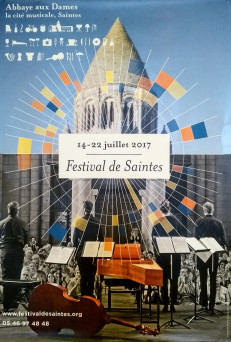

Festival de Saintes

Abbaye aux Dames: la cité musicale, Saintes

14-22 July 2017

The Abbaye aux Dames was founded in 1047 by the Count of Anjou as a Benedictine abbey for women, usually of aristocratic origin. Around 1120, the Abbey church was altered and the spectacularly carved west end facade and bel l tower were added. Internally, the Romanesque triple-aisled basilica was altered, rather inelegantly, by inserting two enormous domed cupolas into the original external walls, resulting in a bit of an architectural mess. After two major fires in the 17th century (which destroyed the cupolas), the church was restored, and impressive new convent buildings were added, with cells for 45 nuns. During the Revolution, the Abbey first became a prison (1792), and then a barracks (1808). In the 1920s, the Abbey complex was purchased by the town of Saintes. In the 1970s, restoration of the monastic

l tower were added. Internally, the Romanesque triple-aisled basilica was altered, rather inelegantly, by inserting two enormous domed cupolas into the original external walls, resulting in a bit of an architectural mess. After two major fires in the 17th century (which destroyed the cupolas), the church was restored, and impressive new convent buildings were added, with cells for 45 nuns. During the Revolution, the Abbey first became a prison (1792), and then a barracks (1808). In the 1920s, the Abbey complex was purchased by the town of Saintes. In the 1970s, restoration of the monastic  buildings (abandoned since the war) was started and, in 1972, an annual Festival of Ancient Music was created, later becoming the Festival de Saintes. In 1988 the Abbey was launched as a cultural centre by President François Mitterrand, and in 2013 it became la cité musicale, housing a Conservatoire of Music and a range of year-round musical activities, including many for young people. The former nun’s cells now sleep visitors and guests of the Festival.

buildings (abandoned since the war) was started and, in 1972, an annual Festival of Ancient Music was created, later becoming the Festival de Saintes. In 1988 the Abbey was launched as a cultural centre by President François Mitterrand, and in 2013 it became la cité musicale, housing a Conservatoire of Music and a range of year-round musical activities, including many for young people. The former nun’s cells now sleep visitors and guests of the Festival.

This year’s Festival de Saintes lasted from 14 to 22 July, although I was only able to attend from Sunday 16 to Tuesday 18 July, a period that included many of the ‘early music’ events of the Festival. My first concert (Sunday 14 July) was given by the Basel-based vocal ensemble, Voces Suaves directed by baritone Tobias Wicky. They formed in 2012 from the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis and from 2014 to 2016 were part of eeemerging, the Emerging European Ensembles Project, a large-scale European cooperation project promoting the emergence of new talent in early music. Their programme featured Monteverdi madrigals under the title of T’amo, mia vita. I liked the way that they started their concert. Instead of a formal entry of musicians, the seven singers and theorbo player gradually arrived and sat on the front of the stage, where they waited quietly while the audience settled down. They started their first madrigal, Ecco mormorar l’onde, from that position. There followed a well planned sequence of 12 madrigals drawn from all eight of Monteverdi’s books, with Voces Suaves catching the varied moods perfectly. In the Lamento della Nifa, the i

This year’s Festival de Saintes lasted from 14 to 22 July, although I was only able to attend from Sunday 16 to Tuesday 18 July, a period that included many of the ‘early music’ events of the Festival. My first concert (Sunday 14 July) was given by the Basel-based vocal ensemble, Voces Suaves directed by baritone Tobias Wicky. They formed in 2012 from the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis and from 2014 to 2016 were part of eeemerging, the Emerging European Ensembles Project, a large-scale European cooperation project promoting the emergence of new talent in early music. Their programme featured Monteverdi madrigals under the title of T’amo, mia vita. I liked the way that they started their concert. Instead of a formal entry of musicians, the seven singers and theorbo player gradually arrived and sat on the front of the stage, where they waited quietly while the audience settled down. They started their first madrigal, Ecco mormorar l’onde, from that position. There followed a well planned sequence of 12 madrigals drawn from all eight of Monteverdi’s books, with Voces Suaves catching the varied moods perfectly. In the Lamento della Nifa, the i mpressive soprano soloist (Lia Andres, I think) starting singing from the back of the Abbey, slowly progressing down the central aisle. They lightened the rather intense mood towards the end, following T’amo, mia vita by segueing Io mi son giovinetta into the concluding Ohimé, se tanto amate.

mpressive soprano soloist (Lia Andres, I think) starting singing from the back of the Abbey, slowly progressing down the central aisle. They lightened the rather intense mood towards the end, following T’amo, mia vita by segueing Io mi son giovinetta into the concluding Ohimé, se tanto amate.

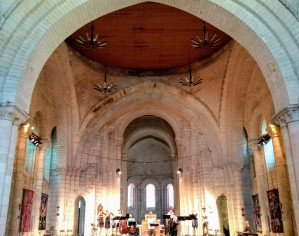

One particularly notable feature of the Abbaye aux Dames is the surprisingly good acoustics. At first sight, the vast church interior seemed to be entirely unsuitable for the clarity of sound that most music requires. However, after the 17th century destruction of the two vast cupolas that used to cover the whole of th e nave, two enormous circular wooden ceilings were used to fill the circular gaps. These act as giant sound absorbers and improvers, reducing the reverberation time to something well suited for Baroque music, as well as retaining sufficient bloom for Renaissance music. The sound of a single voice, or a lute solo, can carry clearly to the back of the Abbey church, while consort music is allowed to blend well without becoming muddy. For the largest audiences, the original Romanesque choir, behind the stage and transept arches, are used for seating, with television monitors providing a view of the front of the performers.

e nave, two enormous circular wooden ceilings were used to fill the circular gaps. These act as giant sound absorbers and improvers, reducing the reverberation time to something well suited for Baroque music, as well as retaining sufficient bloom for Renaissance music. The sound of a single voice, or a lute solo, can carry clearly to the back of the Abbey church, while consort music is allowed to blend well without becoming muddy. For the largest audiences, the original Romanesque choir, behind the stage and transept arches, are used for seating, with television monitors providing a view of the front of the performers.

A big test of the acoustics came with the late Sunday evening recital of Bach’s Goldberg Variations played by Benjamin Alard on a harpsichord built by Anthony Sidey in 1983. Demonstrating a masterly technique and musical authority, Alard judged the style of each variation  perfectly. As with the previous concert, I liked the way that he started, quietly sitting and waiting for the audience to subside into a rather long-awaited silence. Alard’s use of subtle rhetoric and shading of notes kept the focus on the music, as did his varying of the gaps between variations. I am never quite sure of the convention of repeating the opening of a set of variations at the end. It often feels that it breaks the sense of a journey forward from the original theme to the climax of the final variation, in Bach’s case, the complexly jovial Quodlibet. But it somehow seemed right on this occasion, not least to return the Abbey church to comparative calm before the audience decamped for late-night jazz in the Abbey courtyard.

perfectly. As with the previous concert, I liked the way that he started, quietly sitting and waiting for the audience to subside into a rather long-awaited silence. Alard’s use of subtle rhetoric and shading of notes kept the focus on the music, as did his varying of the gaps between variations. I am never quite sure of the convention of repeating the opening of a set of variations at the end. It often feels that it breaks the sense of a journey forward from the original theme to the climax of the final variation, in Bach’s case, the complexly jovial Quodlibet. But it somehow seemed right on this occasion, not least to return the Abbey church to comparative calm before the audience decamped for late-night jazz in the Abbey courtyard.

The following day’s three concerts covered the extremes of the concert-giving world, with two very young performers, a relatively new but very professional group, and the giants of the French music scene, Les Arts Florissants. We started with the middle category with the lunchtime concert of three Bach cantatas (BWV 146, 108 & 103) given by the Swiss group, Gli Angeli Genèvre. They started with BWV 146 Wir müssen durch viel Trübsal, with its extraordinary opening Sinfonia, a one  movement organ concerto of considerable virtuosity, here played with stylish panache by Francis Jacob on a powerful, if rather shrill little chamber organ. Bach follows this flamboyant opening with the measured tread of an expansive choral movement, again with the organ as soloist, its melodic line floating above the voices. Both these movements are based on an earlier harpsichord concerto which, in turn, was seems to have been based on an even earlier violin concerto. In this, and the two following cantatas, the four soloists (Aleksandra Lewandowska, Alex Potter, Nicholas Mulroy, standing in at short notice, and Stephan MacLeod, managing to switch from singing to conducting with apparent ease) and four supporting singers of Gli Angeli Genèvre sang with superb conviction and style, supported by an excellent group of instrumentalists, led by Eva Saladin, violin. For their encore, they repeated the opening Sinfonia.

movement organ concerto of considerable virtuosity, here played with stylish panache by Francis Jacob on a powerful, if rather shrill little chamber organ. Bach follows this flamboyant opening with the measured tread of an expansive choral movement, again with the organ as soloist, its melodic line floating above the voices. Both these movements are based on an earlier harpsichord concerto which, in turn, was seems to have been based on an even earlier violin concerto. In this, and the two following cantatas, the four soloists (Aleksandra Lewandowska, Alex Potter, Nicholas Mulroy, standing in at short notice, and Stephan MacLeod, managing to switch from singing to conducting with apparent ease) and four supporting singers of Gli Angeli Genèvre sang with superb conviction and style, supported by an excellent group of instrumentalists, led by Eva Saladin, violin. For their encore, they repeated the opening Sinfonia.

On the fringes of the main festival events were a series of concerts by four groups of young musicians (Place aux jeunes musiciens) touring round four different venues in and around Saintes. I heard the clarinet duo The Küffner  Gals perform in the entrance hall of the Saintes Palais de Justice, with a programme of music from the late 18th and early 19th century as the clarinet found its musical footing. Musically and technically they were very accomplished, although they could perhaps have allowed themselves a little more give and take with the pulse and phrasing of the music, which was moving from the Classical into the Romantic era. Like most young performers, they could also do with learning how to acknowledge applause before getting ready for their next piece. Some of the early pieces were rather too much solo and accompaniment, but the last two, by Vanderhagen and Crusell, were more equally balanced between the two clarinets and more impressive, albeit with rather a lot of running after each other in thirds.

Gals perform in the entrance hall of the Saintes Palais de Justice, with a programme of music from the late 18th and early 19th century as the clarinet found its musical footing. Musically and technically they were very accomplished, although they could perhaps have allowed themselves a little more give and take with the pulse and phrasing of the music, which was moving from the Classical into the Romantic era. Like most young performers, they could also do with learning how to acknowledge applause before getting ready for their next piece. Some of the early pieces were rather too much solo and accompaniment, but the last two, by Vanderhagen and Crusell, were more equally balanced between the two clarinets and more impressive, albeit with rather a lot of running after each other in thirds.

The evening concert in the Abbaye aux Dames was given by Les Arts Florissants and their programme Chants Joyeux du temps de Pâques, a sequence of Mark-Antoine Charpentier’s sacred works forming of a meditation on the story of the passion and resurrection. After the opening dramatic motet, Nuptiae Sacrae, the passion was represented by the slowly unfolding texture of Transfige dulcissime Jesu (acting as the Elevation section of a Mass), and the depiction of the discussion between  Jesus and Peter in La Reniement de St Pierre. The Stabat Mater pour des religieuses (a particularly appropriate piece for the Abbeye des Dames) and the hymn O crus spec unica represented the crucifixion. The Dialogues inters Magdalenam et Jesum depicted the encounter between Mary-Magdalene and Jesus before the joyous concluding Chants joyeux du temps de Pâques. The 19-strong chorus was generally good, but there was rather too much vibrato from some of the sopranos. Most singers had solo spots, some more than other, with some particularly good low female alto voices (bas-dessus). Unfortunately, none of the soloists were named in the programme or, indeed, acknowledged by William Christie at the end of the concert. This was an unfortunate breach of a conductor’s normal concert etiquette, to which he added a display of folded-armed petulance when people tried to leave before a second encore after a long concert. As well as some good singers, he could also have acknowledged some of the instrumentalists, notably Juliette Guignard on continuo viola da gamba and Marie Can Rhijn as a very effective (but alarmingly mobile) continuo organist, adding the distinctive French Baroque ornamented 4/3 cadential suspensions whenever it wasn’t already covered by the singers.

Jesus and Peter in La Reniement de St Pierre. The Stabat Mater pour des religieuses (a particularly appropriate piece for the Abbeye des Dames) and the hymn O crus spec unica represented the crucifixion. The Dialogues inters Magdalenam et Jesum depicted the encounter between Mary-Magdalene and Jesus before the joyous concluding Chants joyeux du temps de Pâques. The 19-strong chorus was generally good, but there was rather too much vibrato from some of the sopranos. Most singers had solo spots, some more than other, with some particularly good low female alto voices (bas-dessus). Unfortunately, none of the soloists were named in the programme or, indeed, acknowledged by William Christie at the end of the concert. This was an unfortunate breach of a conductor’s normal concert etiquette, to which he added a display of folded-armed petulance when people tried to leave before a second encore after a long concert. As well as some good singers, he could also have acknowledged some of the instrumentalists, notably Juliette Guignard on continuo viola da gamba and Marie Can Rhijn as a very effective (but alarmingly mobile) continuo organist, adding the distinctive French Baroque ornamented 4/3 cadential suspensions whenever it wasn’t already covered by the singers.

The last concert of my short stay in Saintes was the lunchtime concert (18 July) given by Vox Luminis directed by Lionel Meunier, the third concert they had given during their residency in Saintes. They contrasted two works not normally associated with each other, Purcell’s 1693 Ode for the Birthday of Queen Mary II: Celebrate this Festival, and Bach’s 1727 Trauer-Ode (Cantata BWV 198), written to commemorate  Christiane Eberhardine, Queen of Poland. Purcell’s Celebrate this Festival is not perhaps the finest of his birthday odes, but it is the most powerful, with some stirring music and a prominent role for trumpet. Bach moving Trauer-Ode perfectly demonstrates the love that the citizens of Leipzig had for the Saxon Electoress Christiane Eberhardine, who refused to follow her husband’s conversion to Catholicism to gain election to the Polish crown. Notionally Queen of Poland, she never went to that country, remaining in exile in Saxony. It formed the centrepiece of a grand commemoration service in the Leipzig St Paul’s University Church. It includes a memorable depiction of the tolling of the bells in an alto recitative, following by the gorgeous Air Wie starb die Heldin so vergnügt, hear sung by the impressive countertenor Daniel Eldersma, accompanied by two violas da gamba and two lutes.

Christiane Eberhardine, Queen of Poland. Purcell’s Celebrate this Festival is not perhaps the finest of his birthday odes, but it is the most powerful, with some stirring music and a prominent role for trumpet. Bach moving Trauer-Ode perfectly demonstrates the love that the citizens of Leipzig had for the Saxon Electoress Christiane Eberhardine, who refused to follow her husband’s conversion to Catholicism to gain election to the Polish crown. Notionally Queen of Poland, she never went to that country, remaining in exile in Saxony. It formed the centrepiece of a grand commemoration service in the Leipzig St Paul’s University Church. It includes a memorable depiction of the tolling of the bells in an alto recitative, following by the gorgeous Air Wie starb die Heldin so vergnügt, hear sung by the impressive countertenor Daniel Eldersma, accompanied by two violas da gamba and two lutes.

The concerts were only part of the musical events taking place during the Festival de Saintes. These included orchestral courses led by Philippe Herreweghe and William Christie, performances by youth orchestras, various conferences and lectures, films, an exhibition of opera costumes, and various activities and music classes for children. Many of the musicians were in residence for a few days, bringing their children with  them. Evenings finished with open-air Columbian-influenced jazz played by the Doña Amelia y su Combo (Alexander Calvo, euphonium, Juliette Macquet, flute, Cristian Ospina, percussion, and Amélie Lejosne, bass). The website for the Abbeye des Dames and the Festival de Saintes can be found here.

them. Evenings finished with open-air Columbian-influenced jazz played by the Doña Amelia y su Combo (Alexander Calvo, euphonium, Juliette Macquet, flute, Cristian Ospina, percussion, and Amélie Lejosne, bass). The website for the Abbeye des Dames and the Festival de Saintes can be found here.

Share this: