“First houses are the grounds of our first experience. Crawling about at floor level, room by room, we discover laws that we will apply later to the world at large,” the Australian writer, David Malouf, has written in his memoir 12 Edmondstone Street. “The house is a field of dense affinities laid down, each one, with almost physical power, in the life we share with all that in being ‘familiar’ has become essential to us, inseparable from what we are.”

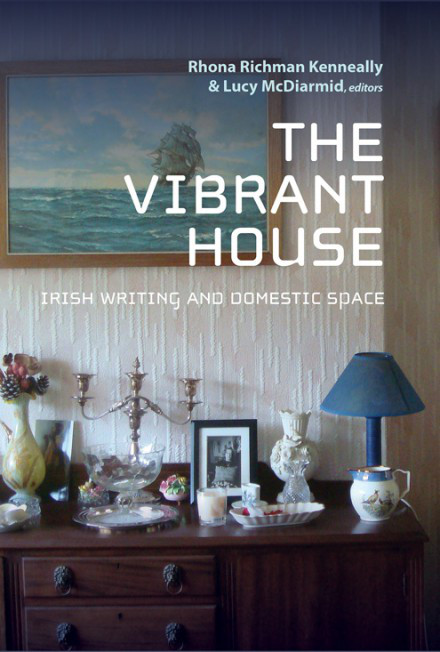

This is the territory of The Vibrant House from Four Courts Press, a new book with contributions from writers and academics on the notion of the Irish domestic space.

I’m in there, not just in the text, but in the visual elements of the book, not least in this beautifully composed cover, photographed by Rhona Richman Keneally, one of the editors of the volume. This image has particular resonance for me because it shows the dining room in my family home in Rathgar – my first and only childhood house – as it was when my mother was alive. (She died earlier this year.)

My mother is not the subject of my contribution to The Vibrant House, which is a speculative memoir of my father (who died in 1970) as glimpsed through the pictures he chose to hang on the walls when we were growing up. The painting of the masted ship on the tossed sea featured on the cover is not one I discuss in the essay but the sideboard itself with all its familiar ornaments and knick-knacks has, since my mother’s death, gained a memorial significance. It’s a shrine to my mother’s aesthetic which has been smuggled into the book like a visual afterthought.

The sideboard stood in the “good” room of the house – i.e. the least used. It hosts an array of objects, each of which carries a memory capsule.

Take the blue-rimmed pheasant jug, for instance. This was only ever used, as I recall, when my uncle came to visit, for dispensing water to go with his whiskey. My uncle was fond of his spirits and my father, a tee-totaller, doled out his ration in small doses. In fact he reserved a separate, marked bottle for his brother, so he could keep track of his consumption. This was in the days where there was little fear of being nabbed for drunk driving; all the same, my father worried about sending my uncle off into the night with too much on board. The pheasant jug was optimistically offered in the hope that dilution might slow the inebriation process. Its contents, more often than not, remained untouched.

The ceremonial candelabra (a wedding present, maybe?) was also only brought out on state occasions – a few Christmas day dinners. It was part of a set – there was a silver platter, also visible on the sideboard, and a tea service that went with it, which is probably still stowed away behind lock and key in the cupboard below, alongside the whiskey, which, after my uncle’s death was only ever used for lacing the Christmas cake mixture.

The white Belleek vase – to the right of the photo frame – encrusted with fat birds perched on thorny branches with china florets, was also a gift, from my aunt. She was my father’s sister and a nun. In those days – the 1960s – nuns often received very expensive presents which they regifted in keeping with the spirit of their vows of poverty. So we got the Belleek vases. Yes, originally a pair. The other one came a cropper when my brothers played football in the house one night when my parents were out and de-perched several of the singing birds. There was some furious gluing activity with sticks of Uhu as we tried to reattach the broken birds, but our repairs were amateurish and the damage was discovered. The vase must have been mortally wounded as there’s now only one left, and this one on show is the unmolested one, I’m pretty sure.

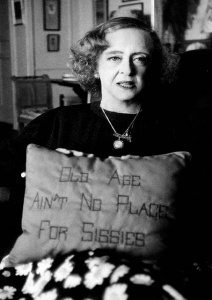

Finally, the framed photograph is not, as you might expect, a family snap, but features a postcard of Bette Davis – sent to my mother by my sister. In it, she’s holding up a cushion on which the words – “Old Age ain’t no place for Sissies” – have been embroidered. My mother really liked this image – so much so that she got it framed. She was an avid film fan, and was partial to Bette. But it was the sentiment of the sardonic message she really identified with. She often cited Bette’s cushion motto in her latter years, when she faced the indignities and disabilities of old age herself with pragmatism, fortitude and implacable good humour.

Finally, the framed photograph is not, as you might expect, a family snap, but features a postcard of Bette Davis – sent to my mother by my sister. In it, she’s holding up a cushion on which the words – “Old Age ain’t no place for Sissies” – have been embroidered. My mother really liked this image – so much so that she got it framed. She was an avid film fan, and was partial to Bette. But it was the sentiment of the sardonic message she really identified with. She often cited Bette’s cushion motto in her latter years, when she faced the indignities and disabilities of old age herself with pragmatism, fortitude and implacable good humour.

The Vibrant House: Irish Writing and Domestic Space; edited by Rhona Richman Kenneally and Lucy McDiarmid, will be launched at Poetry Ireland, 11 Parnell Square East, Dublin, on December 9, @ 4pm.

Share this: