The author of this essay is Dom Karl Wallner, O. Cis., Rector of the Pontifical University of Heiligenkreuz (AU) and national director of Missio for Austria. The following passages are extracts from his address at the session of the International Academy held 31st August 2016 at Aigen and translated into English by Canticum Salomonis.

(See the German original and French translation.)

The last few decades have brought a stark alteration of Catholic cult, liturgy, art, and architecture that many perceive as a break and a rupture, or even as an outright destruction of the former dignity and sacrality. In the long theological debates of the 1970s, “desacralisation” was treated as an imperative for the modernisation of the Church.

Along with desacralisation inside the Church there was another phenomenon, which I was able to experience personally in my encounters with the profane world of show business: a form of sacralisation of the profane, a ritualisation of the banal, the promotion of non-religious objects to the level of cult objects. From the backstage of the show to which I had been invited, I could observe how the show was designed down the last detail as a sort of dramaturgy, so that the viewer in front of the television participated in a kind of “Pontifical Mass of Entertainment.”

Several years ago, after celebrating a vigil service with a youth group, I had an experience that struck me profoundly and became the key to understanding.

For the past 20 years at Heiligenkreuz, we have organised prayer retreats for young people between the ages of 15 and 28. Since the majority of young people that age suffer a severe lack of enculturation in everything related to Catholicism, and must still learn how to pray and adore, these vigils represent a real challenge. That is why we could not even imagine celebrating a Mass with them: we must first render these young capable of receiving the Eucharistic mystery. First and foremost they need to have a personal relation to Jesus Christ. In that regard, the Catholic liturgy offers a range of possibilities, a whole sacred repertoire that is able to create an ambiance that permits the young people to open their hearts so that they may be touched by the presence of God.

Concretely, this is what happens at our monastery: the light is turned down in the nave of the church; we do lots of singing, especially hymns of praise; the entrance procession begins from the medieval shadow of the cloister, to the light of candles, reciting a decade of the rosary; the Holy Sacrament in the monstrance is brightly illuminated so as to constitute a central point, majestic and brilliant, drawing the gaze of about 300 youth praying and adoring on their knees. The bells ring at full force as the priest blesses the crowd. The celebrant wears a solemn veil. The acolytes arrange themselves in perfect order. In a word, we use all the resources the Catholic liturgy offers us from the point of view of dramaturgy.

And of course, we use lots of incense…

Sight, hearing, the chant, the smell of incense, the gestures and postures…etc. become concrete instruments that encourage the soul to open up. We notice that the incense does more than please the sense of smell. It also gives visibility to space: as it rises it produces a sensation of height, elevation, well-being, and solemnity.

It is in this context that I had the experience I mentioned. At the end of the Vigil, one of the youth who completely unformed came to see me. He was profoundly moved, radiant and excited. He told me: “Father Karl, your vigils are super cool, so modern! You even use the fog machines like they do in the disco!”

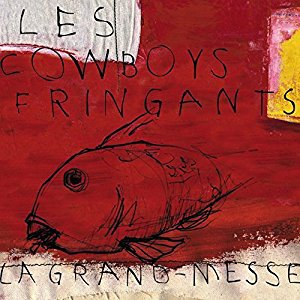

I think that today we are witnessing the beginnings of a return to a previous situation, and this is most evident in the youth: from a desacralisation of the Catholic world toward a certain re-sacralisation, in the sense of a renewed understanding of terms like “cult” or “celebration” among the younger generations. Among young people, there is no greater praise for an event, concert, or music group as when it can be said to have reached “cult status.” [French: In the same way, a particularly successful concert is called a “great-mass” (grand-messe).] The same holds true for the word “celebration.” Often decried before and still always avoided in ecclesiastical circles, this term has been rediscovered in a quasi-euphoric way in the profane world. It’s because we love moments of solemnity. The business world thrives on flashy “celebrations” full of glamour.

When one loves the liturgy of the Church and considers it the very substance of his life, like here at Heiligenkreuz where I have had the honor to hold the duty of MC for 21 years, one is often astonished to realize that “the sons of the world are often more wise than the sons of light.” The dignity, majesty, solemnity, the sense of ritual, all those things that were normal in the Church during past centuries, but have been gravely neglected since the 1960s in a movement of secularisation that was complete unprecedented, have now been “discovered” in the profane world, and integrated into this context as a great novelty.

I’ve already mentioned those big televised shows in which I participated, sometimes willingly and sometimes by compulsion, and that I experienced them as pseudo-liturgical productions. These “entertainment liturgies” have as their goal to create feelings of tension, emotion, well-being and amusement: i.e. an earthly happiness composed of dramatised emotions. And they spare no expense! The majesty of the place, reinforced by the movement of the camera, the presence of a “great pontiff” well known by all, the promise of substantial profit and media recognition… The presenter-star is given a form of veneration that we once reserved for the priest at the altar, for in the priest we honored the great majesty of Christ. In the sacralised profane, this veneration has devolved into a drab personality cult and the worship of “stars” [Starrummel; starisation].

The sacred is an experience of a separation, a contrast. It involves a subjective notion, a sentiment, a fundamental constant of human psychology. Who has not felt a surge of respect and emotion during a grand and solemn moment of music, in a place where the architecture has the qualities of height and symmetry? Who has not felt awe and emotion when participating in an unaccustomed scripted ritual, a feeling of unity and cooperation in the midst of a large crowd? The feeling gives you goosebumps!

Lars Olaf Nathan Soderblom, a Swedish historian of religion, defined the sacred in 1913 as “the notion determining all religion; it is more important even than the notion of divinity.”

The experience of the sacred is more fundamental than the notion of the divine. This means that religiosity is based in the first place on letting oneself be touched by the existence of something that transcends the every-day, through a sort of purity and majesty, something that compels respect, something unexpected. It is only based on this experience that a man seeks the origin of this sentiment in God.

Historically speaking, the first acts of man of a religious connotation were not addressed to a personal god. They were rather the reflection of a sentiment; a feeling of being affected, touched, by a kind of majesty, by something other, by what is beyond the frontiers, by a “sacrum.” This fundamental constant of religious sentiment had to await Christianity to be purified and magnified. Indeed, amidst this fascination, suddenly a personal God is revealed, a person who, in Jesus Christ, would even have a concrete, historical existence among men, and who through the Holy Spirit would inhabit the hearts of men.

We repeat: the necessity of being affected by what one feels is “sacred,” even to the point that it makes our hair stand on end, is fundamental for man: for man is predestined for the sacred.

This is confirmed in a negative way: since the 1980s we have witnessed a dramatic decline in the Christian faith, and more generally of the ability to establish a relationship with a personal God. A study dating from 2015 (“Shell-Jugendstudie”: a study of 2500 youths in Germany between 12 and 25, from all backgrounds)—conducted not by theologians using hued glasses, but by serious sociologists—characterises young German Christians as “baptised pagans.” This study, which shows a very realistic picture of the situation, is not encouraging: only 35% of Christians interviewed said they believed in a personal God; only 39% thought that faith in God has an influence on their life choices.

Even if, according to the terms of the study, there has been found an “almost complete rupture with the Christian faith,” this does not signal the rise of atheism pure and simple. What has changed is the object of the faith, which is no longer God, but all sorts of other things: vacations, liberty, autonomy, the traditions of feasts around Christmas, the horoscope, a car, a football club, etc. People have not stopped to act in religious ways, but they no longer believe in Jesus Christ, and have no idea what a sacrament of the Church is. In place of a personal relationship with Jesus Christ, such as might appear in Eucharistic Adoration or meditation on the history of salvation through the mysteries of the rosary, one now finds other exercises of religious piety taken from eastern meditative techniques, occult practices, and post-modern ideas. This practices are already widespread in the present culture and enjoy a very popular image.

Here I would like to call upon an example of profane canonisation in the person of Lady Diana. After the death of the Princess of Wales in Paris on the 31st of August, at age 36, her passing triggered a phenomenon the world over that might be called “euphoric grief.” The fact that the personality involved was very famous, very engaged in helping marginalised and socially excluded groups, led to a wave of compassion and solidarity to a degree that had never been witnessed before. The extent of mourning evoked had the effect of “raising Diana to the skies.” At that moment who would have dared to mention, even in a whisper, that the princess might have been responsible for the failure of her marriage? Diana became a myth, an idol of goodness and pure human compassion. This “canonisation” reached its acme a few days later when we learned about the death of Mother Teresa of Calcutta, this time a true saint of the Church. The crowds received this event as a confirmation and consolation. They recalled the suggestive photos showing the two side by side: two saints in full agreement. As if the radiance of Lady Diana’s face transfigured the wrinkled countenance of Mother Teresa. As if the Christian faith of Mother Teresa transfigured the black marks in the life of the unfortunate princess. As for Lady Diana, we might further remark that the palace where her tomb is located has become almost a place of pilgrimage, where one can find many features similar to places of Christian pilgrimage, though especially the less appealing ones.

It seems that any profane action is susceptible to being sacralised, and history abounds with examples of such abusive cults rendered to persons. Consider the dictators or those responsible for genocide. One certainly thinks of the adulation that was offered to Hitler, or the long files standing at attention before the mausoleum of Lenin, or more recently, to the grotesque behavior of the masses toward the North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un.

Thus we must be very prudent. If we do not cultivate the sacred and the dignified in our churches, if we forget the “tremendum” and “fascinosum,” then we can expect that human psychology will go looking elsewhere to fill the need to tremble before something majestic. If we degrade our liturgical ceremonies to the level of simple mundane ceremonies, if we banalise them, we should not be surprised to see people going elsewhere to satisfy their innate desire for sacred places, sacred symbols, sacred texts, and persons to venerate.

I’d like to share a personal memory. Some weeks ago, I happened to find myself by chance in possession of a ticket for the inauguration of the new stadium of Vienna-Hütteldorf, the Rapid-Stadion. During my whole life I have never attended a football game. I was alone, and I was seized by an anxiety about how I should enjoy the event. I was tempted not to go at all. But I intentionally made myself have these feelings, comparing myself to someone confronted by the idea of entering a church for the first time to see a Mass. I wanted to feel the genuine fear that people often feel before doing something they are not used to, of encountering customs and attitudes they’ve never experienced, and the fear of being noticed.

For me watching the match was also a sort of expiation. My father, now deceased, was a passionate fan of the Rapid team, and in some way I owed it to him to go there in his memory.

It was incredible. What I experienced there was a fascinating profane liturgy. The match was a friendly encounter against Chelsea, but the match itself it was nothing but a pretext. A genuine liturgy took place, with chants, ritual applause, coordinated movements of the crowd, and waving the club’s green emblem. But what left the strongest impression on me was an action that might have been inspired by the liturgical epiclesis. In the middle of the 75th minute, they began to call on the “15-minute Rapid.” Thanks to Wikipedia I knew that this tradition had existed since 1910. What was it? Everyone stood up, held their hands in front of them palms down, like the priest when he calls down the Holy Spirit on the bread and wine at the moment of consecration. At that moment a humming, a rhythmic droning arose in the seats where the 28,000 spectators were packed. It got louder until the hands began a trembling motion. I thought right then: “Come, holy spirit of football!” After the tension was brusquely relieved, loud cheering swept through the stadium.

During the match the idea came to me, that it is a shame the Church of Austria doesn’t organise at least once a year a great public festival in a profane place. A sort of testimony to the presence of Christians outside the churches and sacristies. The Evangelical churches and the Jehovah’s Witnesses do this type of thing regularly. Closer to home, the origin of the Corpus Christi processions is the desire to manifest our veneration for the Holy Sacrament by carrying it through the city streets, across fields, and into all the places of our daily life.

Though I have no pretensions in this address of offering an exhaustive argument, I think I can affirm that there exists a correlation between “a profanation of the sacred” and “a sacralisation of the profane.” Opened to transcendence, man needs a “tremendum” and “fascinosum.” If religion no longer gives him thrills, he will begin to sacralise his profane environment, to idolise anything and everything.

Some strong words of the Cure d’Ars come to mind: “Leave a parish without a priest for twenty years, and they will start worshipping the animals.” And I’ll venture to follow up: “Deprive man of respect for sacred things, such as the liturgy is meant to express, strip down the sacred service offered to the unfathomable divinity till it is a simple worship rendered to man, and you shall see the faithful flee their priests and turn to the druids and shamans, and worship the stars and animals as their deities.”

But aren’t we something responsible for what is happening?

Profanation begins when we ourselves no longer respect holy things. Everyone knows that you take your shoes off when entering a mosque and that silence must be respected there, or even that you must wear a kippa in a synagogue. But a Catholic church is no longer respected more than some museum! It all begins when we no longer think it necessary to genuflect before the Blessed Sacrament, which is not an abstract notion as in other religions, but a very concrete sacramental reality. When we prattle on in church like so many pagans. One has the experienced visiting the Cathedral of St. Stephen in Vienna and then the city’s history museum: there, you find the sacred profaned, here the profane sacralised.

Someone will probably say to me, “Yes, grave errors have been committed in our Church. The spirit of the times has pushed us toward a certain desacralisation and so favored the birth of new pagan religious movements.” But once more I repeat a truism I have already cited: when the faith we have received from God is shown the door, superstition enters through the window.

I fear that the demythologised theology, the desacralised art and liturgy we have endured for some decades, are often self-defeating, as it were. If we are no longer capable, by means of sacred art and liturgy, of transmitting the reality of the advent of God into the life of man, then he will make a substitute for himself. If we no longer transmit to man that sacred gift that permits him to encounter God who in Jesus Christ has been made so close and so majestic, then man will find something else to satisfy him. And it seems that nothing profane is able to escape from his desire for sacrality: ideologies and nations, Führers and stars, T.V. shows and rituals … everything that happens seems charged with sacrality.

And now? What shall happen? Something different, in any case! There is no future in the Church for desacralised rites: they are already passé.

The young generation of seminarians surprises us by their taste for solemnity. They appreciate the idea of “celebration,” they are fascinated by the aesthetics of ritual. They want to know the liturgical norms precisely and follow them. And this is definitely not a step backward, toward pre-conciliar ritualism, as some have prophesied, thus showing that they do not know how to recognise the signs of the times.

The faithful young, born long after the end of the pre-conciliar era—doubtlessly guided by the Holy Spirit—is set to vindicate every liberty for sacrality, which has proven to be constitutive of the very essence of Christianity.

These youth are exempt from every ideology, opposite to those who lived through ’68. They set great value in sacrality because they have instinctively realised that it is thanks to it that they have the concrete ability to approach the Holy God-made-man: thanks to a majestic liturgy, to sacred music, to hymns of praise, to trustworthy rites, an architecture open to heaven and an art that speaks a language of transcendence.

—Deo gratias!—

*Marginalia Aelredi*

(in sup. sinistra, eleganti stylo)

Frater nostri ordinis, vir probatus, dicendi peritus.

(notae)

Hoc “show-biz” ex “turris Babylonis” derivatus?

…

Canones ludis publicis monachos omnimodo prohibere; reverendus frater monendus.

…

Testes Jehovae = apud Paulum ἰουδαϊζόντες? Pertinaces!

…

Vivitur ut filii Israel inter paganos. Templa paganorum cur non destructa?