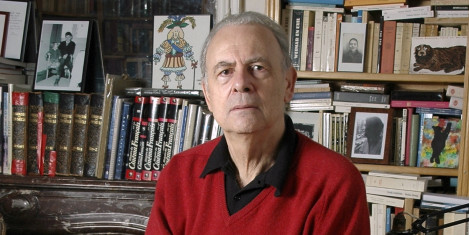

Arthur Llewelyn Jones-Machen was born in Caerleon, Wales in March of 1863 to the Anglican clergyman John Edward Jones and his wife, Janet. The shortened form of Machen, which Arthur used for most of his life, was a surname from his mother’s side of the family. He grew up in Llanddewi Fach, a rural parish outside of Caerleon, where his father was vicar. The area had a rich history intertwined with Welsh myth and folklore. The earliest legends of King Arthur placed the seat of his kingdom not in Camelot but in Caerleon. The landscape would influence Machen’s future work in fantasy and weird fiction.

In the 1870s, archaeologists began to uncover remnants of Roman settlements in the region: stonework and pagan idols. Machen’s own grandfather, who had been the vicar of Caerleon, was a well-regarded local antiquary, who had discovered Roman stones in his own churchyard. The sense that strangeness and the supernatural permeated the very land would remain with Machen. That countryside with its Roman ruins and fairy glens would reoccur often in his fiction. Much later, he would write:

I shall always esteem it as the greatest piece of fortune that has fallen to me, that I was born in that noble, fallen Caerleon-on-Usk, in the heart of Gwent. . . . For the older I grow the more firmly I am convinced that anything which I may have accomplished in literature is due to the fact that when my eyes were first opened in earliest childhood they had before them the vision of an enchanted land.

As a boy, Machen was intelligent, reserved, and solitary. Fred Hando, in his volume of local history, The Pleasant Land of Gwent, attributes Machen’s interest in the occult in part to an article about alchemy that he read in Charles Dickens’s magazine, Household Words, when he was eight years old. Hando elaborates on Machen’s youthful reading habits: “He bought De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium Eater at Pontypool Road Railway Station, The Arabian Nights at Hereford Railway Station, and borrowed Don Quixote from Mrs. Gwyn, of Llanfrechfa Rectory. In his father’s library he found also the Waverley Novels, a three-volume edition of the Glossary of Gothic Architecture, and an early volume of Tennyson.” By the time he was sent to study at Hereford Cathedral School at the age of eleven, he showed an interest in history and literature. His family might have sent him on to Oxford, where his father had studied, but they lacked the resources. Instead, he decided to pursue a career in journalism.

Machen moved to London in the early 1880s. He did not immediately attempt to establish himself in Fleet Street, instead living on little and spending his time alone, wandering the huge city, observing the strange juxtaposition of old and new, as Victorian buildings encroached upon the often dilapidated remains of ancient London. In his isolation, in the midst of the city’s noise and bustle, he wrote.

In 1881 he published Eleusinia, a poetic treatment of the Greco-Roman mystery cult. He published his second book, The Anatomy of Tobacco, in 1884. Through his publisher, George Redway, Machen was hired as an editor at the magazine Walford’s Antiquarian. During this period he undertook several translations from French literature, including a multi-volume edition of Casanova’s Memoirs, and produced his first novel, The Chronicle of Clemendy.

In 1887, at the age of twenty-four, Machen married a young music teacher named Amy Hogg. His father died the same year, leaving him an inheritance that allowed Machen to write full time. He began to develop a more contemporary style. His fiction became fantastic, leaning towards gothic themes and horror. His first major achievement in this new style was a short novel, The Great God Pan, for which he is still best known. The story, about a woman born of pagan ritual and occult science, caused a stir with its sense of grotesquerie and perverse sexuality. The Great God Pan was published by John Lane as part of the “Keynotes” series. It marked Machen’s arrival as a member of the literary Decadent movement. He became acquainted with other major figures of the genre, including Oscar Wilde and Aubrey Beardsley. He and Amy were living in a cottage in the Chilterns in southeast England. There he wrote another book, The Three Imposters, which was also published by Lane. It is a portmanteau novel which follows two bohemian friends as they try to learn the identity of a young man in spectacles who was seen throwing a Roman coin—”the gold Tiberius”—into the street as he ran terrified into the night. Along the way they hear many strange stories.

Machen’s rise in the literary world was cut short by circumstances outside of his control. The Decadent Movement fell from popularity in the mid-1890s when Oscar Wilde was put on trial for sodomy and gross indecency. Machen continued to write over the next decade but did not publish. Fortunately, he still had his inheritance and royalties to live on. He wrote two novellas, The White People and A Fragment of Life, both of which evoked the mystical Welsh countryside of his childhood, as well as a novel, The Hill of Dreams during this period. He also wrote a series of prose poems, which were later collected in Ornaments of Jade. In addition to writing, Machen took an editorial position at the magazine, Literature, in 1898. Though he did not remain at the job for long, it turned his attention toward literary theory, allowing him to develop his own ideas on the subject, which he outlined in the book, Hieroglyphics, which was published in 1902.

As the turn of the twentieth century approached, Machen suffered a terrible loss. After a long illness, his wife, Amy, died of cancer in 1899. Machen was overwhelmed with grief and suffered a nervous breakdown. Friends encouraged him to recover by cultivating his spiritual life. Through Arthur Edward Waite, he joined the occult society, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Though Machen shared the group’s interest in the esoteric his own spiritual awakening was leading him in different direction.

Machen was a lifelong Anglican Christian. He had never left the faith in which he was raised, but following the death of his wife, he began to experience a blossoming of religious epiphany. He would later write that during the “autumn of 1899-1900 . . . the two worlds of sense and spirit were admirably and wonderfully mingled, so that it was difficult, or rather impossible, to distinguish the outward and sensible glow from the inward and spiritual grace.” He was a high churchman who favored the catholic inheritance of the Church of England over the reformed inheritance. But he identified the catholicity of Anglicanism with a Celtic Christianity that predated the arrival of missionaries from the Church of Rome.

He found other ways to work through the heartbreak of Amy’s death as well. In 1901, he made the perhaps unexpected—but to anyone who knows the healing potential of theater, not surprising—decision to become an actor. He joined Frederick Benson’s theater company. Touring and performing gave Machen something to be excited about, and the change began to spill into the rest of his life. Though previously extremely reserved, he now began to become more outgoing and gregarious.

Four years after Amy’s death, Machen married for the second time, to Dorothie Purefoy Hudleston. Purefoy, as she was called, was a fellow member of Benson’s company. The couple frequently toured with the troupe and enjoyed a rather bohemian lifestyle. Purefoy encouraged Machen in both his faith and his writing. In 1906, at last, he published a collection of old and new pieces, The House of Souls. The following year, he published the novel he had written in the 1890s, a masterwork of literary Decadence, The Hill of Dreams. However, the times had changed, as had Machen himself. He considered it his purpose as a writer to oppose materialism and promote spiritual and mystical values. This led him to largely abandon the themes of paganism and evil that had characterized his works of the fin de siècle.

A marked new dimension appears in his writings from the early 1900s onward. His interest in Celtic Christianity and mysticism came to define his work. He began to write for The Academy, a High Anglican literary journal, run by Lord Alfred Douglas, in which Machen explored the legends of King Arthur and the Holy Grail, placing them in the context of Celtic Christianity. Machen’s writings on religion emphasized ritual and the imagination. During this time, he translated his interest in the Holy Grail to fiction in the novel, The Secret Glory, about a young orphan who achieves salvation and martyrdom on a quest for the Grail.

Toward the end of the decade, Machen ran into financial difficulties as his legacies ended and his funds from acting and occasional publishing proved insufficient. To make ends meet, he returned to his career in journalism. He joined the staff of the Daily Mail in 1908 then transferred to The Evening News in 1910. As an experienced writer, he was asked to report on a variety of important subjects, including the funeral of renowned explorer Captain Robert Falcon Scott. Most of his regular pieces, however, focused on religion or on the arts. Though The Evening News offered Machen a good, reliable income, he chaffed at the constraints of full-time employment.

Despite his dissatisfaction with the job, it gave him his first real taste of fame. In August of 1914, at the outset of the First World War, the British and German armies fought at Mons in Belgium. The battle ended in a strategic retreat by the British, a demoralizing opening to the war. Machen responded with a newspaper story that combined fiction and fact, imagining that angelic archers had appeared over the battlefield and fought alongside the British. This piece, “The Bowmen,” soon caused mass confusion. Machen’s previous stories for the paper had not included fiction, and the piece resembled the first-person accounts of soldiers frequently published by The Evening News. On top of this, censorship from the battlefield made it difficult for those at home to know exactly what had really taken place at the front. Many people believed that the story was true. Machen always maintained that it was a fiction. Nevertheless, the story of the “the Angels of Mons” spread and became legendary, with soldiers confirming that they had seen the vision with their own eyes, and readers refusing to believe that Machen had made it all up.

The story was published in a collection of wartime fiction, which sold very well. Machen turned his attention back to his own writing, publishing a number of new stories. The relative financial security that he enjoyed at this point helped support a growing family. He and his wife were blessed with two children during the 1910s. But his career in journalism ended abruptly in a bizarre episode in 1921. That year he published an obituary of his former editor at The Academy, Lord Alfred Douglas. In the obituary he alluded to the homosexual affair between Lord Alfred and Oscar Wilde, which had been the cause of Wilde’s trial and disgrace. Awkwardly for Machen, Lord Alfred was had not died. He sued The Evening News. Machen was fired. He responded to his exile from Fleet Street with a quotation from the Psalms in Latin: “Eduxit me de lacu miseriae, et de luto faecis” (“He brought me up also out of an horrible pit, out of the miry clay,” in the King James Version). One has to wonder whether he sabotaged his own career intentionally, or at least subconsciously.

Machen saw a resurgence in popularity of his early fiction as the 1920s began. His horror stories had been discovered in the United States. This led to a reappraisal of his work in Britain. He was frequently republished on both sides of the Atlantic throughout the decade. During the 1920s the Machens lived in St John’s Wood where their house was the center of a literary salon and many parties. In the 1930s Arthur and Purefoy moved out of London, retiring to Amersham in Buckinghamshire, where they lived quietly and peacefully until Machen’s death in 1947.

The importance of Arthur Machen and the range of his influence cannot be overestimated. Every significant writer of weird fiction in the twentieth century has been directly inspired by him. H.P. Lovecraft considered him one of the very few “modern masters” of the genre. As a Christian thinker he had a profound influence on the Anglican mystic Evelyn Underhill. His book, The Secret Glory, read as a teenager, inspired the Christian faith of Sir John Betjeman.

“Here then is the pattern in my carpet,” Machen once wrote, “the sense of the eternal mysteries, the eternal beauty hidden beneath the crust of common and commonplace things; hidden and yet burning and glowing continually if you care to look with purged eyes.”

See also: The Only Known Recording of Arthur Machen

Sources:

Hando, Fred. (1945) The Pleasant Land of Gwent. Newport: R H Johns Ltd.

Machen, Arthur. (1923) The Works of Arthur Machen (Caerleon Edition). London: Martin Secker.

Machen, Arthur. (1924) The London Adventure, or The Art of Wandering. London: Martin Secker.

Sweetster, Wesley; Goldstone, Adrian. (1960) Arthur Machen. Llandeilo: St Albert’s Press.

Valentine, Mark. (1995) Arthur Machen. Bridgend: Seren Books.

Wilson, A.N. (June 6, 2005) “Angels were on his side,” The Telegraph. London. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/comment/personal-view/3617433/World-of-books.html

“The Life of Arthur Machen.” http://www.arthurmachen.org.uk/machbiog.html

Share this: