Frank Sinatra’s peak years as a performer occurred well before I was born. I’d heard of him and seen him on TV while growing up, of course, but nothing stuck, and I didn’t seek out his recordings. Far from it: Frank Sinatra?! He was even older than my own parents! Not that anyone, let alone a child, who hasn’t experienced some of life’s peaks and valleys could relate to the emotional shadings that Sinatra always brought to his song interpretations.

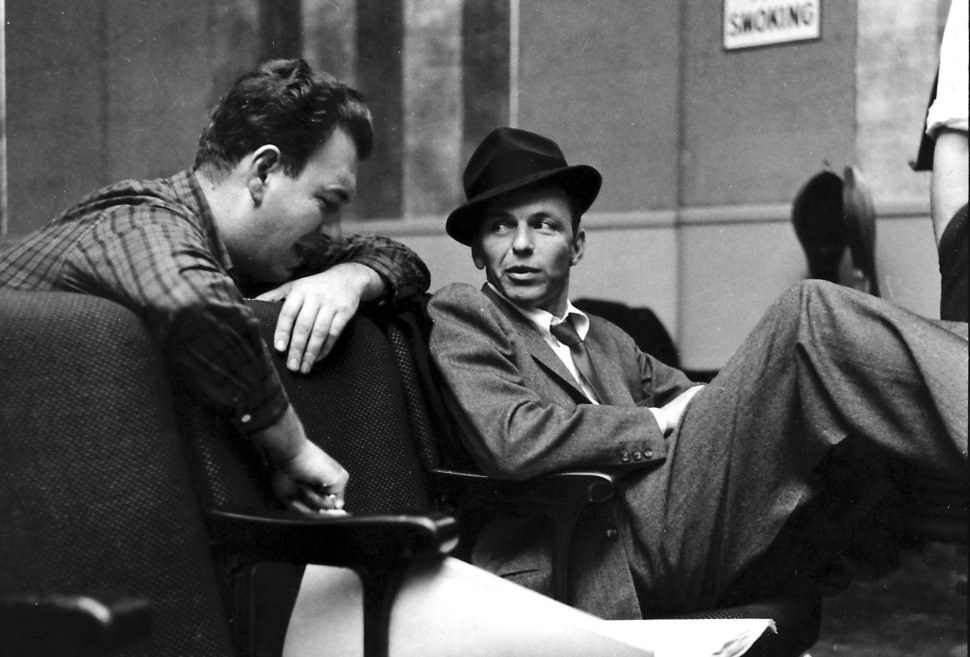

I was well into my 20’s by the time Sinatra generated blips of real consequence on my radar screen. At some point in the early 90’s, the 3-CD set, The Capitol Years, beckoned to me from the shelves of a friend’s music collection. This compilation of 75 songs was released in 1990 to honor Sinatra’s 75th birthday. His years at Capitol Records, from 1953-1961, were among the most successful and productive of his career. Of the sixteen LPs he released on the Capitol label, nine were the product of an extraordinarily fruitful collaboration with conductor/arranger Nelson Riddle.

Two boys from Jersey, Nelson Riddle (Oradell) and Frank Sinatra (Hoboken). Sinatra, always stingy with praise, referred to Riddle as “the greatest arranger in the world.” Of Sinatra, the arranger said, “It’s not only that his intuitions as to tempi, phrasing, and even configuration are amazingly right, but his taste is so impeccable…there is still no one who can approach him.”

Two boys from Jersey, Nelson Riddle (Oradell) and Frank Sinatra (Hoboken). Sinatra, always stingy with praise, referred to Riddle as “the greatest arranger in the world.” Of Sinatra, the arranger said, “It’s not only that his intuitions as to tempi, phrasing, and even configuration are amazingly right, but his taste is so impeccable…there is still no one who can approach him.”

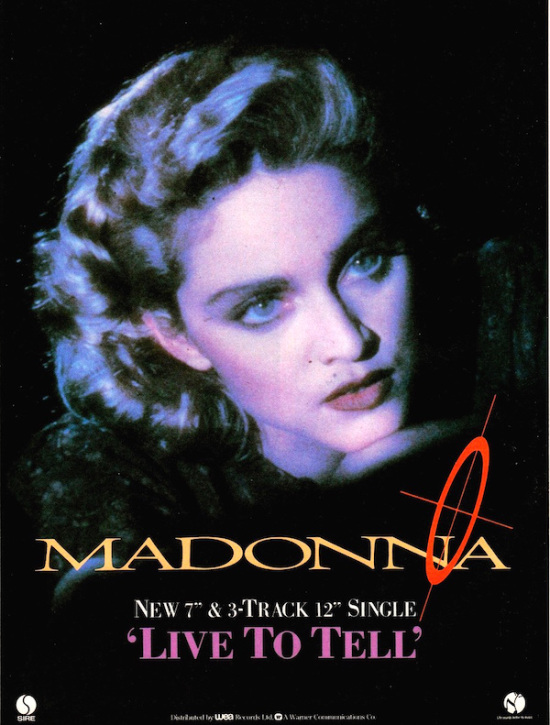

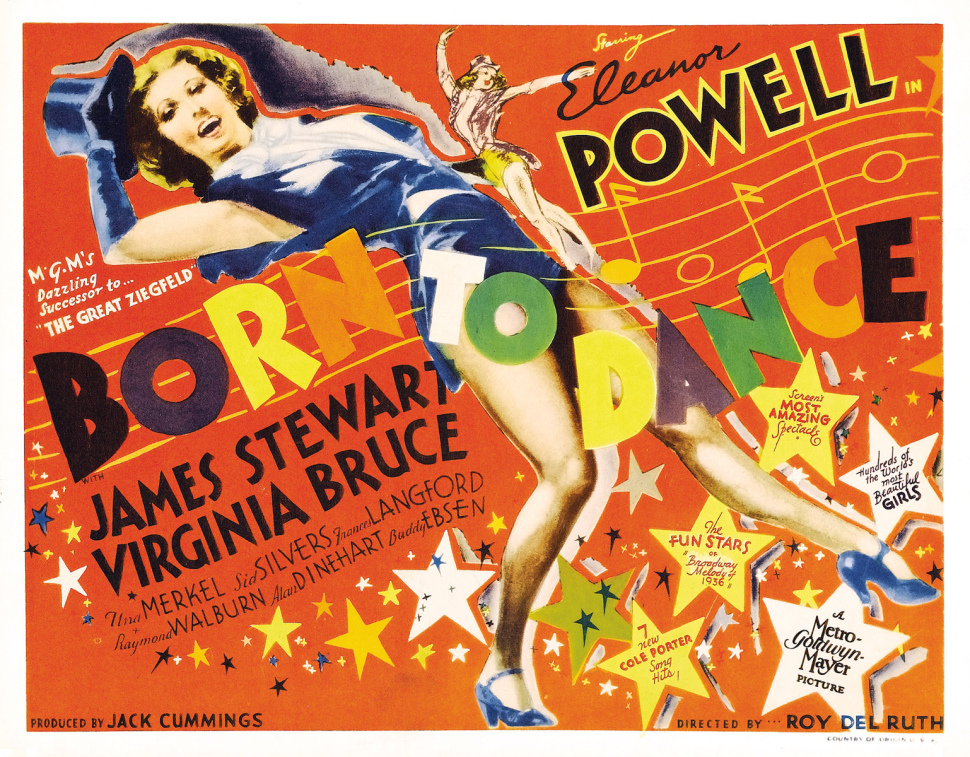

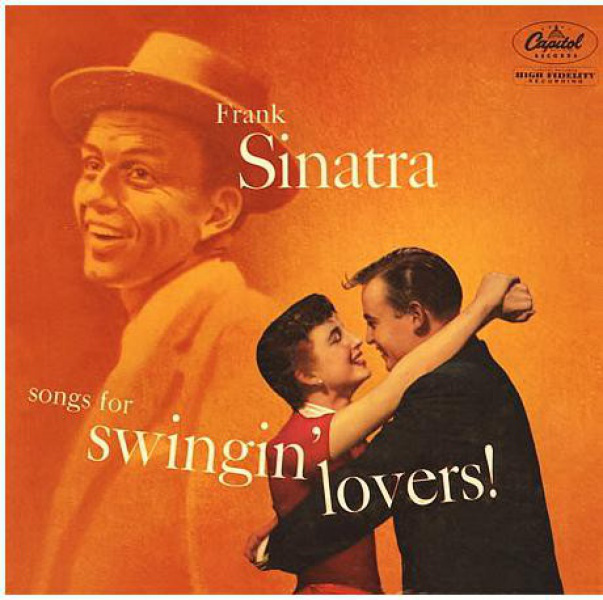

My discovery of The Capitol Years compilation–not only the music but the extensive liner notes (geek!)–propelled me in short order to the individual albums. My favorite, originally released in 1956, is Songs For Swingin’ Lovers!, and my favorite song on it is the Cole Porter classic, “I’ve Got You Under My Skin.” Porter wrote the song in 1936 and it was featured in an MGM musical, Born To Dance, released that same year.

Above left: Cole Porter, native son of Peru, Indiana. Above right: Jimmy Stewart with Virginia Bruce, who sang the song in the film (see below).

Above left: Cole Porter, native son of Peru, Indiana. Above right: Jimmy Stewart with Virginia Bruce, who sang the song in the film (see below).

In addition to Stewart and Bruce, the cast included The Tin Man, Buddy Ebsen.

In addition to Stewart and Bruce, the cast included The Tin Man, Buddy Ebsen.

I knew the song because I’d played it from the fake books and Great American Songbook collections that were always on the piano when I was a kid. But my juvenile keyboard noodling never could have prepared me for the work of Sinatra, Riddle, and a studio full of musicians–eight brass, five saxophones, four rhythm/percussion, and 16 strings. The song, which was an 11th hour addition to the group of numbers that would appear on the album, was recorded in January 1956 at KHJ Studios in Los Angeles. Riddle pulled the arrangement together quickly–mindful of Sinatra’s instruction, “I want a long crescendo” leading up to the bridge–and is said to have finished it off in the car as his wife drove him to the studio.

According to Riddle, Sinatra “wanted an instrumental interlude that would be exciting and carry the orchestra up and then come on down where he would finish out the arrangement vocally.” Riddle’s influences in attempting to fulfill Sinatra’s request included Ravel’s Boléro–“Now that’s sex in a piece of music,” said Riddle–and a 1952 Stan Kenton number, “23 Degrees North, 82 Degrees West”, whose opening bars featured Afro-Cuban-inflected rhythmic lines played on trombone. [The latter number takes its title from the co-ordinates for Havana]. Riddle charted out a slow, tension-building crescendo for bass trombone and strings, to be followed by an explosion of brass, featuring an 8-measure solo to be improvised by trombonist Milt Bernhart.

What we hear on the album didn’t come easily that night in the studio: it was the 22nd (!) take that was the charm. And it was a take, and an arrangement, that has long since assumed the mantle of legend. Sinatra’s vocals are everything you’d expect from him at that point in his career: seductive delivery, peerless phrasing. But it’s that instrumental interlude–the crescendo (starting at ~1:54 in the recording below) pushing through to Bernhart’s ecstatic solo (starting at 2:17)–that truly thrills. Listening to it, I can certainly appreciate Riddle’s appropriation of music as a metaphor for sex: seductive strings building to a brassy climax. For me, though, I can just as easily appreciate it as a distillation, in musical form, of the slowly dawning realization that someone is getting under your skin (in a good way) and then, BAM!, you’re a complete goner.

https://augenblickblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/09-got-you-under-my-skin.m4a

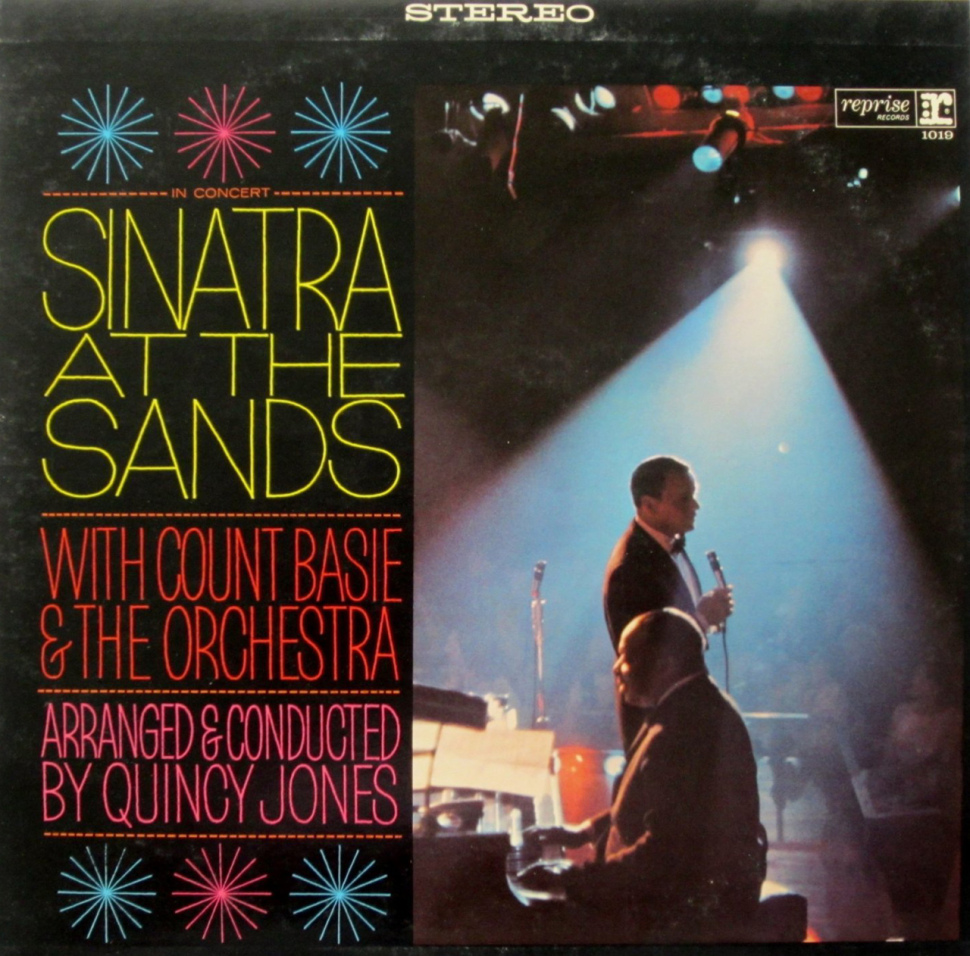

Riddle’s arrangement of “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” became a standard part of Sinatra’s concert repertoire. A live version is included on Sinatra at the Sands, recorded during a month-long run in the Copa Room at The Sands in Las Vegas in January of 1966. There, he was accompanied by Count Basie and his orchestra, conducted by Quincy Jones. You can hear, in the recording below, what Sinatra took to doing when doing the number live: shouting out, “Run for cover! Run and hide!”, as the now famous crescendo got underway. (The trombone solo here is by Al Grey).

https://augenblickblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/03-ive-got-you-under-my-skin.m4a

Sinatra at the Sands was released in July of 1966. Despite what the album cover says, Quincy Jones maintained the essential aspects of Nelson Riddle’s revered arrangement of “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” the major difference being the transfer of the string parts to the saxophones.

Sinatra at the Sands was released in July of 1966. Despite what the album cover says, Quincy Jones maintained the essential aspects of Nelson Riddle’s revered arrangement of “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” the major difference being the transfer of the string parts to the saxophones.

For anyone who still needs convincing that the Riddle/Sinatra collaboration on this song is something special, take a look at Virginia Bruce’s performance in Born To Dance. I mean, it’s perfectly fine (yawn!), but it’s from a completely different solar system. Many artists have recorded their own versions over the years, everyone from Ella Fitzgerald to Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons to U2’s Bono (in a duet with Sinatra). Twenty years after Cole Porter wrote it, though, Riddle and Sinatra produced what for many people–myself included–remains the definitive version.

I’ve got you under my skin

I’ve got you deep in the heart of me

So deep in my heart that you’re really a part of me

I’ve got you under my skin

I’d tried so not to give in

I said to myself this affair never will go so well

But why should I try to resist when baby, I know so well

I’ve got you under my skin

I’d sacrifice anything come what might for the sake of having you near

In spite of a warning voice that comes in the night and repeats

Repeats in my ear

Don’t you know little fool

You never can win

Use your mentality, wake up to reality

But each time that I do just the thought of you

Makes me stop before I begin

‘Cause I’ve got you under my skin

I would sacrifice anything come what might

For the sake of having you near

In spite of the warning voice that comes in the night

And repeats how it yells in my ear

Don’t you know, little fool

You never can win

Why not use your mentality

Step up, wake up to reality

But each time I do just the thought of you

Makes me stop just before I begin

‘Cause I’ve got you under my skin

Yes, I’ve got you under my skin.

Milt Bernhart’s trombone solo is so highly thought of, it was referenced in pretty much every obituary written after he died, at age 77, in 2004. This is from The Guardian:

“Nowadays the idea of a trombone solo igniting a great pop record might seem quaint. But there was nothing quaint about the solo halfway through Frank Sinatra’s classic version of I’ve Got You Under My Skin, with which Milt Bernhart…created something as electrifying in its time as anything devised by Jimi Hendrix or Eric Clapton in a later generation.”

Milt Bernhart, a relatively short man, ended up standing on a box to get as close to the microphone as possible during the recording session for “I’ve Got You Under My Skin.”

Milt Bernhart, a relatively short man, ended up standing on a box to get as close to the microphone as possible during the recording session for “I’ve Got You Under My Skin.”

Three sources were immensely helpful in the preparation of this post: