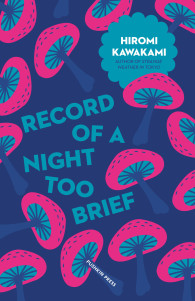

This is the story of Izanami, the Goddess of the Realm of the Dead, and of Namima, the mortal who became her priestess in death.

There’s also this section about fishermen, and how Izanaki’s not actually such a bad guy… I think. Maybe.

Summary

From Goodreads:

In a place like no other, on a mystical island in the shape of tear drop, two sisters are born into a family of oracles. Kamikuu is admired far and wide for her otherworldly beauty; small and headstrong Namima learns to live in her sister’s shadow. On her sixth birthday, Kamikuu is chosen to become the next Oracle, serving the realm of light, while Namima is forced to serve the realm of darkness—destined to spend eternity guiding the spirits of the deceased to the underworld.

As the sisters serve opposite fates, Namima embarks on a journey that takes her from the experience of first love to the aftermath of scalding betrayal. Caught in an elaborate web of treachery, she travels between the land of the living and the Realm of the Dead, seeking vengeance and closure.

Preliminary ImpressionsI was excited to read this book – a book inspired by Japanese mythology, by an actual Japanese person, translated from Japanese! What are the chances here in small-town USA? Then I found this quote in a Goodreads review:

“A human life means nothing to a god and can be taken away at will. But for you… you’re human, and that makes you hesitate. Gods and humans are different. My suffering and yours are different.”

“Then, Izanami-sama, why do you suffer?” I asked, without thinking.

“Because I am a female god.”

Yikes. So it’s going to be that kind of goddess story.

WritingFirst off: The Goddess Chronicle is, as I said, translated. When I critique the writing itself, it’s with the asterisk that I’m only picking at the translator’s words, not Kirino’s. The blame or praise for characterization and construction of the story, I think, is more half and half, split between Kirino and Rebecca Copeland. I have no idea how much was improved or lost by the act of translation.

On a basic level, the writing is awkward. I don’t know if it’s meant to mimic Kirino’s, or if Copeland just isn’t particularly adept at the stylistic side of translation, but this kind of writing is what I expect to find in second-rate MG novels, not adult literary mythology retellings.

I continued to weep and wail, but my father and brothers set off down the path, refusing to turn back. I stood beside the gate until the break of day. I was terrified of the burial ground. …Now I had been thrown into this unfamiliar world, held there by a formidable gate.

It’s just awkward. Stilted and formal, the writing holds us at arm’s length, reciting the facts of the story without bothering to come down to a personal level, elicit real emotions, or build the story organically. At the same time, the characters’ reactions are very dramatic. The emotions we’re told about are Big Emotions, but it simply doesn’t – for lack of a better word – translate.

At some points in the story, this works. For example, Izanami is an inherently dramatic character – she’s a goddess, so of course, at some points, she earns the melodrama. Izanami is the scene-stealer. And, towards the very end of the novel, in the last twenty pages or so, the writing fits the tone of the action. But even in those cases, it’s a case of the story transcending the mediocre writing, not the writing ascending to the level of the story. And outside of a handful of scenes, the writing is, at best, a hindrance to enjoyment.

Translating is hard, but I really wish this story could have been told more deftly.

CharactersPicture this: you’re summarizing a story about a literal goddess and the dead woman who’s become this goddess’s only handmaiden and confidante. But when asked, under oath (don’t question it), who the most fleshed-out character is, you are compelled to say: “The goddess’s deadbeat god husband.”

I wasn’t especially thrilled that this novel looked ready to fall into Memoirs of Helen of Troy-level woman-worshipping, but it’s almost worse that its female characters turned out to be so heckin’ boring (besides, as I’ve said, Izanami).

Namima is a glorified frame story, though her frame story section takes up a large portion of the novel. Granted, her family and Izanami’s do come together in a mildly interesting way towards the conclusion, but there’s still really not much to Namima except as – you guessed it – a betrayed wife, a baby-maker, and then as Izanami’s aforementioned confidante. Namima’s sister, Kamikuu, has almost no characterization; she’s defined solely by her religious station, which is, judging by the novel’s content, praying baby-maker! Yay!

Nearly all the other women in the story are romantic objects; usually it’s their beauty that made them desirable. Spoiler alert here: most of them died, victims of Izanami’s jealousy.

I’m so tired. I expected better.

Izanaki has his own full part of the story, in which his third-person narration takes the reins from Namima’s first-person one. Like I said, he is, probably, the most fully fleshed-out character, which is weird, given that a lot of his memories of early godhood are hazy, and he doesn’t remember Izanami that well (charming). He’s not a good person, either. He has, however, the most compelling and the most complete emotional arc, even if it did rub me the wrong way, and, believe me, it did. It’s just a whole unsettling situation.

But let’s talk about Izanami. Izanami is powerful and terrifying. Her bitterness is her crowning glory. Usually, I don’t enjoy a negative attribute when it forms a character’s whole deal; I don’t like that kind of romanticization. But you can play with that concept when you have gods on your plate, and what Kirino did with Izanami – extending her power from just “taking dead people to the Underworld” to this constant, cosmic comeuppance for Izanaki’s sins against her – is really impressive. It could have sent chills up my spine if the translator had been better (or maybe had better text to work with). Her characterization is consistent and godlike, and she, alone of the main characters, has a solid, emotionally resonant reason for behaving the way she does. To be honest, I’ve never (or at least rarely) had an experience where I read about a deity like her – cruel and remorseless, yet somehow understandable and even, almost, justified in her actions, the way Mother Nature is justified – and was truly affected by it.

Izanami deserved better than this novel and this translation.

Writing LessonsIf you ever get published internationally, cross your fingers and pray for a good translator.

Try not to make one of the most morally questionable characters the most emotionally fulfilling one as well.

There is something to be said for bitter endings. Not for all stories, not all the time, but a well-placed turning of a character’s back on being “happy”? That can show authorial guts, and can bring the story to a satisfying close. It all depends on theme. Tbh, I don’t know how a story about the Goddess of Death’s thousand-year grudge against her dirtbag ex could end otherwise.

Closing RemarksI read The Goddess Chronicle in three sittings for this blog, all today, which is why I am very late. But I hope it proves how dedicated I am, that I slogged through a bad translation with sketchy characters to write this review.

None of the few books I’ve read taken from Japanese mythology have been winners, but I’ll keep trying! We’ll find one someday! It’s one of my new quests, along with “start that Funny Series” and “do some podcast reviews.”

But for now, give The Goddess Chronicle a skip, unless you’ve got a Goddess of Death craving after Thor: Ragnarok and you just can’t find it any other way.

Advertisements Share this: