In my last post-Las Vegas massacre post, I distinguished between mass public killings (e.g., the Pulse Night Club shooting, the Nice truck attack, the Manchester concert bombing), mass murders (all of the above plus, e.g., Charles Manson, Richard Speck, Joel Smith, Jason Dej-Odoum), and mass shootings (all of the above plus, e.g., the drive by shooting injuring 5 people at a south Houston club yesterday).

Because mass shootings – newly defined as a large number of people injured (including killed) by gunfire (typically 4 or more, as in the Gun Violence Archive) – are a new category of phenomena and I have limited time, I won’t comment on those. The Washington Post, however, has recently acknowledge the definitional challenge I have been addressing.

GENERAL DISCLAIMER FOR THIS AND FOLLOWING POSTS: I present the best data I have seen. Which is not to be confused either with the best in existence or perfect, or even with everything that exists. The best that I have seen. I am not a sociologist of murder, with or without guns. Please respect that I have taken time away from my regular work, my family, and my opportunities for recreation in order to try to bring some light to this heated debate. If you find fault in any of the statistics presented, rather than losing your shit, please suggest in the comments both the flaws and better data that exist. If you would like to write a guest post to show all of your data, as long as I find it valid, I am happy to post it.

Duwe defines mass murder as 4 or more killed in a 24 hour period (to distinguish it from spree and serial killings) and uses data from the FBI’s Supplementary Homicide Reports and newspaper accounts (buy the book and read his 11 page data and methods appendix for an explanation if you’re curious) to construct his database of 909 mass murders from 1900-1999.

YET ANOTHER CAUTIONARY NOTE: Duwe’s is not a study of “Mass Murder with Firearms” like that conducted by the Congressional Research Service. As I have said, if we want to understand death, including only one mechanism of death is too limiting (even if it is the most common mechanism – by that logic we should only study semi-automatic pistol homicides, not gun homicides in general).

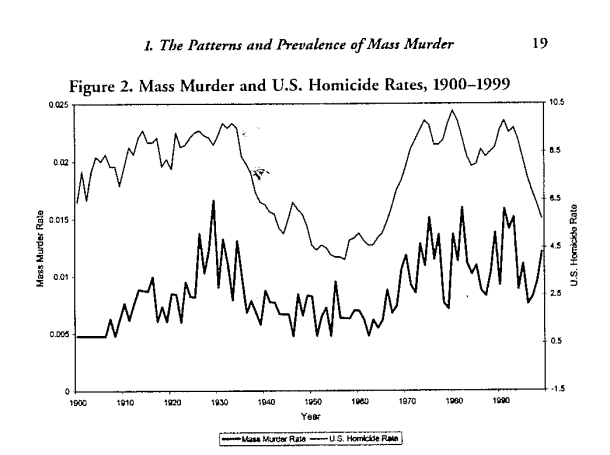

In the interest of time, I present one figure from his book and one table from Duwe’s 2004 article in Justice Quarterly (which is the same as Table 2 in the book but the printing is larger and easier to read).

This figure highlights two important facts about mass murder in the United States:

Issues that this table does not address:

Just a couple of observations from this table of interest to me:

Whether this has changed in the 21st century is an interesting question and I am presently looking for data that are comparable to Duwe’s to address it.

Nothing here is to say that mass murder is not a problem, but Duwe’s work provides an interesting historical perspective and important historical baseline from which we can consider mass murder today.

Mass murder has a long history in the United States. It is not a new phenomenon, which suggests that addressing it might require understanding its very deep roots.

These data also seem to suggest that if we can understand murder in general, we will go a long way toward understanding mass murder in general. Recognizing also that some events are so extreme and rare that they cannot be explained in general.

Advertisements Share this: