The road to hell is paved with good intentions lazily executed.

Fawlty Towers is possibly as close to perfect a TV sitcom as has ever been produced. Even so there are aspects of the show open to debate. For example there is the claim that Manuel, the Spanish waiter, is the most sympathetic of the regular characters. I could not disagree with this claim more. To me there is only one character truly deserving of sympathy on Fawlty Towers and that is Basil Fawlty.

To judge by various comments I’ve encountered sympathy for Manuel seems to be largely based on the idea that because he is at the bottom of the pecking order Manuel is therefore the most vulnerable character and thus most deserving of sympathy. This is very attractive logic because it requires no great mental effort to reach such a conclusion. It certainly requires a blinkered approach but this is part of the appeal, the blinkered approach ensures that the effort of a cross-examination need not be attempted. The Manuel sympathiser need never consider the ease with which hospitality staff, even those with Manuel’s grasp of English, can change jobs (and don’t try to tell me otherwise, after 16 years in hospitality I know how employable even the incompetent are), the Manuel sympathiser need never consider the fact Manuel makes no serious effort to improve and is every bit as hopeless in the last episode as in the first.

Unlike Manuel, hotel owner Basil Fawlty cannot easily escape from the web he is mired in. He cannot simply walk out without leaving behind most, if not all, of everything he has worked years to build. Even if he steeled himself to do just this I doubt his wife would let him entirely escape. Sybil Fawlty comes across to me as a character who needs somebody to bully and mistreat. Even if Basil didn’t return to the hotel I imagine she would insist on torturing him from afar because that’s just who that character is.

So Basil is stuck there, trying to do his best. I don’t claim he’s very good at it but at least he’s trying, which is more than can be said for either Sybil or Manuel, each of whom continually frustrates Basil by their unwillingness to make any real effort.

I like to think of Fawlty Towers as being a reinterpretation of Jean-Paul Sartre’s 1944 play, No Exit. In this version though the three main characters are running a hotel rather than being locked inside of a room. Also in this version the torments of hell are mostly visited upon Basil as the one trapped in the middle. On one side Sybil avoids making any real effort, choosing to nag and bully Basil instead, while on the other side Manuel uses his lack of comprehension as a shield to minimise his own workload. (The harder it is to get a member of staff working the less they will be asked to do. Amazingly on more than one occasion I’ve seen some form of this tactic; pretending incomprehension, excessive slowness, or just plain hiding, work like a charm.)

By this point I imagine you’re wondering to yourself what any of this has to do with the fantastic. Well fair enough, (though if you’re honest with yourself you’ll admit you’re fascinated by this entirely unexpected take on a classic sitcom.) The fact is the sort of scenario I’ve described in Fawlty Towers is common enough in everyday life, where even the most accomplished and highly regarded amongst us are capable of putting others into the unenviable position of Basil Fawlty.

For example in Skyhook #16, published by Redd Boggs in the winter of 1952/53, there is a letter by Jack Vance in which he responds to part of a William Atheling Jr article which appeared in the preceding issue. Unfortunately because I don’t have a copy of Skyhook #15 to hand so I can’t quote the offending comments but I assume Vance didn’t misrepresent what was written about his work since neither Atheling or Boggs remonstrated with Vance in response to the following:

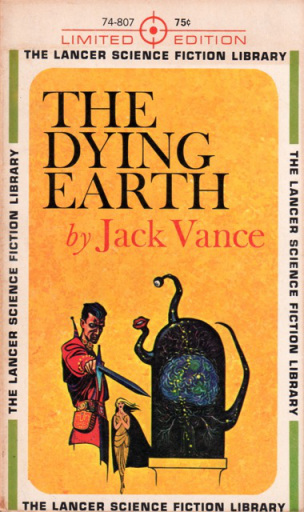

‘A few remarks on Mr Atheling’s article, which was read with wry amusement: (1) Big Planet was suggested, not by Beowulf, not by the Odyssey, but by a short story by the author of Beau Geste, whose name temporarily escapes me – Percival Wren, something like that. A dozen men desert the Foreign Legion; only one survives to reach Tangier. Big Planet naturally evolved considerably from this human-depletion idea; and in its original form – 82,000 – it had an entirely different slant from the one it ended up with. Written originally two or three years ago, it is not, as Mr Atheling assumes, a sample of my latest work. In fact, many of Mr Atheling’s assumptions and inductions do not completely hit the mark. For instance: (2) A person who, reading a collection of short stories while firmly convinced he is reading a novel, cannot fail to put the book down with a trace of dissatisfaction. This is evidently what occurred when Mr Atheling read Dying Earth. I completely concur with his view that, as a novel, this collection of vaguely related short stories makes a “chaotic…shapeless” whole. I believe the notation on the cover, “A Novel by Jack Vance” misled Mr Atheling. (3) Mr Kuttner I esteem highly as a man, a gentleman, a fellow citizen of the U.S., a prolific and talented author, but I must minimise the degree to which his works have influenced my own. There have been, I must assert categorically, absolutely none.’

For the purpose of my argument the matter of what inspired the plot of Big Planet is a secondary matter though we can see that Atheling was already on shaky ground if he was attempting to second-guess an authors inspirations. Tempting as it is to make such pronouncements I suspect correctly tracing literary inspiration is about as easy as discovering the source of the Nile was for 19th century explorers.

It’s with Vance’s next point however that we encounter what surely his Basil Fawlty moment. I’m willing to bet the restrained sarcasm Vance employed in order to agree with Atheling that the short stories contained in The Dying Earth collection made for a terrible novel is as nothing to how he felt when he first read Atheling’s complaint. As somebody who has read The Dying Earth collection, albeit many years ago, the thought that anybody could miss the assorted changes in plot, location, and characters is an astounding one. As the author of these assorted stories and thus more intimately involved with then than any reader could be the Atheling complaint was surely a source of intense frustration for Jack Vance. How do you deal with being told you have failed when the basis of the claim is as demonstrably wrong as this? There are things that should not need explanation, that are a chore, an undeserved burden to set right. If it had been me in Vance’s place the sheer frustration of Atheling’s comments would have had me curling up Basil Fawlty style.

It’s with Vance’s next point however that we encounter what surely his Basil Fawlty moment. I’m willing to bet the restrained sarcasm Vance employed in order to agree with Atheling that the short stories contained in The Dying Earth collection made for a terrible novel is as nothing to how he felt when he first read Atheling’s complaint. As somebody who has read The Dying Earth collection, albeit many years ago, the thought that anybody could miss the assorted changes in plot, location, and characters is an astounding one. As the author of these assorted stories and thus more intimately involved with then than any reader could be the Atheling complaint was surely a source of intense frustration for Jack Vance. How do you deal with being told you have failed when the basis of the claim is as demonstrably wrong as this? There are things that should not need explanation, that are a chore, an undeserved burden to set right. If it had been me in Vance’s place the sheer frustration of Atheling’s comments would have had me curling up Basil Fawlty style.

And then, not content with the above Atheling apparently then went on to rub salt in the would by claiming Vance’s style was influenced by the work of Henry Kuttner. Given Vance had for years been plagued by a persistent rumour that he was nothing but pseudonym of Kuttner I imagine any claim that Kuttner was a major influence would annoy Vance. That such a claim came from the same person who had just mistaken a collection of short stories for a novel should be grounds for unbridled fury.

Under the circumstances I think Jack Vance handled the situation with impressive restraint. I know if it had been me the temptation to unleash an Ellison-like diatribe would be hard to resist.

For the record in Skyhook #16 is another William Atheling article in which he responds to Anthony Boucher pointing out that The Dying Earth was a collection with the following:

‘Mr Boucher is right about the Vance “novel,” technically….’

There is no reaction from William Atheling in regards to Vance’s own letter but perhaps it arrive too late for Redd Boggs to make Atheling aware of its contents before Skyhook #16 was published (it should be remembered that communication was just that little bit more cumbersome back before easy access to the sort of technology we employ today). If Atheling did respond to Jack Vance’s comments it was probably in the form of a private letter.

If there is a conclusion to be had from this situation I think it’s best summed up by quoting Sergeant Phil Esterhaus from Hill Street Blues, “Hey, let’s be careful out there.”

P.S. It should be noted that William Atheling Jr was a pseudonym of the late James Blish. I didn’t mention this earlier because when Skyhook #16 was published this was still a well kept secret. I would also assume Blish either expunged or rewrote the Jack Vance section when preparing the Atheling material for book publication but as I don’t own either The Issue At Hand or More Issues At Hand I can’t confirm this.

P.P.S. Percival Christopher Wren was the author of Beau Geste.

Share this: