When I was an undergraduate, I signed up for an English course that was supposed to spend the entire semester examining only two novels: George Eliot’s Middlemarch and Charles Dickens’ Bleak House. I had already read and loved a couple of Dickens novels, but I had yet to read Eliot, and spending half a semester relishing every bit of her magnum opus sounded like just the nerd-fantasy I had envisioned when I pictured being an English major. Sadly, not enough of my fellow English majors agreed with me, and the course was cancelled when not enough people signed up. I was heartbroken enough to still think of it wistfully, and it put me off of reading Middlemarch for a while. It was as if knowing that I could have dissected it in a classroom setting made the thought of going it alone seem insurmountable.

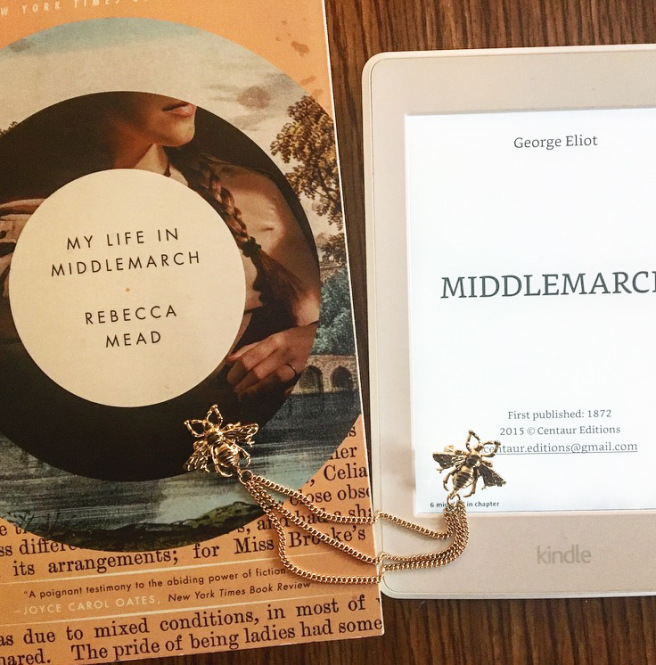

Upon acquiring an ereader, however, the door-stopping tome became more manageable, something I could carry in my purse and read in pieces during lunch breaks at work. With the physical limitations out of the way, I thought maybe I could do it at my own pace, the way I used to read classics pre-English classrooms. I read Books 1 and 2 in between reading other books, in little pockets of time, until suddenly, I wasn’t stringing the project together bit by bit anymore. Instead, I found myself wanting to stay in the book for longer periods of time. I found myself not wanting to break it up with other books or save it for bite-sized moments of my day. Middlemarch became a page-turner without my even realizing it, the way one typically thinks of genre fiction. And by the time I was done with the massive book, I found I wasn’t quite ready to leave the world and its characters behind–luckily, I had Rebecca Mead to ease my transition back into Books That Aren’t Middlemarch.

In case the above didn’t make it clear, I loved Middlemarch. I knew almost nothing about it going in, and that element was kind of fun, so I’m hesitant to try to condense its expansive landscape into a plot summary. Its full title is Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life, and that title is both completely apt and completely misleading. Middlemarch is a novel that focuses on a fictional English town in the 1830s. It follows the lives of many characters, tracing the way their stories intersect (as the lives of small-town residents so often do). It captures the personality of such a town, the way its collective consciousness can shape into stifling expectations and esoteric codes of decorum that can seem silly when penetrated by the narrator’s sharp eye. But it’s a novel full of humor and warmth for the people inside of it, and its commentary never comes off as too caustic to be heard, too judgemental to be lived in. Middlemarch shocked me with how funny it is, and it is at its funniest when it reminds me precisely of people in my life, and of home communities I have shared with them.

And that was thing that turned the novel into a page-turner, and into one of my new favorite novels of all time. It is not merely a “study” of provincial life, but the experience of that life itself. The characters in Middlemarch feel so real that you miss them when the book is over. (In fact, they often reminded me so much of people I knew that I missed those people while I was reading the book.) Eliot’s narrator is one of the most insightful and precise I’ve ever encountered: she describes human patterns, interactions, and secret habits with such authenticity that it’s both destabilizing and completely enveloping. Eliot gets you, and she gets your friends, and she gets the weirdness of crashing through life’s uncertainties with nothing but your best intentions and your worst impulses. Reading it is a marvel, and I was so genuinely sad when the last page flickered off my screen.

That’s why I was so happy to have Rebecca Mead’s My Life in Middlemarch to pick up immediately after, as a way to keep conversing with these characters, to try to stay in their world a bit longer. Mead understands what it means to love this novel: she encountered it as a teenager and has revisited it throughout life. Her own book is a mix of literary criticism of the novel, biography of Eliot, travelogue about visiting the places where Eliot lived and wrote, and memoir about the times when Middlemarch helped illuminate a piece of Mead’s life, or Mead’s life took a turn that helped her appreciate a new element of the novel. For as many modes of nonfiction writing that are present in this book, the premise is fairly simple–a favorite book can be looked at through many lenses (sometimes literally, when one travels to the places the author worked and views manuscripts in museums under gloved hands). This simple premise really resonated with me, though, and definitely makes me want to do more of my own literary-tourism and read more about the lives of my favorite authors. Just as the characters in Middlemarch are often surprisingly intertwined, you never know what sort of connection you might unearth to something that’s felt so familiar for so many years.

If you’re someone who’s intimidated by books that often get characterized as “classics,” especially those the size of bricks, I encourage you to give Middlemarch a try anyway. As you settle into the language, the storytelling, and the web of connection between the narratives, you’ll feel like you’re settling into a real place–and that might be because the book is telling you more about the real community you do live in, and the people inside of it who make up your own web.

Advertisements Share this: