There Once Lived a Mother Who Loved Her Children Until They Moved Back In: Three Novellas About Family is the newest work published in English by Russian author Ludmilla Petrushevskaya. The New York Times believes her to be ‘one of Russia’s best living writers… her tales inhabit a borderline between this world and the next’.

The blurb of There Once Lived a Mother… states that in these ‘darkly imagined’ novellas, ‘both cruelty and love dominate relationships between husband and wife, mother and child… Blending horror with satire, fantasy with haunting truth, Ludmilla Petrushevskaya’s newly translated tales create a cast of unlikely heroines in a carnivalesque world of extremes’.

Anna Summers has translated the book, and has also penned its informative introduction. At the outset, she sets out the ‘story-swapping culture’ which exists in Russia, and goes on to inform us that ‘the three novellas in this volume tell extreme stories that couldn’t be heard for many years – censorship wouldn’t allow it’. Summers believes that Petrushevskaya is incredibly important within the Russian canon, describing, as she does, ‘in minute detail how ordinary people, Muscovites, lived from day to day in their identical cramped apartments… She spoke for all those who suffered domestic hell in silence, the way Solzhenitsyn spoke for the countless nameless political prisoners’.

Anna Summers has translated the book, and has also penned its informative introduction. At the outset, she sets out the ‘story-swapping culture’ which exists in Russia, and goes on to inform us that ‘the three novellas in this volume tell extreme stories that couldn’t be heard for many years – censorship wouldn’t allow it’. Summers believes that Petrushevskaya is incredibly important within the Russian canon, describing, as she does, ‘in minute detail how ordinary people, Muscovites, lived from day to day in their identical cramped apartments… She spoke for all those who suffered domestic hell in silence, the way Solzhenitsyn spoke for the countless nameless political prisoners’.

Of the author’s protagonists, Summers says the following: ‘Reading Petrushevskaya is an unforgettable experience. This testifies to the exceptional power of her art, because her characters, by their own admission, don’t make particularly fascinating subjects. In this volume, her heroines are tired, scared, impoverished women who have been devastated by domestic tragedies… Such women are boring even to themselves’.

The three novellas within There Once Lived a Mother… are entitled ‘The Time Is Night’, ‘Chocolates with Liqueur’ and ‘Among Friends’ – Petrushevksaya’s best-known and highly controversial story – and were published in Russia in 1988, 1992 and 2002 respectively. Each story is unsettling, and they are quite stylistically similar too. Despite the lulling and almost simplistic narrative voices used in There Once Lived a Mother…, the sense of foreboding is incredibly strong from the start. Atmosphere is built up marvellously through Petrushevskaya’s use of sparse wording, which gives the reader an immediate indication that something is not quite right.

In these stories, cruelty nestles into every crevice of life. The narrator of ‘The Time is Night’ is a poet named Anna, who looks after her young grandson, Tima. He is a young boy who at first appears ‘jealous’ of her ‘so-called success’, and she consequently blames him for all of the problems in her life. As the tale goes on, however, one realises that Tima is the only thing which she is living for. Her existence is bleak; her paralysed mother has been in hospital for seven years, and her son has been in prison. Her daughter, Tima’s mother, is living away with ‘baby number two’, her ‘new fatherless brat’, and taking all of the money which should be Tima’s. Anna, whilst headstrong, is rather naive, and despite her poor quality of life, there is something in her narrative which prevents any sympathy being felt for her.

The brutality and violence within There Once Lived a Mother… seem senseless after a while, making the stories rather a chore to read. The cast of characters are not quite realistic; their foibles and traits sometimes sit oddly together, and any believability is therefore diminished.

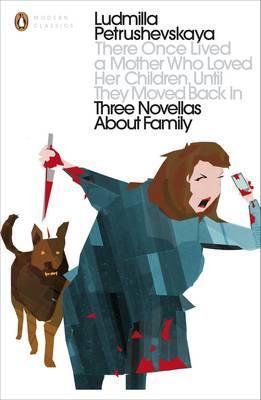

Vincent Burgeon’s cover design is striking and rather creepy, and certainly sets the tone for the words within. There Once Lived a Mother… is stark and oppressive, and whilst the tales are certainly not for the faint-hearted, Petrushevskaya does give a moderately interesting insight into a stifling regime. The novellas here are stranger than her short stories, and far more disturbing. Summers has done a good job of translating the work, but there is something oddly detached within the tales, even when the first person narrative perspective has been used. Emotion is lacking in those places which particularly need it, and whilst it is harrowing, the narrative style – particularly in the second story, ‘Chocolates and Liqueur’ – does not suit.

Purchase from The Book Depository

Advertisements Share this: