George Elliott

(university essay)

This essay examines Waltz with Bashir, an Israeli animated feature-length documentary directed by Ari Folman and released in May 2008. The film follows Folman as he comes to terms – with the help of interviewees – with a lack of memories of his time as a soldier in the Israel Defense Force (IDF) during Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon, in which Israel and its Lebanese partners fought the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) and, later, Hezbollah. By the end in 1985, the war was largely regarded as Israel’s Vietnam. It was criticised as a ‘war of choice’ that lead to the rise of Hezbollah’s power in the small, fragile and diverse Mediterranean nation (Inbar, 1989). In Waltz with Bashir, the crucial gap in Folman’s memory is his specific role in the Sabra and Shatila massacre of September 1982, when more than one thousand Palestinian refugees were killed by the Christian Phalangists with the implicit support of Israel. Waltz with Bashir (shortened to Waltz herein) was released at a time when many other popular Israeli films and television series related to the country’s wars were being produced. These cultural products ignited discussion about “the Israeli psyche” and highlighted “the personal and subjective experiences of soldiers and the post-traumatic effects of the war” (Harlap, 2013, p. 167).

I take my theoretical ques on animated documentary from Anabelle Honess Roe’s work and her argument that animated documentary, “broadens and deepens the range of what we can learn from documentaries” (2011, p. 217), and has, “the capacity to represent temporally, geographically and psychologically distal aspects of life beyond the reach of live action” (2013, p. 22). I propose that animation is suitable for expressing trauma in war and the traumatised subject’s ensuing, often deferred introspection. Benefitted by a unique animated style, Waltz confronts the latent memories and dilemmas of responsibility and complicity in war. Waltz remembers war, rather than records it and simultaneously documents its own documenting. It is driven by its protagonists’ subjectivity, in the sense that it diverges from historical grand narratives shaped by interviewed leaders and experts, which belong to what Bill Nichols (1991) calls the ‘discourses of sobriety’. By advocating animation’s place in documentary, this essay highlights the epistemological problems that develop when documentary attempts to or is unable to represent war-related emotional and psychological phenomena. What people think and feel, as with war, is not readily available for the camera to capture in an indexical image. Popular documentary’s orthodox privileging of indexical live-action photography is upset by the idea of an animated documentary.

Since its release, Waltz with Bashir has been revisited extensively in academia and pop culture. It demands attention from scholars because of its disruption – like many films before it – of the ever-evolving, unstable boundaries of documentary, a project that makes unique claims to the real (Winston, 2008). Animation is a fix for something lacking in conventional documentary; namely, the subordinate position given to the imaginary, fantasy or illusory in documenting reality. What is at stake in a study of Waltz is the space in-between representing violence, memories and trauma and experiencing these complex phenomena. The tensioned rapprochement or gap between private memory and collective history is also explored in Waltz. Parallel to its animated visuals, the autobiographical narrative techniques add to this provocation.

Eleanor Kent contextualises Waltz with Bashir’s subjective drive within journalism’s relationship to the novel, a closer relationship than at first glance, as championed by the New Journalism style of Tom Wolfe and Hunter S. Thompson, which “insists on the veracity of firsthand experience over analysis by elite sources or an omniscient overview” (Kent, 2011, p. 308). Elsewhere, journalism and the graphic novel have converged in the work of Joe Sacco (2012), who has drawn his reporting on everything from The Hague to the wars in Chechnya. When not working from strict reference material, Sacco says he uses his “informed imagination” (p. x, emphasis original). As surveyed by Ricciardelli (2015), documentaries on 21st century wars have evolved to meet expectations in fulfilling marginal perspectives and differing narratives in recent decades, leaving behind attempts at pure observational modes and ‘direct cinema’ or sweeping narratives (p. 26).

Animation & documentary

Waltz with Bashir uses hand-drawing and vector-based computer technology to ‘bring to life’ stories told by Folman and his interviewees (Kraemer, 2015, p. 61). The industries and academic disciplines associated with animation see the medium as fundamentally an art of “drawing” frame-by-frame to create (not record) the illusion of movement (Furniss, 2008). Drawing has obviously taken on a broader meaning in this context, with the use of computer software, but one’s hand can still have an active role in animating (‘bringing to life’, ‘instilling with soul’), even through a digital interface (Chow Ka-nin, 2009).

Animation use has proliferated, parallel to the diffusion of the documentary genre, multimedia and development of technological capabilities. Undeniably, animation is no longer popularly perceived as strictly a medium for children’s cartoons. It is now seen as a staple of other genres and is deployed in a range of forms, many associated with flexible ideas of documentary; for example, shorts shown at film festivals or on video-hosting platforms like Vimeo, educational YouTube videos explaining philosophy and history or Amnesty International videos that provide a short visual aid for their larger campaigns. Nowhere Line: Voices from Manus Island (2015, dir. Lukas Schrank), a short animated film, which won awards at Australia’s 2016 Human Rights Arts and Film Festival, is narrated by two detainees at the controversial Australian government detention camp on Manus. The detainees’ voices and the stories they tell, recorded from a telephone interview and accompanied by subtitles, are illustrated with animation similar to Waltz’s visual style and the scenes traverse temporal and geographical boundaries. The short is an example of how animation can provide images to subjects’ testimony and have more impact for an audience. The use of animation is a solution for the inaccessibility and isolation of the detention camp. This practical substitution is used in Winsor McCay’s 1918 The Sinking of the Lusitania, often considered the first animated documentary, which simulated a newspaper-esque aesthetic to show the passenger liner sinking after being struck by a German torpedo (Honess Roe, 2011, p. 218). In the same manner as Nowhere Line, news media and NGOs have used animation to add a ‘human story’ to ground unfathomable current affairs. For example, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists released an animated video that told the story of the “real victims” of wars and corruption being fueled by the money laundering exposed in the so-called Panama Papers scandal (ICIJ, 2016, April 3). For the most part, the animation in these videos resembles that which would have been seen had it been captured by a photographic apparatus and they are intently framed as such.

Animation commonly acts as a practical memetic substitution for that which photography is not able to capture, as is the case with Nowhere Line. Beyond this, however, animation can portray something that photography cannot or, at least, something that can by-pass photography. One straightforward popular example of this would be maps, which were used heavily in World War Two newsreels to show where the different fronts and assaults were taking place, using striking arrows and contrasting blocks of colour that pit “dark hues for enemy nations against paler colours for the Allies” (Honess Roe, 2011, p. 220). More recently, arrows have made a comeback in denoting mass migration flows and animated maps of warzones in Syria and Iraq, with different coloured overlays – often fluid, moving according to a video’s time-stamp – representing the many belligerent actors, now feature heavily in news media videos (for example, Vox, 2017, April 7; 2017, June 12). These are more than static graphics in that they involve and often rely on moving components.

These instances, based on abstract or symbolic concepts (diagrams and maps) are unambiguously different to the animation substitutions that replace the photo with a frame-by-frame simulation of the moving image and the photographic apparatus’ technique (framing, panning, zooming). What is important for interpreting Waltz’s animation is to look beyond the two modes demonstrated by Nowhere Line and Vox’s graphics of Syria. Animation has the potential to add to or expand on the documentary project; beyond either a practical mimetic remedy or the imposing demarcations of maps. This is the position of Honess Roe (2011; 2013), who develops a framework for studying animated documentary. She positions animation’s potential to go beyond substitution as a core pillar in the conceptualisation of animated documentary:

Ancient history, distant planets and forgotten memories are just some of the unseeable aspects of reality that animation manifests for the documentary viewer. However, animation goes beyond just visualizing unfilmable events. It invites us to imagine, to put something of ourselves into what we see on screen, to make connections between non-realist images and reality (2011, p. 217, emphasis added).

Honess Roe dismisses attempts to shoehorn animated documentary into Bill Nichols’ modes of documentary or create new self-serving categorisations for animated documentaries (2011, p. 223–225). In line with Nichols’ modes (2001), Del Gaudio (1997) considers animated documentary as reflexive whereas Strøm (2003) leans more towards a performative classification. Questioning the utility of these two oft-cited interpretations, Honess Roe (2011) suggests our theoretical starting point should be to ask, “what is the animation doing that the conventional alternative could not” (p. 225)? She introduces three key functions of animated documentary to approach this question: mimetic substitution, non-mimetic substitution and evocation. Identifying and observing these three functions, which are not mutually exclusive, will lead to an understanding about how animated documentary works in its “capacity to enhance and extend” the transmission of knowledge and meaning (p. 225).

Waltz’s aesthetics & motifs

Other animated documentaries strive for increasing levels of verisimilitude and simulate the cinematography of live-action images to create a mise-en-scene that audiences will find familiar. Close mimesis is subsequently intertextually read in accordance with a ‘stock’ of images in the audiences’ mind (Viljeon, 2014, p. 47). Landesman and Bendor (2011) outline why animation presents such an essential opposition to this ‘stock’ reading, where the viewer’s interpretation of the indexical image is in reference not only to its referential objects, but other stock images like it:

This relationship is one that moves away from faith – having faith in the image because it represents reality with photographic indexicality – to trust – trusting the documentary text to be making truth claims that reflect the world in sophisticated ways (p. 254).

Waltz straddles Honess Roe’s mimetic and non-mimetic substitution functions. By moving away from attempts to create the illusion of a filmed image, Honess Roe (2011) says, a non-mimetic approach acknowledges “animation as a medium in its own right, a medium that has the potential to express meaning through its aesthetic realization” (p. 226). However, there is no hard line between mimetic and non-mimetic but they are on a spectrum. For example, Nowhere Line’s backgrounds are close to what would have been captured with a camera but it takes more liberalities in drawing the human form.

On this mimetic scale, it is often colour, shading and lighting that are emphasised and distorted. Silhouettes and big blocks of black or colour are prominent in Waltz. Some of the most memorable scenes are comprised of a sepia chiaroscuro, with the visual hierarchy structured on the light and dark of the image. Both day and night scenes are coloured with a principle palette of blues, greys and yellows. The boldness means that the film is not received as ‘twitchy’, like Richard Linklater’s A Scanner Darkly (2006) or Waking Life (2001), which use a sketchy rotoscoping, a technique that is often mistakenly identified in Waltz.

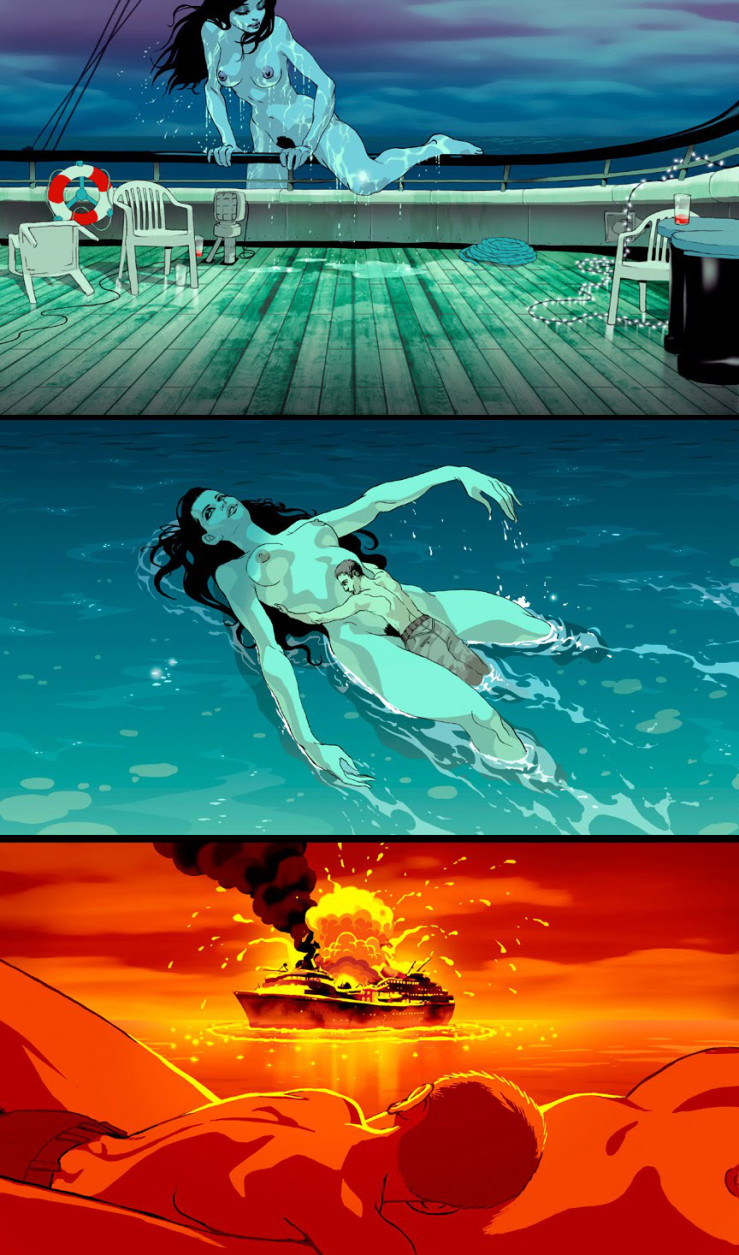

Chow Ka-nin (2009) points to “movement” as central to animation’s “spirit”. In his conceptualising of the phenomenological machine-human threshold, he identifies pieces of animation on a continuum of “liveliness”; from mechanical Disney “character animation” to the avant-garde forms of Len Lye (p. 79–80). The flat two-dimensional impression of animation, where one feels that the characters might flutter off the screen like a leaf, is avoided in the slow movements of Waltz’s characters, which add a sense of volume. The characters’ gait evokes the act of wading through water. As Honess Roe (2013) points out, water and the sea is a central motif in Waltz and in dreams generally (p. 162–163). Two of Folman’s interviewees, as well as Folman himself, narrate flashbacks or dreams where the ocean is itself a prominent character. In a psychoanalytical analysis, Baer (2013) says the “aquatic images clearly evoke birth and maternity” (p. 101). In one of the more visually memorable stories, and one that reflects the film’s comments on masculinity’s determinant (or blinding) posture in war, Folman’s friend Carmi describes a dream in which he is taken away from a boat he was travelling to the war on by a larger-than-life female. Carmi lies on the woman’s stomach (near the womb), being carried away, and watches as the boat is bombed and his comrades die. The animation illustrates the woman’s maternal love in her unspoken, slow but insistent movements onto the boat to get Carmi and her effortless, quiet backstroke glide through the water. For Baer (2013), this dream evokes the discourses of diaspora and exodus that continue to be found in Jewish and Israeli literature and culture (p. 102).

At the beginning of the film, Folman’s friend, Boaz, tells him about nightmares where dogs vengefully run after him, which Boaz reveals are the exact number of dogs that he killed during night operations in Lebanon. The conversation between Folman and Boaz sparks Folman’s remembering or ‘disremembering’ of events in Lebanon and, therefore, the film project itself. Folman explains, through voice-over narration, that the night after that conversation he starts having dreams about the war, a war he realises he has little to no memory of. This first dream becomes the main dream sequence in Waltz, being shown three times. In the first iteration, Folman, standing on a Tel Aviv esplanade, suddenly turns his head down the coast to find flares hanging in the sky. The city is no longer modern and Israeli, but has become war torn and Lebanese. Not only is Folman transported back to West Beriut, but we, the viewer, also seamlessly pass into a dream space with him. This is an example of how the films narratives positions dream space and ‘real’ space as hierarchically equal. While Folman is still in the water, there is a point-of-view shot, one of only two in the entire film. What the animation evokes for me here is the leaving of the womb’s comfort and the unhurried march towards the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps, the nexus of Folman’s disremembering. The flare’s yellow illuminates the subjects and urban landscape as Folman and two of his comrades rise naked out of the ocean, put their uniforms on and enter Beriut’s crumbling heart of darkness. Parallel to water, flares play a multifunctional role in Waltz. They hang in the sky, illuminating several scenes throughout the film and contributing to the yellow palette; as Stewart puts it, the “animators have found just the right sulfuric glow for the delirium” (2010, p. 58). The flares also hang heavily on Folman’s mind because they are a symbol and instrument of Folman’s participation in the massacre of the Palestinian families. It was later established through investigations – and this is what Folman comes to terms with – that the IDF had knowledge of and effectively facilitated the atrocity. By September 1982, the Israel and its Lebanese allies had won the siege of West Beriut and the IDF had deployed a sophisticated occupying force, with adequate communications capabilities. The Bashir in Waltz with Bashir, Lebanon’s Christian President-elect, Bashir Gemayel, had been assassinated by a militant loyal to a Syria-aligned group, resulting in energised religio-nationalist anger from the Phalangists (Fisk, 2012). Israel’s then-Minister of Defence, Ariel Sharon, who is depicted in Waltz, implicitly supported the Phalangists decision to enter the camps and the IDF facilitated the militia’s by setting up checkpoints, directing traffic, closing camp entrances and firing off flares (Shahid, 2002).

Waltz is not just overcoming a limitation creatively but also evoking something:

By visualizing these invisible aspects of life, often in an abstract or symbolic style, animation that functions in this evocative way allows us to imagine the world from someone else’s perspective (Honess Roe, 2011, p. 227).

Waltz with Bashir’s aesthetic and motifs convey “internal worlds” (p. 228) that are not readily available for conventional live-action documentary. The unique art style in Waltz transmits a feeling of the surreal, which is, “inexact, splintered, uncertain, incongruent and surprising” (Viljeon, 2014, p. 43).

Violence, trauma & memory

‘Dreamlike’ has been used elsewhere in studies on the conjuncture of traumatic experience and the excess or stock of ‘baked in’ indexical images (Paget, 2015). Of course, 9/11 is the ultimate case of this excess. The events themselves were immediately repeated, with, “countless television replays of the event occurring in what normally would be the space and time of the real”, and no deferral was possible (Saltzman & Rosenberg, 2006). Sobchack (2004) takes a similar stance on the Zapruder footage of JFK’s assassination: “Rituals of repetition and stop motion, of closer and closer scrutiny, yield only greater and greater mystification” (p. 253). While the JFK assassination and 9/11 are remembered by their event’s literal impacts repeated ad infinitum, Folman’s time in Lebanon is remembered as a deferred ‘dreamlike’ lack. There is an absence of material and mental images because of a ‘failure’ to see. Cathy Caruth (1996), a theorist of literature and trauma, explains that,

Traumatic experience, beyond the psychological dimension of suffering it involves, suggests a certain paradox: that the most direct seeing of a violent event may occur as an absolute inability to know it; that immediacy, paradoxically, may take the form of belatedness (p. 91–92).

Waltz is as much “a meta-analysis of the process of representation”, memory and trauma as it is about the Historical Eventness of the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon (Viljeon, 2014, p. 47). Visually, it succeeds in conveying the upsetting and horrific results of Israel’s support for the Christian militia, the Phalangists. Though, it also succeeds in documenting how there is not a simple causal line between the referent and its sign and “fantasy and the unconscious play a crucial role in the formation of the traumatic historical past” (Yosef, 2010, p. 318). Instead of trying to accurately account for the Other’s suffering or attempt to measure who the ‘real’ victims of a war are, as conventional archival and expert interview documentary may do, Waltz’s takes on an “ethical stance that falls outside of the victim/perpetrator dyad” (Hochberg, 2013, p. 50). Writing on Holocaust documentaries that subvert the genre’s norms, Williams (1993) posits the “success” in such a project,

[…] is the ability not only to assign guilt in the past, to reveal and fix a truth of the day-to-day operation of the machinery of extermination, but also to deepen the understanding of the many ways in which the Holocaust continues to live in the present (p. 18, emphasis added).

Hochberg (2013) argues that Waltz’s ethical stance is a response to the traumatic component of the ‘not seeing on time’ process that Freud and Lacan theorized (p.45–46), where the experience of the traumatic event is differed to later imaginations rather than the event itself and, therefore, it lives on, embroiled in the minds of Folman and his comrades and the national psyche. This, we can juxtapose with the aforementioned media-saturation paradigm concerning 9/11, where the traumatic event was immediately and repeatedly imaged. The precession of those instant 9/11 images thereafter holds a monopoly – a pre-mediating shadow – over any belated revisiting of the trauma. One of Folman’s friends, interviewed throughout the film, asks, “Can’t films be therapeutic?” The production of Waltz in itself initiated a process of remembering through others’ remembering (Viljeon, 2014, p. 41). Folman, Yosef (2010) states,

[…] constructs the film as a kind of lieu de mémoire [site of memory] that preserves repressed traumatic events that have been denied entry into the nation’s historical narrative (p. 316).

This process becomes an act of multi-levelled reenactment or recreation, “where the omniscience of dogmatic fact is shaken by the ephemerality resulting from the reprocessing of the events” (Kraemer, 2015, p. 60; see also Nichols, 2008).

*

This essay has highlighted how Waltz with Bashir’s animation and narrative, as codependent virtues, presents a psychical expressionism that would be unsuitable and difficult for conventional live-action documentary to capture. Despite its ‘subjectivity’ and subversive medium, Waltz is readily understood as creatively documenting a truth of the world, well in line with the broad directions sketched out by early documentarians. Folman’s confrontation with the stubborn phantasmagoria of trauma is animated (‘endowed with spirit’) by playing with the space in-between representing and experiencing. Folman’s introspective process becomes the driving force of the narrative. Following one of Sobchack’s (1999) chief hypothesis that documentary is less a ““thing” than “an experience”” (p. 241), the viewer’s bond with the documentary fundamentally shifts. Whereas there was “faith” in the indexical image of live-action documentary, the viewer of Waltz meaningfully experiences an ethical determination of “trusting” the animated image. The phenomenological, contextual fabric of the world – woven by ‘the actual and the fantastic, the real and imagined’ – is explored more comprehensively when psycho-emotional aspects can be evoked (Landesman & Bendor, 2011).

In line with Honess Roe’s theory, animation allows documentary to show the ‘distal’ aspects of life that live-action documentary cannot capture and expands documentary’s capacity to teach us something or make us understand something about (a subject in) the world. Waltz with Bashir does not explicitly cover the political issues of the invasion of Lebanon and subsequent wars or give us a linear timeline of events, with voiceovers and God-like narration noting, for example, the quantities of killing-machines involved in a given battle. Instead, Waltz seeks to document one man’s crisis with memory and trauma. Indeed, in doing so, the film acts as a microcosm for developments in a country’s conception of its History and its existential identity, values that are always tied to war. Ari Folman’s animated documentary demonstrates that animation can undoubtedly evoke hallucinations, dreams, flashbacks and nightmares and in the process, expand documentary’s epistemological boundaries.

References

Baer, N. (2013). “Can’t Films Be Therapeutic?” Cinema, Psychoanalysis, and Zionism in Ari Folman’s Waltz with Bashir. In E. Arapoglou, M. Fodor, & J. Nyman (Eds.), Mobile Narratives: Travel, Migration, and Transculturation (pp. 97–110). New York, US: Routledge.

Caruth, C. (1996). Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, Narrative, and History. Baltimore, US: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Chow Ka-nin, K. (2009). The Spiritual-Functional Loop: Animation Redefined in the Digital Age. Animation: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 4 (1), 77–89.

Del Gaudio, S. (1997). If Truth Be Told Can ‘toons Tell It? Documentary and Animation. Film History, 9 (2), 189–199.

Fisk, R. (2012, September 14). The forgotten massacre. The Independent. Retrieved from http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/the-forgotten-massacre-8139930.html

Furniss, M. (2008). The Animation Bible: A Pratical Guide to the Art of Animating, from flipbooks to Flash. New York, US: Abrams.

Harlap, I. (2013). Serial Trauma: Seriality and Post-Trauma in the Israeli Television Drama Parashat Ha-Shavu’a. Jewish Film & New Media: An International Journal, 1 (2), 166–189.

Hochberg, G. (2013). Soldiers as filmmakers: on the prospect of ‘shooting war’ and the question of ethical spectatorship. Screen, 54 (1), 44–61.

Honess Roe, A. (2011). Absence, Excess and Epistemological Expansion: Towards a Framework for the Study of Animated Documentary. Animation: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 6 (3), 215–230.

Honess Roe, A. (2013). Animated Documentary. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Inbar, E. (1989). The ‘no choice war’ debate in Israel. Journal of Strategic Studies, 12 (1), 22–37.

Kent, E. (2011). Perpetration, Guilt and Cross-Genre Representation in Ari Folman’s Waltz with Bashir. Holocaust Studies: A Journal of Culture and History, 17 (2–3), 305–329.

Kraemer, J. A. (2015). Waltz with Bashir (2008): Trauma and Representation in the Animated Documentary. Journal of Film and Video, 67 (3), 57–68.

Landesman, O., & Bendor, R. (2011). Animated Recollection and Spectatorial Experience in Waltz with Bashir. Animation: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 6 (3), 353–370.

Nichols, B. (1991). Representing Reality. Bloomington, US: Indiana University Press.

Nichols, B. (2001). Introduction to Documentary. Bloomington, US: Indiana University Press.

Nichols, B. (2008). Documentary Reenactment and the Fantasmatic Subject. Critical Inquiry, 35 (1), 72–89.

Paget, D. (2015). Ways of showing, ways of telling television and 9/11. In S. Lacey, & D. Paget (Eds.), The War on Terror: Post-9/11 television drama, docudrama and documentary (pp. 11–32). Cardiff, UK: University of Wales Press.

Ricciardelli, L. (2015). American Documentary Filmmaking in the Digital Age: Depictions of War in Burns, Moore, and Morris. New York, US: Routledge.

Sacco, J. (2012). Journalism. London, UK: Jonathan Cape.

Saltzman, L., & Rosenberg, E. M. (2006). Epilogue. In L. Saltzman, & E. M. Rosenberg (Eds.), Trauma and Visuality in Modernity (pp. 272–275). Hanover, US: Dartmouth College Press.

Shahid, L. (2002). The Sabra and Shatila Massacres: Eye-Witness Reports. Journal of Palestine Studies, 32 (1), 36–58.

Sobchack, V. (1999). Toward a phenomenology of non-fictional film experience. In J. M. Gaines, & M. Renov (Eds.), Collecting Visible Evidence (pp. 241–254). Minneapolis, US: University of Minnesota Press.

Sobchack, V. (2004). Carnal Thoughts: Embodiment and Moving Image Culture. Berkley, US: University of California Press.

Stewart, G. (2010). Screen memory in Waltz with Bashir. Film Quarterly, 63(3), 58–62.

Strøm, G. (2003). The Animated Documentary. Animation Journal, 11, 46–63.

Viljoen, J-M. (2014). Waltz with Bashir: between representation and experience. Critical Arts: South-North Cultural and Media Studies, 28 (1), 40–50.

Williams, L. (1993). Mirrors without Memories: Truth, History, and the New Documentary. Film Quarterly, 46 (3), 9–21.

Winston, B. (2008). Claiming the Real II: Documentary – Grierson and Beyond. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Yosef, R. (2010). War fantasies: Memory, trauma and ethics in Ari Folman’s Waltz with Bashir. Journal of Modern Jewish Studies, 9 (3), 311–326.

Filmography

Folman, A. (Director & Producer). (2008). Waltz with Bashir. Israel: Bridgit Folman Film Gang.

ICIJ. (2016, April 3). The Panama Papers: Victims of Offshore [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/F6XnH_OnpO0

Linklater, R. (Director). (2001). Waking Life. USA: Thousand Words.

Linklater, R. (Director). (2006). A Scanner Darkly. USA: Thousand Words.

Schrank, L. (Director & Producer). (2015). Nowhere Line: Voices from Manus Island [Short motion picture/video file]. Australia: Studio Pancho. Retrieved from https://vimeo.com/167361538

Vox. (2017, April 7). Syria’s war: Who is fighting and why [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/JFpanWNgfQY

Vox. (2017, June 12). The 4 man-made famines threatening 20 million people [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/CvSW5Ez0koM

Advertisements Share this: