“I was about to tell her that Miralles hadn’t fought in one war, but many, but I couldn’t, because I suddenly saw Miralles walking across the Libyan desert towards the Murzuk oasis — young, ragged, dusty and annonymous, carrying the tricolour flag of a country not his own, of a country that is all countries and also the country of liberty and which only exists because he and four Moors and a black guy are raising that flag as they keep walking onwards, onwards, ever onwards.”

I love this book. I only read it relatively recently, at the nagging reminders of He Judges (ta love) and adored its introspective, meandering blend of history, fiction, biography and autobiography. I found the movie by accident, on what must be about the 50th trip to Diego Luna’s imdb page. My repeated ignoring of it must have been down to the slightly different place-name (I read it in translation as Soldiers of Salamis), and to the fact that the author, Javier Cercas, becomes Lola Cercas in this movie adaptation. And it’s also quite expensive still on Amazon; lucky, then, that I work in a city with more world-class libraries than you can shake a stick at.

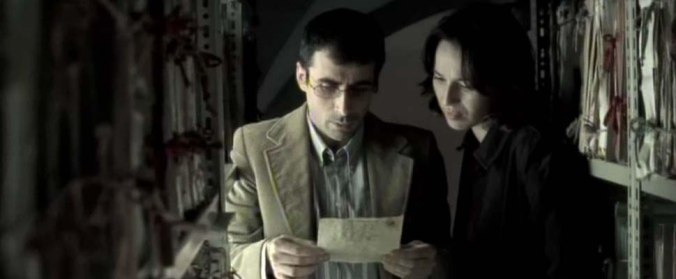

It’s a strange story to adapt: it’s the story of how a journalistic investigation hits a dead-end and slides into wishful thinking and unanswerable questions, told through the self-doubting lens of the author, a one-time novelist who’s been bereft of inspiration for years. But the movie does an amazing job of adapting its source, contriving situations that allow for all the historical exposition in the book, and retaining a good deal of its humour, not least that which comes at Cercas’ expense.

In the first half of the movie, Lola thinks she’s conducting a serious investigation into facts from the Spanish Civil War — tracing the steps that led to the fascist writer, Sánchez Mazas, surviving a mass execution on the Spanish/French border, and returning to serve Franco with the help of his ‘Forest Friends’ and some Catalan farmers. The movie uses documentary footage, real and expertly mimicked, plus flashbacks featuring Ramon Fontserè as Sánchez Mazas, to show the narrative in all its detail. Most effective of all is the way in which Lola’s discussions with the old survivors are filmed: the camera focuses on the men’s faces, and the outside light washes the colours thin, giving the impression of documentary filming, whilst Lola quietly prompts them from the edge of the shot. There is far less of this on show in the second half of the movie, where Lola looks for a hero, a heart for the story of the cold fascist’s survival, trying instead to identify the man who spared him in a clearing in the forest just outside Collel. In this part, it is just one or two flashbacks that are returned to again and again: the vivid, romantic image of the soldier dancing his paso doble in the rain, and his dark-eyed, enigmatic, happy expression as he decides to spare Sánchez Mazas.

Joaquín Notario does not look anything like how I imagined the soldier in the forest. But he’s perfect. The movie lingers and returns to his wondering, open expression again and again and rightly so; if you don’t get that shot right you lose so much of the story’s beating, intangible heart. Similarly, Joan Dalmau looks not a jot like my imagined Miralles, but he’s wonderful nonetheless. He Judges and I were alternately cackling loudly and sitting in stunned silence as he slipped between observations on the present and on the past. Although a lot of detail had to be culled from Miralles’ memories, the effect was still profound, even without that closing narrative meander that I love in the book, where Cercas imagines dancing the paso doble ‘Sighing for Spain’ with Sister Françoise on Miralles’ grave, watched by Conchi and Bolaño.

The latter doesn’t make it into the movie at all, but oh boy, Conchi sure does. She gradually comes into her own in the book; Cercas’ first relationship since his divorce, someone who seems strange and unrelatable to him, even as he takes solace in the physical side of their partnership, yet whose feedback and pushy support keep Cercas on track to complete the novel. She’s a blend of brash overconfidence and brittle fears, and she bursts to life in the movie in María Botto’s hands, the character barely altered despite the fact that Javier has become Lola. The scenes between Lola and Conchi are easily the best of the scenes set in contemporary Spain (barring Miralles’ interview perhaps), but rather than have them in an established relationship, here it’s about Conchi’s unrequited lust/love for Lola. It does a good job of allowing the movie to show Lola’s emotional distance, but feels like a bit of a cop-out in some ways, too; not least because it then shoehorns in a quick snog between Lola and young Gastón, the Mexican exchange student, to prove that Lola likes men, no, honest guv, she does! I wonder if Diego Luna felt he was being typecast after Y tú mamá también? Can’t imagine he’d mind much, if so…

Ariadna Gil holds the whole movie together, despite the historical male figures threatening to make it only about them. She’s a delightful klutz, constantly dropping things, fixing a hole in her pocket with a stapler, falling asleep at the keyboard with her glasses on, and it’s always great to see a female character who’s this clumsy, and who gets to remain emotionally aloof rather than becoming some sort of cutesy ditz who just needs a sexy guy to carry her stuff for her (not for lack of Gastón’s trying). She’s as frustrating as she should be, single-minded about her search for the man who spared Sánchez Mazas, even when Miralles is telling her far more interesting stories from his own life and those of his long-dead friends.

More so than the book, the movie shows how prickly mentioning the Civil War still was (is!) in Spain. Cercas struggles to identify the precise nature of the humanity he’s looking for at the heart of his story: the mass execution is wrong, regardless of its victims’ repellent political beliefs, so it’s good that Sánchez Mazas doesn’t become just another body in the mud in that clearing. But what does he go on to do? We know he remains loyal enough to his Forest Friends to order the release of a son of one of them from jail, but he’s still an influential part of the fascist dictatorship. The soldier who spared him is a naïf, a romantic child caught dancing in the rain rather than guarding his prisoners, and Miralles is a hardened fighter, troubled by the loss of so many friends, and no longer at home in Spain at all. It’s up to Cercas, listening to figures from all sides, drawing out the individual, human stories, and telling Miralles that he will not be forgotten, to blend this awkward cocktail of all-too-recent memories into a story of both hopelessness and hope.

Advertisements Share this:And then I’d take Sister Françoise by the hand and ask her to dance with me besides Miralles’ grave, I’d insist that she dance to a music she didn’t know how to dance to on Miralles’ fresh grave, in secret, so no one would see us – so no one in Dijon or in France or in Spain or in all of Europe would know that a good-looking, clever nun (with whom Miralles always wanted to dance a paso doble and whose bum he never dared touch) and a provincial journalist were dancing in an anonymous cemetery of a melancholy city beside the grave of an old Catalan Communist, no one would know except a non-believing and maternal fortune-teller and a Chilean lost in Europe who would be smoking, his eyes clouded, standing back a little and very serious, watching us dance a paso doble beside Miralles’ grave just as one night years before he’d seen Miralles and Luz dance to another paso doble under the awning of a trailer in the Estrella de Mar campsite, seeing it and wondering if maybe that paso doble and this one were in fact the same, wondering without expecting an answer, because he already knew that the only answer is that there is no answer, the only answer is a sort of secret or unfathomable joy, something verging on cruelty, something that resists reason, but nor is it instinct: something that remains there with the same blind stubbornness with which blood persists in its course and the earth in its immovable orbit and all beings in their obstinate condition of being, something that eludes words the way the water in the stream eludes stone, because words are only made for saying to each other, for saying the sayable, when the sayable is everything except what rules us or makes us live or matters or what we are or what that nun is and that journalist who is me dancing beside Miralles’ grave as if their lives depended on that absurd dance or like someone asking for help for themselves and their family in this time of darkness.