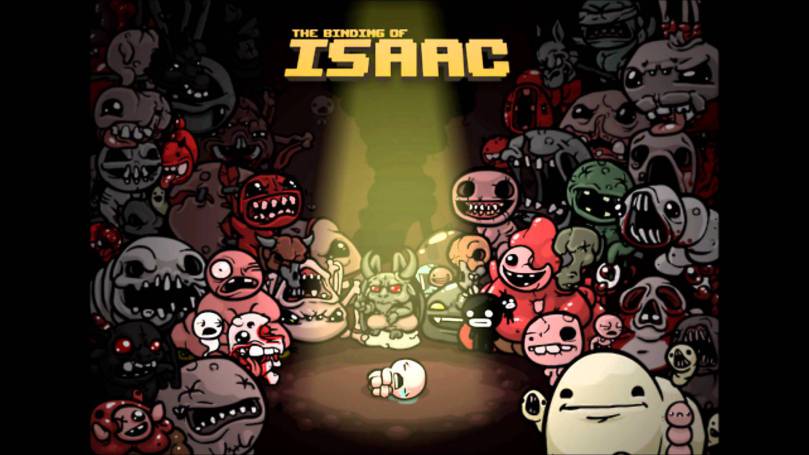

When the words art and game are mentioned together, most would think of the aesthetically pleasing games that are coming out. These games can’t help but draw people in because they’re amazing to look at. It feels like you’re watching a movie while playing a game and people say it’s art. However, can a game without amazing graphics be considered art? I say yes. Art is more than just something that is pleasing to the eyes. There are so many factors into how a game can be considered art. While the Binding of Isaac may not look as great as the games that are currently coming out, it is still art. The Binding of Isaac is an indie roguelike video game originally released in 2011 by Edmund McMillen.

The Binding of Isaac

The Binding of Isaac

The game became such a success that Edmund improved it, changed the engine, and released the Binding of Isaac: Rebirth in 2014. Part of his reasoning for updating the game so shortly after release was posted on his blog saying “I didn’t like the Flash style. Isaac was a big rush job and I did all the art in less than 2 months. I wasn’t ever happy with it and hadn’t planned on the game being so successful so I just got the job done so I could finish the game… the art was lazy and to me, just an eyesore.” I mentioned that art is not just about aesthetics, and I still stand by that, however, if you can improve something and make it better, why not do it? This can apply to artwork, storyline plot holes, or even game sounds. We will come to see how Isaac matters as art.

Rebirth

The Modding of Isaac

Rebirth

The Modding of Isaac

Edmund has come out and said he will no longer be creating content for the Binding of Isaac. However, he created modding tools for the community to add to the content, making the “art” last as long as the community wants to continue it. The popular mods will be added as actual content to the game every once in awhile in the form of “booster packs”. John Sharp (2015) explains that art games “uses innate properties of games—among them interactivity, player goals, and obstacles providing challenge for the player—to create revealing and reflective experiences” (p.12). The community is now creating art games with the modding tools that the author provided. These mods use the framework of the Binding of Isaac but create new possibilities, storylines, obstacles, and experiences for the player. Some of these are simple works that add color to the interface to make it more aesthetically pleasing while others are complex and adds as much content as a normal expansion would. The Binding of Isaac: Antibirth was the first major mod that was released and the amazing thing is that it was created before Edmund had released the modding tools. It took two years of work to create this mod. No one would spend that amount of time creating content for a game if they did not appreciate it, care for it, and want it to be seen as art.

Game modders — amateurs who like to modify commercial games, either by reprogramming them or by adding new assets — tend to be obsessed with games. Creating a game mod can take hundreds or thousands of hours of work, usually without documentation or support from the game’s creators and sometimes having to actively defeat the encryption systems built into the game. This requires considerable dedication. (Kelland 2011, p. 25-26)

The modders that Kelland describes are dedicated gamers that put hours upon hours of work into a game they care about even if they help from the game creators. They don’t expect anything in return for their work except maybe the recognition that their work means something to someone. And in the end, isn’t that the real purpose of art? To give people a sense of appreciation? The modding community has become so large that there is a dedicated website for mods. There are new mods uploaded nearly every day and the community is constantly giving input to each other on how to make improvements. Art is about people coming together and that is what modding does.

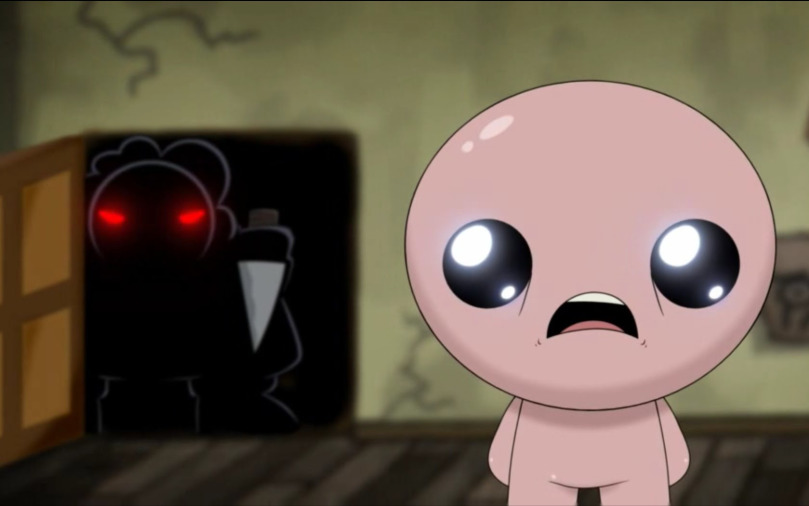

Story Open to InterpretationThe Binding of Isaac has starts off with an introduction scene telling you that Isaac’s mother hears a voice telling her that Isaac is corrupted with sin and that he needs to be saved. She then proceeds to take away his toys, drawings, and clothes. The voice then tells her that he must be cut off from all the evil in the world so she proceeds to lock him in his room with no possessions. Finally, the voice says she must sacrifice her son. She then takes a knife and heads towards his room. Isaac sees what is happening and jumps into a trapdoor he finds under his rug. This is where the game starts. Even though the start of the story is explained to you, there are multiple endings to this game, each unlocked by defeating a major boss. The endings have no story and are not explained to you. It’s just a video and thus having the players come up with an interpretation is part of what makes it art. Many players have come up with their theories as to what the endings mean. Along with the endings, there have been speculations on what the actual meaning behind the game is. This creates an open-ended discussion amongst the game community that does not rely on the author. Roland Barthes says that art must go beyond that of what is given to you by an author:

Isaac sees what is happening and jumps into a trapdoor he finds under his rug. This is where the game starts. Even though the start of the story is explained to you, there are multiple endings to this game, each unlocked by defeating a major boss. The endings have no story and are not explained to you. It’s just a video and thus having the players come up with an interpretation is part of what makes it art. Many players have come up with their theories as to what the endings mean. Along with the endings, there have been speculations on what the actual meaning behind the game is. This creates an open-ended discussion amongst the game community that does not rely on the author. Roland Barthes says that art must go beyond that of what is given to you by an author:

Once the Author is gone, the claim to “decipher” a text becomes quite useless. To give an Author to a text is to impose upon that text a stop clause, to furnish it with a final signification, to close the writing. This conception perfectly suits criticism, which can then take as its major task the discovery of the Author (or his hypostases: society, history, the psyche, freedom) beneath the work: once the Author is discovered, the text is “explained:’ the critic has conquered; hence it is scarcely surprising not only that, historically, the reign of the Author should also have been that of the Critic, but that criticism (even “new criticism”) should be overthrown along with the Author. (Barthes 1977, p. 5)

Barthes talks about the autho r in a sense in which he is not important after he creates his work. Of course the author is important, without him the art would not be created. However, it is not up to him to tell us what the art is. The art of the work is when someone takes what he created and makes it their own by giving their interpretation. We can never really understand what an author intends with his work. Every piece of work leaves an impression on the person who views it in their own way.

r in a sense in which he is not important after he creates his work. Of course the author is important, without him the art would not be created. However, it is not up to him to tell us what the art is. The art of the work is when someone takes what he created and makes it their own by giving their interpretation. We can never really understand what an author intends with his work. Every piece of work leaves an impression on the person who views it in their own way.

There is no end to how much content the Binding of Isaac can provide. People are coming up with new ideas and new creations all the time. Once someone has a taste of it, they’ll want to keep having more. The community wants more people to love the game like they do which is why it feels like they’re trying so hard to make the game into something to be proud of. When playing this game, a mixture of emotions can come up. Sometimes you’ll laugh, frown, feel disgust, but most importantly when it’s all said and done, you’ll feel a sense of awe. Take a step back. Take it all in. Realize what you’re experiencing. See how this game influences you and those that play it.

ConclusionThe Binding of Isaac definitely has flaws like everything else out there. Nothing is perfect. However, the flaws are a part of what makes it unique. The fact that you can add and improve upon it makes it art. The game itself is open to interpretation creating the image that it’s subjective to each individual. Maybe people will convince others to agree with them about the meaning of it all but that’s up to each person to make their decision. Even though Edmund will no longer actively add content, he made sure the art will continue by providing a way for the community to be a part of something that matters to them. Everyone has something that they love so much that they want to share the experience with others. A lot of people love the Binding of Isaac and want it to be appreciated for what it is. And so, we have the reason why the Binding of Isaac matters as art.

Edmund McMillen. 2014. That Guy That Made Those Games Said Those Things and Was in That Movie. [Blog Post]

John Sharp. Works of Game: On the Aesthetics of Games and Art. MIT Press, 2015.

Matt Kelland. 2011. “From Game Mod to Low Budget Film: The Evolution of Machinima.” In The Machinima Reader, edited by H. Lowood and M. Nitsche. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Roland Barthes. (1977 [1967]). “The Death of the Author.” In Image, Music, Text. New York: Hill and Wang.

Advertisements Share this: