Not wanted–Pinkney’s novel depicts a girl fleeing from conflict who only wants an education.

“Sec. 5. Realignment of the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program for Fiscal Year 2017. (a) The Secretary of State shall suspend the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP) for 120 days. During the 120-day period, the Secretary of State, in conjunction with the Secretary of Homeland Security and in consultation with the Director of National Intelligence, shall review the USRAP application and adjudication process to determine what additional procedures should be taken to ensure that those approved for refugee admission do not pose a threat to the security and welfare of the United States, and shall implement such additional procedures.”

“Deteriorating conditions in certain countries due to war, strife, disaster, and civil unrest increase the likelihood that terrorists will use any means possible to enter the United States. The United States must be vigilant during the visa-issuance process to ensure that those approved for admission do not intend to harm Americans and that they have no ties to terrorism.”

“The United States cannot, and should not, admit those who do not support the Constitution, or those who would place violent ideologies over American law. In addition, the United States should not admit those who engage in acts of bigotry or hatred (including “honor” killings, other forms of violence against women, or the persecution of those who practice religions different from their own) or those who would oppress Americans of any race, gender, or sexual orientation.”

–from the Executive Order on Immigration issued 27 January 2017 (full text of the order can be found here: http://www.npr.org/2017/01/31/512439121/trumps-executive-order-on-immigration-annotated).

There have been numerous lists published this week on blogs and on various social media sites about children’s literature dealing with migration and refugees. It is an issue of our times, as countries of the global south experience many of the after-effects of colonialism, racism, and global economic inequity and people leave their homeland both to escape war and violence and to seek a more economically-stable life. This past week that issue came into even sharper focus when the US president issued an executive order on immigration. The order has been referred to as a “Muslim ban” because the seven countries where visas have been halted are all predominantly Muslim countries, and the only exceptions made in the order are for “persecuted religious minorities” in these countries. There are many aspects of this that can be discussed, and I can’t discuss them all, so I just want to focus on one of the seven countries, and a children’s novel that offers red pencil correctives to some of the implications in that order.

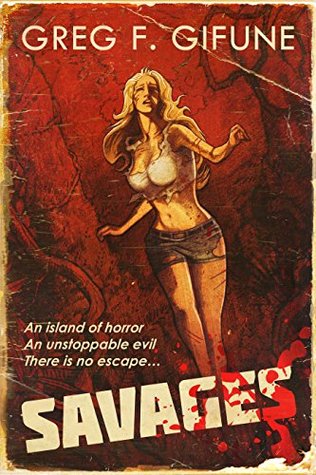

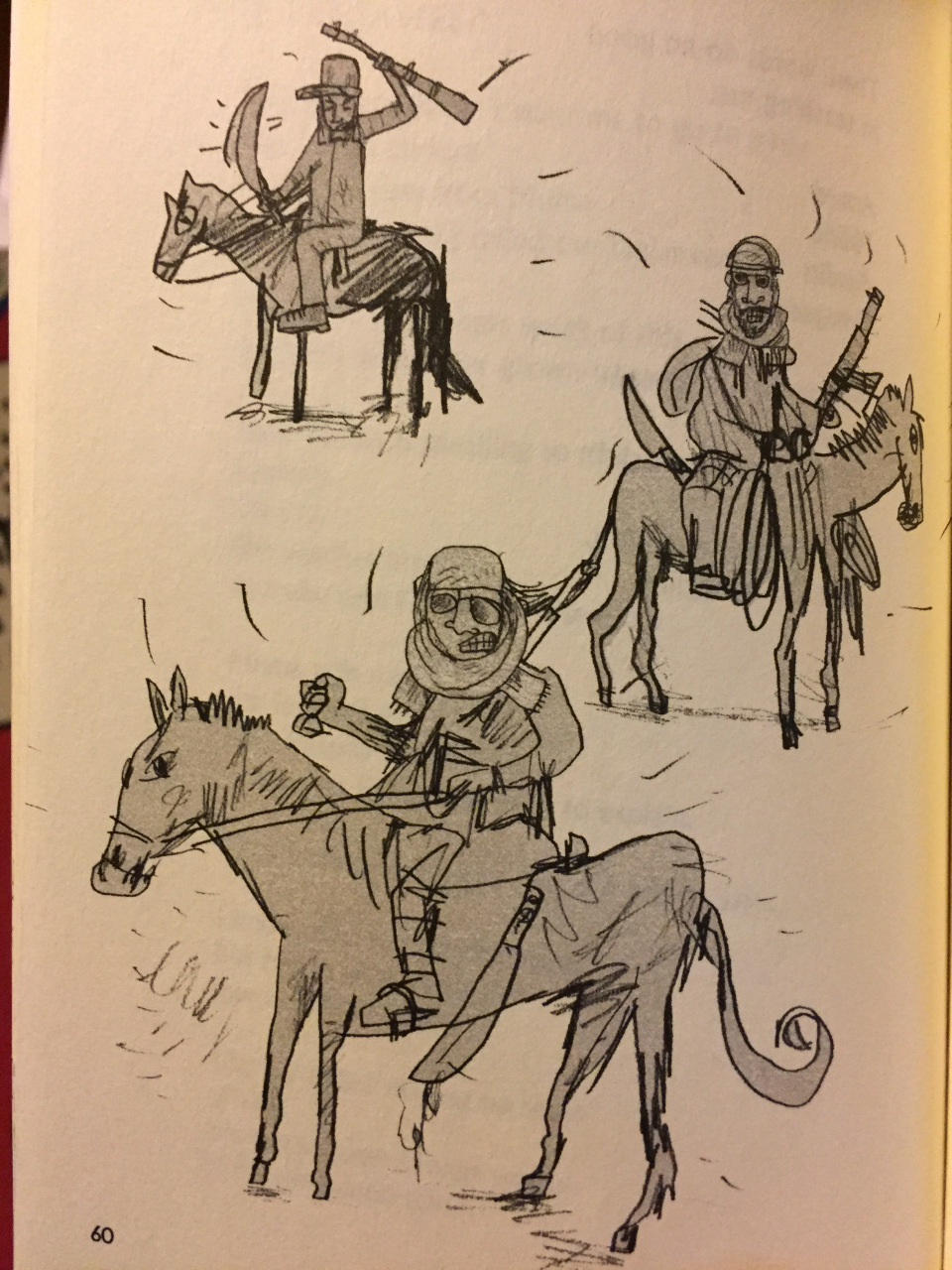

Devils on horsebacks: the Janjaweed who burn Amira’s village to the ground.

Andrea Davis Pinkney’s and Shane Evans’s The Red Pencil (Hachette, 2014) is set in one of the seven countries whose nationals can neither immigrate nor even visit the US, Sudan. Sudan is not only primarily Muslim, it has been wracked by civil war, and more than 2.5 million people have been displaced from their homes. The executive order says that, in places like Sudan, people become more desperate to get to the US, and will use “any means necessary” to do so. But Pinkney’s novel paints a very different picture. Amira, the twelve-year-old main character, is only vaguely cognizant that a place like the US exists (she sees “pink people” with “teethy mouths/ speaking English” on a “flicker box” in the camp [Red Pencil 162]). She never mentions wanting to go there, even after she arrives in the armed-guarded displaced persons camp. She longs only for her lost home, destroyed by “torches/Flames hurled to the roofs./ Our livestock pen alight with fire” (112) when the Janjaweed militia raided and burned her village to the ground. Knowing she cannot return there, however, does not mean she thinks of getting to America by any means necessary. The only other place she thinks about going is school.

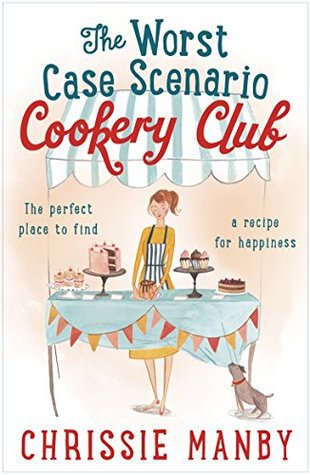

Amira uses her pencil to tell the truth about becoming a refugee.

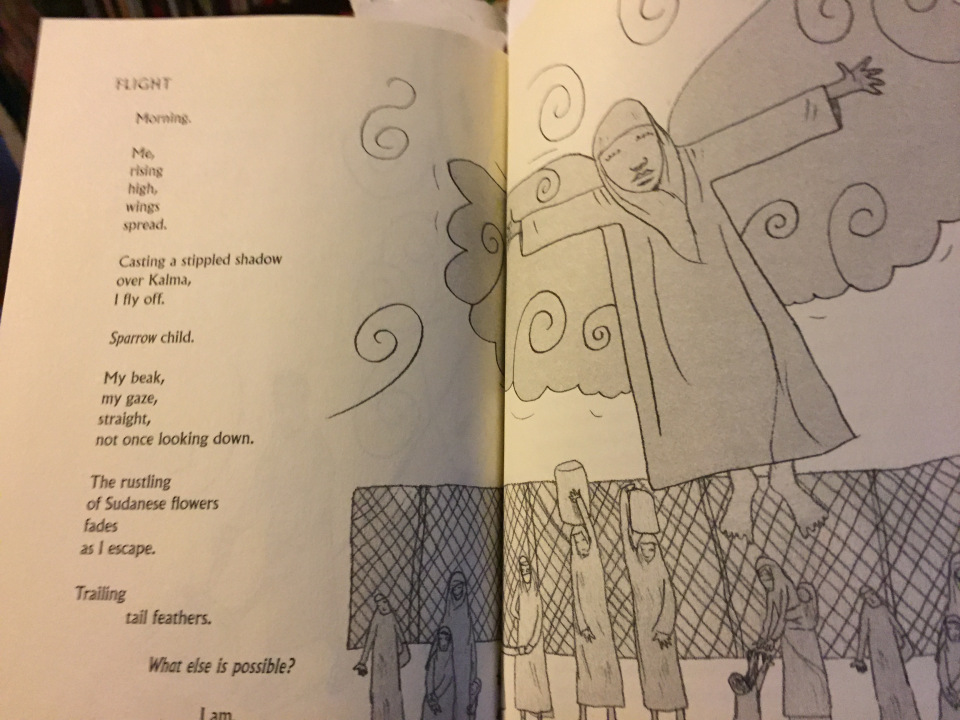

School for Amira has been a dream because girls are not encouraged to get an education in Sudan. She is not taught how to read or write until she has lost everything else and is in the refugee camp. When she is given a red pencil by a Sudan Relief worker, she does not know how to use it. She feels trapped by lined paper in the same way she feels trapped by the barbed wire fences surrounding the camp, but she learns how to ignore those lines and create something beautiful or something truthful. “the pencil’s music./ It plays on paper,/ shows me highs,/ lows,/ in-betweens” (210). Amira draws angry pictures of the “wicked helicopter . . . spitting big bullets” (208) and of the Janjaweed, “devils on horseback” (59), but she never speaks of revenge. For Amira, the Janjaweed are like the dust storms that ruin the crops, and how can you revenge yourself against nature? Amira’s only possible response is a creative one, and the red pencil she is given by an American organization allows her “soul’s bird [to] wake” (208) and, eventually, to fly.

Will refugees be able to fly free in more than their imagination? “What else is possible? I am.”

But even if her soul’s bird yearned to fly to freedom in America, she could not do so. She is not someone who might “engage in acts of bigotry or hatred (including “honor” killings, other forms of violence against women, or the persecution of those who practice religions different from their own) or those who would oppress Americans of any race, gender, or sexual orientation”. She is a child, not a potential terrorist, who has never held a weapon and only wants to learn, and create. She is the victim of war, not the perpetrator. A month ago, a real girl like Amira still would not have been allowed to come to the US as a refugee, because she is still in Sudan and to be designated as a refugee by the UN you need to be relocated to an intermediate country. Less than one percent of the world’s refugees are ever resettled, because the process of resettlement has been made extremely arduous by countries wanting to protect their borders and put their nationals first. Now, however, the executive order will prevent Sudanese from even that much hope, until and unless someone else’s red pencil strikes through the refugee ban. Fiction such as Pinkney and Evans’s The Red Pencil allows us to humanize an experience not one of us would choose.

Advertisements Share this: