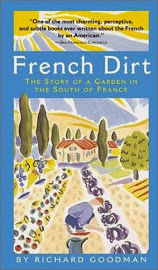

I read this book several years ago and fell in love with it. When I pitched my own (still unfinished) book to Algonquin, I was asked if I had read French Dirt. Oui. A couple of times. Little did I know that a few years later I would be introduced to Richard Goodman through a mutual friend, Jo Maeder, albeit by email. Richard is a seriously talented writer. A recent post on his blog has proven his way with words once again. He is a poet. Paris on a rainy day. My dream at the moment. And when you are finished reading this, open a bottle of red. Start a fire. Curl up under a soft blanket. And fire up Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris. You deserve a trip to Paris. We all do.

Merci, Richard. Bon appétit!

Paris in bad weather “Then there was the bad weather,” begins Ernest Hemingway’s memoir of living in Paris in the twenties, A Moveable Feast. “It would come in one day when the fall was over. We would have to shut the windows in the night against the rain and the cold wind would strip the leaves from the trees in the Place Contrescarpe. The leaves lay sodden in the rain and the wind drove the rain against the big green autobus in the terminal….”I’m not dumb. Start with Hemingway.

Hemingway knew exactly what he was doing when he began his poem to Paris with a cold, rainy, windswept day. He knew that bad weather brings out the lyrical in Paris and in the visitor, too. It summons up feelings of regret, loss, sadness—and in the case of the first pangs of winter—intimations of mortality. The stuff of poetry. And of keen memories. The soul aches in a kind of unappeasable ecstasy of melancholy. Anyone who has not passed a chill, rainy day in Paris will have an incomplete vision of the city, and of him- or herself in it.

Great photographers like André Kertész understood how splendid Paris looks awash in gray and painted with rain. His book, J’aime Paris, shot entirely in black and white over the course of forty years, draws heavily on foul weather. I don’t know of anyone, with the possible exceptions of Atget and Cartier-Bresson, who has come closer to capturing the soul of Paris with a camera. The viewer will remember many of these photographs—even if he or she can’t name the photographer—because they have become part of the Parisian landscape in our minds’ eyes. That solitary man, his coat windblown as he walks toward wet cobblestones; the statue of Henry IV on horseback reflected in a puddle fringed by—yes—those sodden leaves. Kertész’s Paris sends a nostalgic chill through our bodies.

On one memorable trip to Paris, it rained. When it didn’t rain, it threatened to. This was in October, so leaves were starting to fall from trees, and that added a sense of forlornness to my visit. Each morning, I stepped out from my hotel on the Left Bank just off the Boulevard St. Germain into a dull gray morning. The sky hung low, the color of graphite, and it seemed just as heavy. The air was cool and dense.

But I wasn’t disappointed. After a shot of bitter espresso, I was ready to go. That week in October I set myself the goal of following the flow of the Seine, walking from one end of Paris to the other. I had bad weather as my companion, and a good one it was, too. I walked along the quays and over the bridges in a soft drizzle. The colossal bronze figures that hang off the side of the Pont Mirabeau were wet and streaming. The Eiffel Tower lost its summit in the fog. The cars and autobuses made hissing noises as they flowed by on wet pavement. The Seine was flecked with pellets of rain. The dark, varnished houseboats, so long a fixture on the river, had their lights shining invitingly out of pilothouses. The facade of Notre Dame in the gloom sent a medieval shudder through me. None of this I would have seen in the sunlight.

Then there is the matter of food.

There may be no Parisian experience as gratifying as walking out of the rain or cold into a welcoming, warm bistro. There is the taking off of the heavy wet coat and hat and then the sitting down to one of the meals the French seemed to have created expressly for days such as this: pot-au-feu or cassoulet or choucroute.

I remember one rainy day on this trip in particular. I walked in out of the wet, sat down and ordered the house specialty, pot-au-feu. For those unfamiliar with this poem, do not seek enlightenment in the dictionary. It will tell you that pot-au-feu is “a dish of boiled meat and vegetables, the broth of which is usually served separately.” This sounds like British cooking, not French, and the dictionary should be sued for libel. My spirits rose as the large smoking bowl was brought to my table along with bread and wine. I let the broth rise up to my face, the concentrated beauty of France. Then I took that first large spoonful into my mouth. The savory meat and vegetables and intense broth traveled to my belly. I was restored.

I sat and ate in the bistro and watched the people hurry by outside bent against the weather. I heard the tat, tat, tat of the rain as it beat against the bistro glass. The trees on the street were skeletal and looked defenseless. Where had I seen this before? In what book of photographs about Paris? I looked around inside and saw others like myself being braced by a meal such as mine and by the warmth of the room. The sounds of conversation and of crockery softly rattling filled the air. Efficient waiters flowed by, distinguished men with long white aprons, working elegantly. Delicious food was being brought out of the kitchen, and I watched as it was put in front of expectant diners. Every so often the front door would open, and a new refugee would enter, shuddering, with umbrella and dripping coat, a dramatic reminder that outside was no cinema.

I finished my meal slowly. I had left almost all vestiges of cold behind. My waiter took the plates away. Then he brought me a small, potent espresso. I lingered over it, savoring each drop. I looked outside. It would be good to stay here a bit longer.

I got up to go. Paris—gloomy, darkly beautiful Paris—was waiting.

Share this:

![Loving Day: A Novel by [Johnson, Mat]](/ai/067/426/67426.jpg)