Terence Byrnes (Photo: Patricia Woodburn)

Terence Byrnes (Photo: Patricia Woodburn)

Off the Page is a regular interview series featuring National Magazine Award winners. In this interview, we chat with Montreal-based writer and photographer Terence Byrnes. Last year at the NMAs, Terence was awarded the gold medal in the category of Photography: Photojournalism & Photo Essay for “South of Buck Creek.” Byrnes succinctly captures the premise of the photo essay by way of a subheading: “A Canadian memoir of black and white in America’s unhappiest city.” Read on for Terence’s thoughts on maintaining sympathetic neutrality towards the residents of Springfield, Ohio; smart phones and the democratization of photography; and his advice for emerging photographers.

First, congratulations on winning gold at the NMAs for “South of Buck Creek,” published in Geist. Your photo essay describes Buck Creek as a “cabinet of wonders.” In your career as a photographer, have you found other subjects, or places, that could be described as such?

I shot for a while in Buffalo when that city was among the rustiest of rust-belt towns. The industrial desolation, abandonment, and sense of fallen empire were awe-inspiring. In a residential area, I saw a man, wearing only dirty white briefs, roasting a wiener in a hubcap where he had built a fire with twigs. This was at the end of a street of McMansions protected with black iron grillwork over every door and window. Is that a wonder? I don’t know.

The essay portion of your piece notes that you took approximately 10,000 photos of Buck Creek, over a span of 45 years. How do you organize all of your photos?

Ten thousand was a guess. It’s more than that. Many are negatives, with some chromes. I worked from proof sheets to produce scans on a Nikon scanner. I moved to digital capture in 2003. Lightroom keeps track of it for me.

Do you have an absolute favourite from those 10,000 photos?

One day, I was photographing an oddly shaped building—it may even have been a skinny parallelogram—that housed a bar. “Bob City” was painted on one end of it. Railroad tracks, a sidewalk, and several streets converged and diverged behind the building, and dandelions had popped up in a patch of grass in front of it. I spent about 45 minutes finding the right position and height to put these elements into proper relation with each other. When I processed the film (this was probably 30 years ago) air bubbles had stuck to the best frame in the series, rendering it unusable. Wanting to salvage that frame eventually led me to early digital scanning of negatives and moved me out of the darkroom to the screen, where I patched the bubbles. I can’t say if this image was an “absolute favourite,” but it’s got a lot of history stored in it.

Within the first few pages of the photo essay, we jump from the sixties with “Terria (1966)” to the early 2000s with “South of Buck Creek” (2001), then to the 90s, with “Joy (1999).” What were your intentions behind the non-chronological organization of this photo essay?

“Intuitions” is probably a better word that “intentions.” When you establish an order for a photographic series, some arrangements just look better. I suppose I want the eye to re-orient itself to the formal elements of each image so the photograph is actually seen. Also, ordering by year suggests development of some sort, or it implies a narrative. As it was, the images themselves were my first priority.

Very early on in the photo essay, you state that your role in Buck Creek shifted from spectator to participant. Certainly, that theme—of your enmeshment in the Buck Creek community—runs throughout: there’s the “crazy moment” when you “fantasized about adopting” one of the boys from the Vision for Youth residence; you carried the “Friends (1977)” photo around for years, hoping to eventually deliver it to one of the photo’s subjects, “scary guy.” What challenges came along with crossing that line from spectator to participant?

Great question. I had to maintain sympathetic neutrality toward everyone and to learn—more than once— that folks who looked down-and-out could be as smart, respectful, and as deserving of respect, as anyone else. Honesty and openness were crucially important. A subject might say, “Take my picture, but don’t ever use it,” and my agreement would have to be as good as gold. People were blown away when I would come back a year later with free photographs. That’s how the street cred developed. Of course, there were rough spots and challenges that were both emotional and physical. I saw families living in misery and stripped of dignity thanks to bad luck, fear of gang activity, and profound physical and emotional disability (with no health care or institutional support). You want to help, but you can’t.

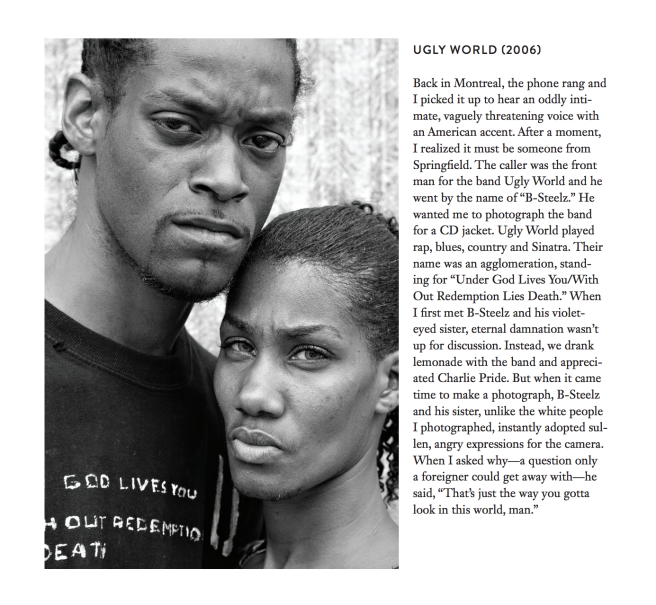

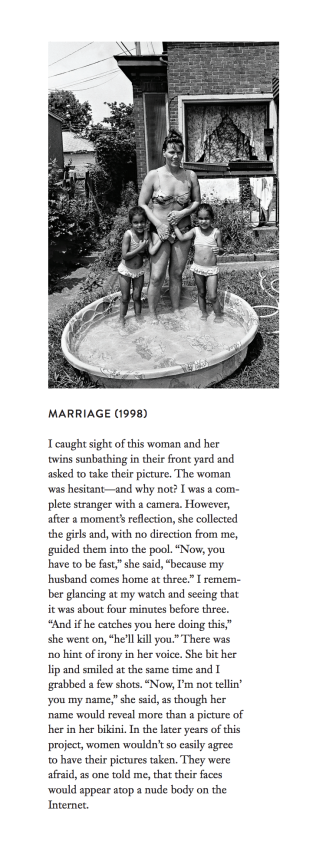

“Marriage (1998)” features a woman in her bikini, with her two twin daughters. The narrative portion states, “In the later years of this project, women wouldn’t so easily agree to have their pictures taken. They were afraid, as one told me, that their faces would appear atop a nude body on the Internet.” It seems that while the Internet has encouraged people to document their lives—via Facebook, YouTube, Instagram—it’s also made it more difficult for photographers to act as the documentarian. Are there other ways in which the growth of social media and the shift to digital have impacted your career as a photographer?

Camera phones have, in a sense, radically democratized photography and, for many people, have done away with the cachet of the physical print. Academic criticism and identity politics have also had a less than salutary effect on the documentary form. Some months ago, I glanced outside my window here in the Point-Saint-Charles district of Montreal and saw an 11-year-old boy got up in a home-made superhero costume, holding a garbage can lid as a shield. I knew it was pure Arbus, but couldn’t resist. When I asked the boy if I could take a photograph, a teenage girl ran up and began shouting at me. Her assumption—thanks to her familiarity with internet images—was that I was about to do something that was immoral as well as illegal.

Your first camera was an Agfa Ambi Silette loaded with Tri-X film. These days, what’s your camera of choice?

Actually, before the Agfa, there was a Kodak “Pony,” which I had forgotten. You’ve caught me at a crossroads now, though. Should I move up from my Nikon D810 to the new D850 or switch to the mirrorless Sony A7R III? Probably the new Nikon.

In 2008, you published Closer to Home: The Author and the Author Portrait, which you had worked on for 10 years. That means that there was some crossover between the literary portraits and Buck Creek. What similarities were there between these two seemingly very different projects?

Both were closer to the subjects’ homes than to the studio. I tend to shoot on-site and to make it up as I go along. This can produce really banal results, but also great surprises in lighting, posture, expression, and mood.

What was the impact—personally and/or professionally—of winning a National Magazine Award?

I think it makes me an easier sell to editors who don’t know me. And if I pitch an idea, I’m more likely to be listened to.

What advice would you offer to a young photographer?

The advice I give myself is often so disastrous that I should keep my own counsel. That said, I think of current work that catches my eye. I love the work of Tamas Deszo, Sebastián Liste, and Ruth Kaplan. Or Michel Huneault’s photographs of Lac Mégantic after the train disaster. There are some wonderful documentarians out there who do far more than record event. I would have been interested in photographing the refugees/migrants who streamed across the border in Quebec’s Eastern Townships in the belief they would find a home in Canada. Good projects don’t have to be topical, but they do have to be fresh.

Previous to Byrnes’ NMA gold award, he received two NMA honourable mentions. The first was in 2009, for “The Imagined Portrait” published in Queen’s Quarterly. The second was in 2012 for “The Missing Piece,” published in The Walrus. For more information on Byrnes’ photography and writing projects, please visit his website.

Interview conducted by Leah Edwards.

The call for entries for the 2018 National Magazine Awards is open now until January 22.

Share it!

![Baaz by [Chauhan, Anuja]](/ai/076/618/76618.jpg)