This past spring I took on a new hobby: baking homemade bread. I have long been a home cook, but I had never baked a loaf of bread. One of the key differences between cooking and baking is the balance between art and science. Cooking is much more art than science. In cooking, there are underlying techniques and key steps that must take place, but a cook has tremendous flexibility in how they make a dish, just as an artist has tremendously flexibility in how they paint a picture (Think Van Gogh vs. Picasso vs. Manet). As a cook, you can deviate quite significantly from a standard recipe and get a great result. In baking, the key to success is being precise and scientific. Deviation can bring failure.

Where a cook might take a pinch of salt, a baker measures out an exact ratio of salt to flour. This is known as a baker’s percentage (it really should be called a baker’s ratio IMO, but we will leave that for another blog post). Deviating from a recipe will have tremendous consequences in bread making that are not typically seen in cooking. Add a percent too much salt or too little yeast and your bread will not rise. A bit too much water and the bread will lose structure and be flat (and the dough will be super sticky). Too little water and it will be dense like a bagel. Bake it until it reaches 150 degrees and it will be gummy and undercooked inside despite looking golden brown and delicious on the outside. However, bake it past 160 degrees and it will have that beautiful crumb inside we all know. The reason behind this? Chemistry. Gluten gelatinizes around 160 degrees.

The crumb structure inside bread is due to fermentation and gelatinized gluten

I am not trying to say there is not an art to bread making, there certainly is, but in general, it is a more scientific pursuit than cooking. Just like auditing, is a more science than art in my opinion.

So what does this have to do with being a better auditor? Well actually a lot when you start thinking about it. Results in both bread making and auditing come from good planning and implementation of your plan. If we invest the right time into planning and implementing our plan, we will get a good audit.

What else has it taught me? Patience. Bread making is a long ordeal (well not as long as auditing, but do not expect to get something on the table in 10 minutes). Most artisan breads require a long fermentation. From start to finish, a nice flavorful loaf takes 3 to 4 days to make. Over time, the dough develops and builds flavor if the right ingredients are mixed together. Just like our findings are slowly developed over time using the right mix of condition, criteria, cause, and effect. In the end, we strive for ‘flavorful’ findings. One of the important stages of bread making is “proofing” or proving the bread is alive and rising. Proofing is the last step before baking. With proofing I see some similarities to our quality assurance processes. QA is the stage of an audit where the findings are proved out.

This ciabatta was well proved, with a nice rise and airy texture

Lastly, control is critical. Bread making is all about controlling ingredients, temperature, and time. With good controls in place, you can achieve the same results every time. Every professional baker knows this and that is how they churn out delicious bread every day. Bakers control ingredients by precisely weighing them. Good bread makers never measure by volume, as no two cups of flour are the same and by weight can vary by 25% or more. Auditors should do the same and measure using precise tools. Bakers also control for time and do not try to rush or delay. A baker aims to get the dough into the oven at the right moment. If it is put in the over too early flavor development through fermentation and rising has not occurred. If put in too late after fermentation has ended the bread will lose all the air that was made and the bread will be flat and dense.

This ciabatta did not go into the oven at the right time and came out flat because it was overproved

We should strive to do the same thing and get our reports into the ‘oven’ at the right time by auditing what is relevant now and issuing our reports timely. Lastly, bakers control for temperature to produce a bread with the right characteristics (baguettes only get crispy and crunchy in a hot and steam filled oven). We should consider our tone (e.g. temperature) that we use when ‘baking’ our reports. Sometimes we need a hotter oven and other times we can cool it down.

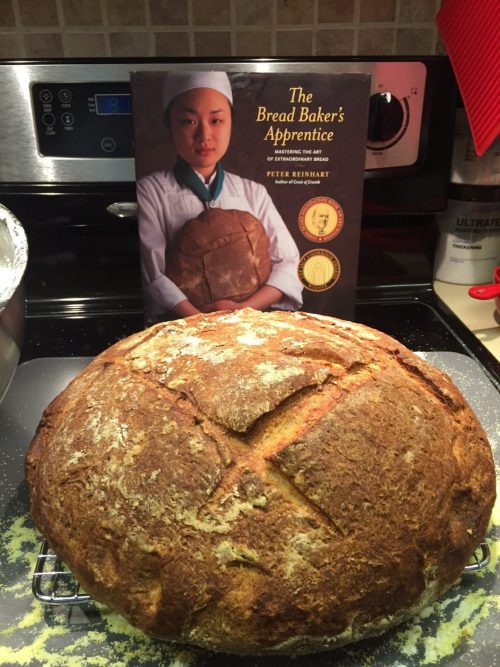

Peter Reinhart has been a valuable resource for me as I learn about bread making. You can listen to his TED talk or get any of his great books on baking if you are interested. He likes to give what he calls his bakers blessing “May your crust be crisp and your bread always rise”. In his honor, I am ending with an auditors blessing: May your findings be impactful and your recommendations always implemented.

First attempt at a Miche, a whole-wheat sourdough loaf

Ian Green, CGAP and OAD Principal Auditor

Share this: