by Jayme Russell

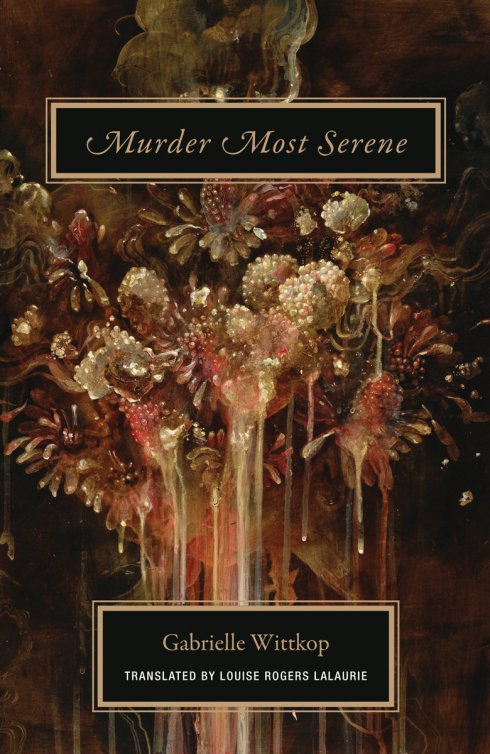

Murder Most Serene by Gabrielle Wittkop and translated by Louise Rogers Lalaurie. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Wakefield Press, October 2015. 116 pages. $12.95, paper.

Murder Most Serene by Gabrielle Wittkop and translated by Louise Rogers Lalaurie. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Wakefield Press, October 2015. 116 pages. $12.95, paper.

Fallen decadence, smearing of gold to tarnished black. The ruined book is curled beside me in bed. It’s pages stiff waves petrified, moving toward an inky putrescent Venice. The book is the physical manifestation of the dark decay within. “There is always something afoot in the city, whose mirrors drink the dark.”

Murder Most Serene. The object fits its title. When opened completely the pages spread like hardened petals, like the “golden hue of dried roses,” pressed. Preserved only for beauty. The vibrancy stolen when plucked and preserved. These roses are infused with toxicity.

One has to only gather the ingredients: hemlock, which releases a yellow sap, like pus, when crushed; fetid, oily rue; lugubrious foxglove, heinous buttercup, euphorbia, or beggar’s weed; datura, the devil’s weed; sedum, known as biting stonecrop; groundsel, known as carpenter’s weed; scilla bulbs and nightshade. One must know how to recognize their dark, textured leaves, their coxcomb serrations or jagged edges, like a shrimp’s tail, their livid berries, the purple stains bloodying the stalks of hemlock, the putrid stink of mandragora, the elegance of monkshood.

Viscous, sharp, and seeping. One must know how to recognize poison. One must make the right choice, know how to make the body react in just the right way. There is the dream of the violent murder scene.

Someone sees themselves in a dream, committing a murder that affords the sensation of a lifetime, a tremendous undertaking, sublimated further still by the voluptuous power of the imagination. Using the shard of a broken bottle, someone slits the throat of a person whose face is nothing but a dark blur. They know very well the victim’s identity, though it will soon be forgotten, by the sticky heat of blood in their hands, the tearing of ripping flesh, the scraping of the glass shard on the granite will remain forever, with the signal fulfillment of the most violent and ancient transgressions.

And then there is the more excruciatingly drawn-out murder by poison, only to be followed again and again by an unseen poisoner.

Catarina arches, tense and rigid, pulled taut, she bucks and rears, huddles and shrieks, as in the grip of her haut-mal seizures. This time, the fruit lurches, heaves, turns over, and breaks, blocked sideways in the pelvic basin. Now she vomits a black sludge mixed with blood, spreading an appalling stench. Standing at the foot of the bed, Rosetta watches and says nothing. Alvise enters the room and takes his wife’s hand, an anxious furrow barring his brow.

If one is willing to watch the female bodies convulse in their death throes. If one is willing to walk the labyrinthine streets filled with carnival and decadent masked costumes, one also must notice the blood spilled in the street from the previous day’s public maiming. And wonder if Alvise is the true murderer.

All that may be conjectured with certainty is that Alvise will marry again, and quickly, because he seems quite incapable of living sans spouse, a mysterious disposition indeed.

The book is a stiffened body, like so many convulsing and stilled inside. All the poisonous liquid of the female body will leak black blood, silver blood, putrid blood from their mouths, and bloat and discolor their distended skin. Their organs will dissolve. Their unborn children will disfigure and die. This is the end for the married woman.

http://wakefieldpress.com/wittkop_murder.html

Share this: