This is a blog is a part of series of 4 blogs, to read first one kindly here:

https://muhammadsalmanisrar.wordpress.com/2017/10/14/power-of-habit-notes-part-1/

STEP TWO: EXPERIMENT WITH REWARDS

Rewards are powerful because they satisfy cravings. But we’re often not conscious of the cravings that drive our behaviors. When the Febreze marketing team discovered that consumers desired a fresh scent at the end of a cleaning ritual, for example, they had found a craving that no one even knew existed. It was hiding in plain sight. Most cravings are like this: obvious in retrospect, but incredibly hard to see when we are under their sway.

To figure out which cravings are driving particular habits, it’s useful to experiment with different rewards. This might take a few days, or a week, or longer.

During that period, you shouldn’t feel any pressure to make a real change—think of yourself as a scientist in the data collection stage.

On the first day of your experiment, when you feel the urge to go to the cafeteria and buy a cookie, adjust your routine so it delivers a different reward. For instance, instead of walking to the cafeteria, go outside, walk around the block, and then go back to your desk without eating anything. The next day, go to the cafeteria and buy a donut, or a candy bar, and eat it at your desk. The next day, go to the cafeteria, buy an apple, and eat it while chatting with your friends. Then, try a cup of coffee. Then, instead of going to the cafeteria, walk over to your friend’s office and gossip for a few minutes and go back to your desk.

You get the idea. What you choose to do instead of buying a cookie isn’t important. The point is to test different hypotheses to determine which craving is driving your routine. Are you craving the cookie itself, or a break from work? If it’s the cookie, is it because you’re hungry? (In which case the apple should work just as well.) Or is it because you want the burst of energy the cookie provides? (And so the coffee should suffice.) Or are you wandering up to the cafeteria as an excuse to socialize, and the cookie is just a convenient excuse? (If so, walking to someone’s desk and gossiping for a few minutes should satisfy the urge.)

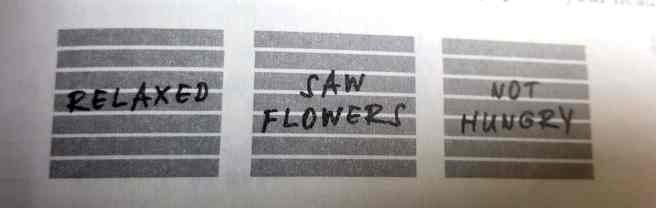

As you test four or five different rewards, you can use an old trick to look for patterns: After each activity, jot down on a piece of paper the first three things that come to mind when you get back to your desk. They can be emotions, random thoughts, reflections on how you’re feeling, or just the first three words that pop into your head.

Then, set an alarm on your watch or computer for fifteen minutes. When it goes off, ask yourself: Do you still feel the urge for that cookie?

The reason why it’s important to write down three things—even if they are meaningless words—is twofold. First, it forces a momentary awareness of what you are thinking or feeling. Just as Mandy, the nail biter in chapter 3, carried around a note card filled with hash marks to force her into awareness of her habitual urges, so writing three words forces a moment of attention. What’s more, studies show that writing down a few words helps in later recalling what you were thinking at that moment. At the end of the experiment, when you review your notes, it will be much easier to remember what you were thinking and feeling at that precise instant, because your scribbled words will trigger a wave of recollection.

And why the fifteen-minute alarm? Because the point of these tests is to determine the reward you’re craving. If, fifteen minutes after eating a donut, you still feel an urge to get up and go to the cafeteria, then your habit isn’t motivated by a sugar craving. If, after gossiping at a colleague’s desk, you still want a cookie, then the need for human contact isn’t what’s driving your behavior.

On the other hand, if fifteen minutes after chatting with a friend, you find it easy to get back to work, then you’ve identified the reward—temporary distraction and socialization—that your habit sought to satisfy.

By experimenting with different rewards, you can isolate what you are actually craving, which is essential in redesigning the habit.

Once you’ve figured out the routine and the reward, what remains is identifying the cue

To read the third blog in the series, kindly visit here:

https://muhammadsalmanisrar.wordpress.com/2017/10/14/power-of-habit-notes-part-3/

Image credits:

-Feature image: https://www.amazon.com/Power-Habit-What-Life-Business/dp/081298160X

-Images used in the blog were scanned directly from paperback..

Advertisements Share this: