Dir. Fred Zinnemann. Starring Gary Cooper, Grace Kelly, Katy Jurado

The most famous reviews of High Noon are surely the grenades tossed at it by John Wayne and Howard Hawks; both men criticized the story for how it portrays a marshal who utterly fails to rouse his comrades to serve law and order. Hawks’ smear of how Will Kane (Cooper) is bailed out—”by his Quaker wife”—is an unexpected jibe from a man who directed as many decent roles for women as anyone this side of George Cukor. But no matter. Hawks’ dismissal of that pivotal moment in the film is pure reactionary chauvinism, for there are only a handful of individual moments in High Noon which are more effective than the time Amy (Kelly) picks up a gun. The entire movie has been leading up to that moment not in terms of drama, but because the shots in this movie that aren’t extreme close-ups fill the majority of the screen with the focus of said shot; the rest pick up penumbras and the back of other people’s heads. Here’s a representative example, almost a throwaway, from a scene with Helen’s (Katy Jurado) hair.

High Noon searches for ways to make the viewer feel like s/he is inside the picture. Shots like these which are directly on top of a character’s shoulder, or Zinnemann’s preferences for using establishing shots which move rather than statically depict some building or person, help the movie along. So too does the real-time mission to put together enough deputies—the hope is at least a dozen, maybe more—who will make a powerful enough defense force to deter the Miller gang. I’m fond of this one, though, because more than the other elements it reflects the movie’s most vital sequence. Amy has already run off the train which she would have otherwise have taken away from Hadleyville, its inherent danger, and her newlywed husband. Once again, Zinnemann has his eye on two things. He has backgrounded Amy, looking fretfully out the window where the gunfight has begun, and foregrounded a pistol in its holster. The movie knows, though she doesn’t, that she’s going to use the gun.

Amy is a Quaker not because she’s from the Mid-Atlantic or because there’s any tradition of that in her family; she is a Quaker because her father and brother died violently. “They were on the right side,” she says to Helen, “but that didn’t help them any when the shooting started…There’s got to be some better way for people to live.”

However, by the time she’s looking out the window, her husband has been wounded and, after a fine start to the fighting, is about to be outflanked. Without Kane even realizing that Pierce (Robert J. Wilke) is about to shoot him in the back, glass shatters and Pierce falls to the ground dead.His body can be seen in the distance, and then the cut:

It is, of course, another foreground/background piece of work. Zinnemann has the frame angled in such a way as to seriously limit any other perspective on the two of them. It’s just Pierce’s corpse bleeding out in the dirt, the window Amy fired through, and Amy herself, face in the wall. It is not as simple as saving her husband’s life; she does not burst out of the building and jump for joy that only one man remains for her husband to overcome. She crumples up against the window frame and, though we do not see her face, we may well assume her expression. Zinnemann’s movies are filled with moments like these, which is why they still feel vibrant decades after the fact. (No doubt it’s also part of the reason they keep ending up with Best Picture wins.) Faced with the decision to die with a clean conscience or live as a blasphemous hypocrite, More in A Man for All Seasons chooses the block.Faced with the decision to recuperate with his wife or return to the army he’s hiding from, Prewitt in From Here to Eternity chooses to avenge Pearl Harbor. High Noon forces Amy to choose between her husband or her conviction. She chooses her husband over her conscience. And when Kane does shoot down Miller (Ian McDonald) in the middle of the high street, with another little assist from his wife, and the town is successfully protected, his reaction to the group of people who pour out of the houses and shops is famous. He throws down his tin star and rides off with his bride. What’s unseen and unsaid are the long-term scars that Amy will no doubt have to tend to inside herself. What does it mean to be a member of the Society of Friends who sets down one of the primary tenets of the faith and then has to pick it up again? There is no glib answer for that feeling, and there is no instant salve for that hurt.

No wonder, I suppose, that Howard Hawks didn’t like it. When he had Gary Cooper for Sergeant York, the previously pacifistic York engages in some legendary doublethink and accepts his new status as hero. After singlehandedly obliterating a German assault, he explains, in more words than this, that he killed those men to save lives. “Well, York,” his commanding officer says, “what you’ve just told me is the most extraordinary thing of all.” No kidding! York makes peace with his status as war hero; who can say what kind of conflicted feelings Amy will have concerning the man she’s just promised to love until death parts them.

The point of the movie is that it should never have come to this. Only one person, Kane’s mentor, Howe (Lon Chaney, Jr.), has a reason for turning down the town marshal. I’m old, Howe says, and you’ll spend too much time worrying about me and not enough time worrying about yourself. He has a point—Kane is a decent man, and decent men are stupid about things like that—but nobody else makes an argument as convincing and honest as Howe’s. Herb (James Millican) is the first and only recruit Kane can get to help him out, and aside from Howe he makes the most reasonable argument for bailing. When he finds out that he and Kane are the only two men who will stand up to the Miller gang, he immediately equivocates. I have a wife and kids, he says. If I die what’s going to happen to them? It’s not the idea that’s wrong, for Herb makes a fair point. His family will be in the wind if he should die for principle. What makes it feel bad is the fact that he’s hiding behind them. His wife might have been a widow if there were ten other men bunkered down in the streets of Hadleyville; Herb is speaking from cowardice, not from protectiveness. He’s more concerned with his own skin than his wife’s.

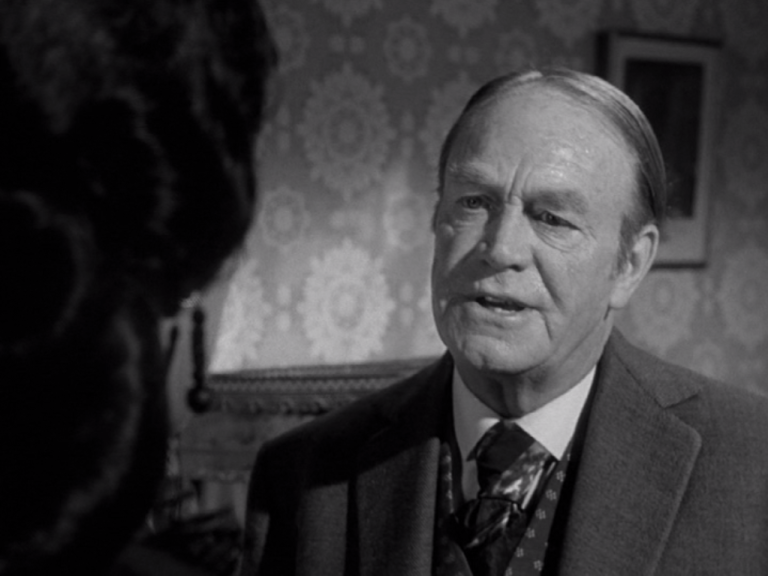

Of all the characters in the film who turn down Kane, no one makes an unkinder cut than the mayor, Henderson (Thomas Mitchell). While sitting in church, Kane comes in to try to make his plea for volunteers. Henderson organizes what becomes an impromptu town meeting, which is a little more pro-Kane than anti-, but saves the last word for himself. This is the best marshal we’ve ever had, Henderson says, silencing the crowd, but there’s more at stake than simply repulsing a group of bandits. The only person they’re really after here is Kane, and Kane’s leaving. If he’s not here, Henderson says, sliding with every sentence into that warm bath of politician-makes-his-stump-speech, then I imagine they’ll leave us alone. And that will be good for Hadleyville, which will continue to hold up its reputation as an up-and-coming place for business as opposed to a lawless shoot-’em-up Wild West town. He singlehandedly eliminates any kind of support Kane will get, cutting his friend off at the knees. It is a breathtaking scene in which one man denounces another; we cannot help but remember that Henderson stood by Kane at his wedding just an hour before, and now the mayor has all but signed Kane’s death warrant.

For a movie which is only about an hour and a half long, High Noon excels at providing a detailed look at the town where it’s set. There’s a saloon that’s full on Sunday, maybe as full as the church a little ways down the road. It evinces a smidgen of diversity, although in a modern High Noon there’s no doubt that Helen would be joined by other Hispanic characters. Will Kane never makes it sound as if he’s going to risk his life for Hadleyville, which is important to note; he refuses to run because he’s never run from anything before in his life. Nor does he want to take the chance that the Miller gang will show up where he is relocating with his wife. Yet even though he isn’t making the choice to protect the town from a little band of invaders come from the depot, it still amazes him that the people he thought he knew would turn out to be so venal. Henderson sells out Kane because he wants to be the mayor of a bigger town with more corporate interests. Helen leaves town because she’s in danger from Miller, who is one of three ex-boyfriends she tangles with in this movie. (Aside from Miller, Helen has also dated Kane and his deputy, Harvey Pell, though presumably not all at the same time. There’s a much longer and better essay out there somewhere about how Katy Jurado is the whore to Grace Kelly’s Madonna, though I know I sure didn’t write it.) Pell refuses to help Kane because Kane refuses to use his influence to make Pell the new marshal. The judge (Otto Kruger) is the first to go: Kane may have caught Miller, but the judge is the one who sentenced him. The men in the saloon are looking forward to picking up Kane’s corpse from the road in the same way they’d dispose of a dead dog. In short, when Kane and Amy leave, the last vestige of decency in this little town will leave with them. What’s more amazing is how many of the townspeople were willing to watch that decency die on a Sunday afternoon rather than defiantly ride away.

Advertisements Share this: