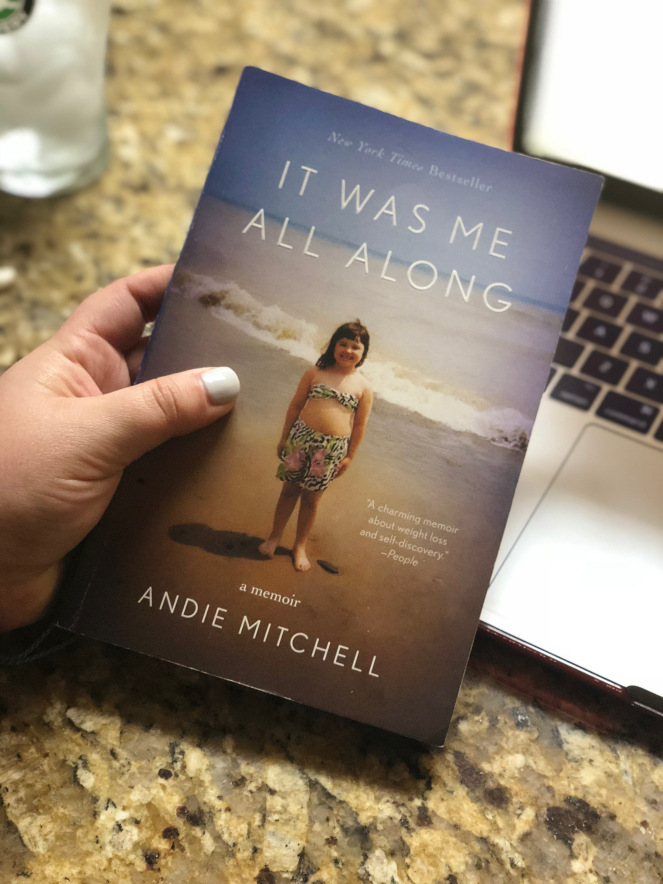

A Kiss Before Dying

Levin’s stunning debut novel, released when he was just twenty-four, introduces us to Bud Corliss, a handsome, charming college student who seduces not one, not two (as in the film versions), but three naive daughters of wealthy industrialist Leo Kingship. He seems more excited by the Kingship cooper mines than the beautiful young women who instantly fall under his spell, mere pawns in his endgame: to marry into a rich family and have a lucrative career–a psychopathic twist on An American Tragedy. We follow Bud early in the story when in WWII he guts a Japanese soldier with his bayonet and enjoys the surge of power he feels when the man pisses himself. That comes full circle later. Villains must pay, although in Levin’s world they mostly get away with it.

SPOILERS AHEAD: Rich girl Dorothy Kingship is “in trouble” (fifties parlance for pregnant). Bud, the seducer, blames her “passive neediness” for the mishap. Now the college kids have to get married outside her rich father’s blessings. Naive “Dotty “doesn’t mind if they live in a trailer park, but poor-boy Bud certainly does. When the abortion by pills doesn’t work, he breaks into the college chemistry lab and gives her more pills–this time filled with arsenic. In a rare display of disobedience, she doesn’t take them. The girl knows what she wants–Bud and baby–Daddy’s money be damned! Undeterred, he comes up with plan C, which leads to the famous toss off the roof scene that leaves the reader (and film viewer) on pins and needles even when you know it’s coming.

Whatever Bud wants.

Whatever Bud wants.

Nice guys and well-meaning patriarchs (the father has a change of heart) surround the doomed Kingship girls, but none of them possess the seductive power of the charming narcissist, the snake in the grass who will stop at nothing to get what he wants. The young women are helpless against Robert Wagner’s perfect pompadour and impressive bulge in tight trousers in the 1950’s film version. Less so, in the Matt Damon/Sean Young remake flop of 1991, although it’s still quite enjoyable for its camp qualities.

Rosemary’s Baby

Guy Woodhouse’s turn from self-centered, struggling actor to amoral servant of Satan happens off-stage. In Polanski’s film the moment of initiation is beautifully illustrated by a shot where Guy and elderly Satan worshipper, Roman Castevet, converse just outside of Rosemary’s point of view. All she sees (and we the viewer) is their cigarette smoke wafting through the stuffy living room: eerily resembling a puff of Satanic sulphur. When we see Guy again, he’s been “woke”. Seemingly without much inner conflict, the vainglorious actor offers his wife as a sacrifice to his success. Later, before she spits in his face (a rather satisfying moment), he is still defending his decision: ” Paramount’s within an inch of where we want ’em, and suddenly Universal’s interested too.” He seems perplexed that she doesn’t share his enthusiasm, after all she’s only been raped by the Devil and spawned his son. But oh well, he wipes the spit from his face and keeps serving drinks to the Satanic clan. The shark must keep moving in order to feed; the narcissist’s appetite holds no bounds. John Cassavetes is perfectly cast as Guy Woodhouse, handsome one moment, diabolical the next.

The secret world of men.

The secret world of men.

Homo interruptus.

Homo interruptus.

The men are behind it.

Walter Eberhard of The Stepford Wives is another husband who sells out his wife to the higher authority of men. Unlike Bud or Guy, Walter appears rather milquetoast and pussy-whipped by the feminist Joanna, until he meets the secret men’s association and grows a set. Then, he drunkenly tells her what to do and mocks her attempt at finding help with a kind, female therapist “Did she fix you?” Balding, schlubby Walter is frustrated with his free-thinking wife. Once she is changed to robot Joanna, he is finally free and happy. “The kids are better off too.”

Walter, happy at last.

Walter, happy at last.

The nebulous men’s association is lead by a sleaze named “Diz”, a former Disneyland engineer. “I like to watch women doing little domestic chores”, he muses while his male gaze burns into Joanna as she prepares coffee in the kitchen. She snaps back, “You came to the right town.” Braless in her hostess gown, Catherine Ross as Joanna beautifully embodies both the 1970’s new woman with the 1950’s traditionalist. She can intellectually spar with the best of them, but she’s no match for male loyalty and centuries worth of bonding. Her attempt to form a woman’s group fails miserably.

Never trust a man in a black turtleneck.

Never trust a man in a black turtleneck.

In the end the greatest strength she possesses, her maternal instinct, is used against her (as it is in all three novels). The men always win (except for Bud). I sense that young Levin may have made Bud pay because that was what was expected in the 1950’s. He could have very easily gotten away with it.

The failed 2004 remake of The Stepford Wives turned it into a comedy and the term has long been a moniker for rich, vapidly beautiful housewives, but the true essence of the story is one of horror, and it still rings true today. In the story’s climax, Joanna is replaced by her new and improved android version as Diz watches–excitedly getting off as the robot of his fantasy replaces the real woman with her complaints and needs. “Why?” Joanna asks. His answer, “Because we can.”

The men have this under control.

Advertisements

Share this:

The men have this under control.

Advertisements

Share this: