The legacy and concept of “revolution” resonated with the Surrealists. This is best exemplified by the more archetypal journals associated with the Surrealist movement, such as La Révolution Surréaliste (1924-1929) or La Surréalisme au service de la révolution (1930-33).

Emerging in Paris during the interwar period, the Surrealist revolution responded to a set of conditions, including economic decline, inequality, xenophobia and populism during a period punctuated by political unrest. Their revolutionary agenda was concerned with both economic and existential liberation and was expressed through an intersection of innovative cultural production and political activism. The Surrealists of the entre guerre were emphatically radical politically, having had an uneasy affiliation with the French Communist Party from around 1927. Much has been discussed about Surrealism’s internal schisms and the movement’s relationship to political institutions. Much less, however, has been noted about the way Surrealism presented itself within the historical tradition of revolution in France[1] Far from a unified movement, Surrealism fractured around the metaphor of revolution. Decapitation, as a symbol of revolutionary rupture, death, violence, anarchy, and history, became contested—such contestation reveals the fracture between “low” and “high” Surrealism.

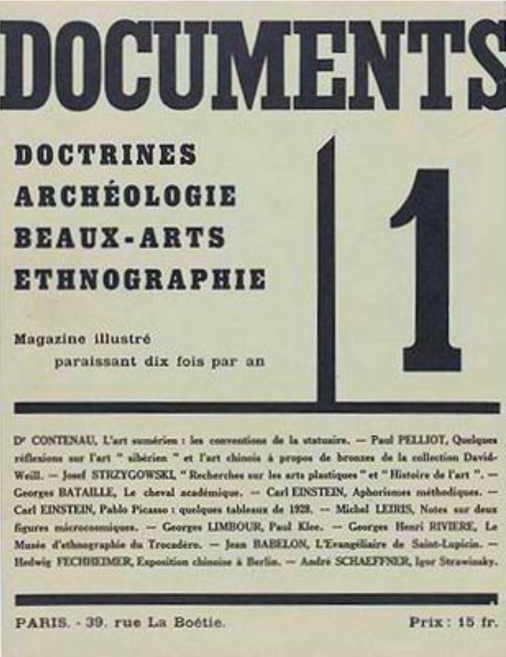

The 15 issues of the idiosyncratic and lesser-studied Surrealist publication, Documents demonstrate an intersection of ideas and tendencies considered to be some of the most disruptive in modern art and critical thought. Edited principally by heterodox avant-gardist Georges Bataille, the publication (1929-30) was often radical and subversive, actively going against the academic conventions presented in reviews similar in content — reviews in other fine arts/academic publications like Gazette des Beaux Arts, Variétés or Jazz — while violent juxtapositions of images and text aimed towards an anarchic destruction of all hierarchies of art, politics, and morality.

The 15 issues of the idiosyncratic and lesser-studied Surrealist publication, Documents demonstrate an intersection of ideas and tendencies considered to be some of the most disruptive in modern art and critical thought. Edited principally by heterodox avant-gardist Georges Bataille, the publication (1929-30) was often radical and subversive, actively going against the academic conventions presented in reviews similar in content — reviews in other fine arts/academic publications like Gazette des Beaux Arts, Variétés or Jazz — while violent juxtapositions of images and text aimed towards an anarchic destruction of all hierarchies of art, politics, and morality.

Members of what I would term the “low” faction of Surrealists associated with Georges Bataille and Documents considered the side of Surrealism associated with the “Surrealist Pope” André Breton to be idealist and infected with a pathological Icarian complex. “High” Surrealism uttered insolent provocations while craving punishment, thus reinforcing the status quo they superficially appeared to reject.[2] By isolating Documents and considering the visual language at play, it becomes clear that this “Low” Surrealism was very much appropriating the French Revolutionary tradition to communicate a position distinct from the Surrealist movement at large in which paradox, sacrifice and violence and the play between sacred and profane are intimately bound with community and renewal.

This rejection of orthodox Surrealism was acted out in a symbolic regicide in Un Cadavre in January 1930—a parody of a 1924 Surrealist publication of the same name. The 1930 version of the pamphlet features a series of texts written by the exiled Surrealists and amounts to a collective rejection of Breton’s leadership and his idealism. On the cover Breton, in a photomontage taken by Jacques-André Boiffard from a page of La Révolution surréaliste, is rendered corpse. His face appears in the centre on the cover, framed by text with his eyes closed and his head crowned with thorns.

A similar use of the crown of thorns can be found in the 1789 engraving, A un peuple libre, which features the iconoclastic dethroning of a bust depicting the king, over which an angel holds a halo in place, affirming the king’s divine right. Underneath, the people are installing a portrait of Jean Sylvian Bailly, the first mayor of Paris under the Revolution and first signatory of the Tennis Court Oath. Bailly is being crowned with a crown of thorns, indicating his authority is both radical and democratically sanctioned in opposition to the sacred authority of the king.

Jean B Dambrun, Jean Duplessi- Bertaux, Jean-Michel Moreau. A un peuple libre. Engraving, 1789. 24 x 20 cm

Jean B Dambrun, Jean Duplessi- Bertaux, Jean-Michel Moreau. A un peuple libre. Engraving, 1789. 24 x 20 cm

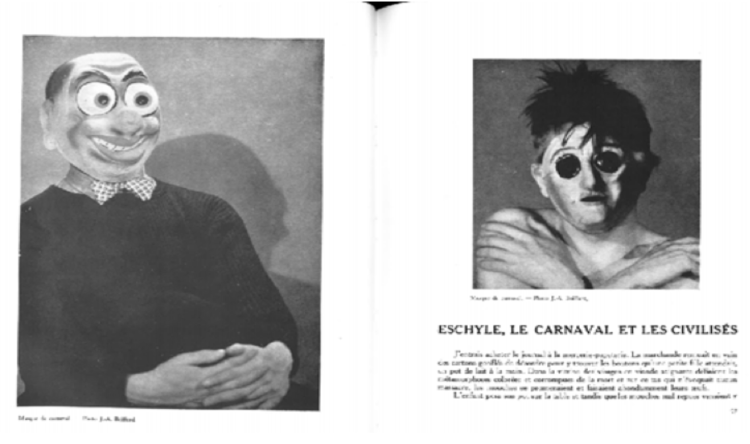

The reader of Documents is consistently confronted by disembodied heads—tribal and carnival masks, acephalic statues, trophy skulls—representations by modern painters, sculptors and photographers which emphasize and allude to the head and headlessness. The final image of the last issue of 1929 is a full-page photograph of an Ekoi mask from the British Museum accompanying an article by Carl Einstein. Another full page Bapundi mask appears at the end of No. 1 (1930) and it is in No. 2 (1930) that the head motif begins to appear more frequently, more aggressively, with greater dynamism and a polemical quality. I would suggest that this motif is part of Documents’ rhetoric of revolution and consciously refers to the sacrificial rebirth of France via the French Revolution and the Terror.

Spread from Documents No. 2 (1930) 96-98. Featuring two photographs entitled Carnival Mask by Jacques-André Boiffard.

Spread from Documents No. 2 (1930) 96-98. Featuring two photographs entitled Carnival Mask by Jacques-André Boiffard.

Decapitation and the disembodied head function as positive motifs in the French revolutionary imaginary, symbolizing the destruction of the corrupt, despotic monarchy and the birth of the French citizen within the new, democratic Republic. As Jesse Goldhammer has discussed, sacrifice played a foundational role in both the birth and death of French monarchy; the symbolic sacrificial Catholic ritual of baptism throned Clovis I with sacred power while the decapitation of Louis XIV by the French Revolutionaries in 1792 transferred the king’s sacred authority to the people.[3] Article 3 of the 1793 Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen expressed the idea of the Republic as a body of French citizens unifying in a voluntary community; this conception of the nation as a “living fraternity” bolstered a republican patriotism with modern France as the sacred embodiment of secular citizenship and democracy founded in the sacrifice and violent overthrowing of the ancien régime by the guillotine, Le Rasoir National. Decapitation is presented within Documents as symbol of “Low” Surrealism’s revolutionary intentions; severing the body politic from the sovereign head; the political, rational and social confines of bourgeois civilization.[4] The language of sacrifice is invoked to mark the destruction of the old regime and the transfer of power to the citizens.

Hailey Maxwell is a doctoral student in History of Art at the University of Glasgow, where she also graduated from the department’s MLitt programme “Art, Politics, Transgression: 20th Century Avant-Gardes.” She is interested in the interwar avant-garde circle around Surrealism and Georges Bataille with a focus on ideas of aestheticized politics and community. You can tweet her @_acephale.

Title image: Frontispiece Un Cadavre pamphlet (ed.) Georges Bataille. Paris. 15th January 1930.Photomontage portrait of André Breton by Jacques¬André Boiffard.

Endnotes

[1] As the threat of fascism grew, ‘High’ and ‘Low’ factions of Surrealism unified to form the short-lived activist group Contre Attaque.

[2] Georges Bataille. “The Old Mole and the Prefix Sur- in the Words Surhomme and Sur-Realism” in Visions of Excess: Selected Writings 1927-1939 .ed. Allan Stoekl trans. Allan Stoekl with Carl R. Lovitt and Donald M. Leslie Jr. Minneapolis : University of Minnesota Press. 1986. 32-45

The editorial board of the magazine included : Georges-Henri Rivière; the assistant director of the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro, and ethnologist Paul Rivet who in 1925 had together with Marcel Mauss, Lucien Lévy-Bruhl established the Institut d’Ethnologie in Paris. See Connor Joyce, Carl Einstein in Documents and His Collaboration with Georges Bataille. (Xlibris Corp : USA. 2002). 17-32

[3] Jesse Goldhammer. The Headless Republic: Sacrificial Violence in Modern French Thought.(Ithaca ; London : Cornell University Press, 2005).

[4] My research is concerned with Documents and two related associations – the Collége de sociologie and Acéphale – all of which I would suggest display a ‘low’ surrealist ideology.

Further Reading

Ades, Dawn; Simon Baker, Fiona Bradley et al. ed. Undercover Surrealism: Georges Bataille and Documents. London : Hayward Gallery 2006. Published in conjunction with the exhibition “Undercover Surrealism: Picasso, Miro, Masson and the Vision of Georges Bataille”” at the Hayward Gallery, London.

Bataille, Georges. (ed)., Documents Vol 1&2 Fifteen issues. 1929-1930. Facsimile edition Paris : Jean Michel Place. 1991-92.

Clifford, James. “On Ethnographic Surrealism” Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 23: (October 1981), 539-564.

Share this: