Originally published by the Quietus.

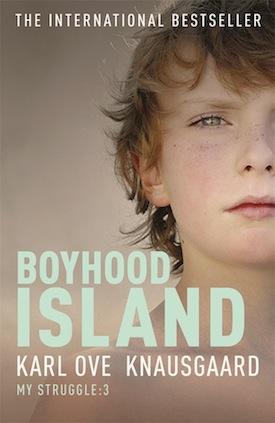

In many ways the third volume of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s fiercely-debated memoir is the smallest – in both its scope and in its physical size – and the most banal thus far. For a sequence of works which appear to be singlehandedly redefining the quality and value attached to banality in literature this no small feat. This section of the monumental work, published in the UK asBoyhood Island, focuses on Knausgaard’s life as a small child: his first experiences at school, his trips to the remote farm where his grandparents live and his first time being in love. In the shadow of these experiences lies the relationship with his father which, here, we find at its most visceral.

Knausgaard’s vulnerability by virtue of his youth – coupled with the fact of his family’s dependence on his father – ensures that he exists in a state of permanent anxiety: the subterranean drone of the unthinkable has weakened in Boyhood Island, the disturbing aural notes of the text which left the previous volumes perched on the abyss have been replaced by a more direct current – one of immediate danger, which equally permeates and infects every level of the text. Every motion of his body and movement of his tongue, each word and action, carries with it a component of fear, a sense of danger at how his father might react. This danger is a reflection of another – the inherent danger of the practice of autobiography itself.

Knausgaard’s work exemplifies that relation drawn by Michel leiris between the writing of autobiography and the act of the bullfighter. Each has a code which they must follow: the matador, the theatrical code, centuries old, of luring the bull in, of putting their body in danger before the final strike can be administered, and the writer the code of authenticity – the strict adherence to the facts of their own life. The level of adherence to their respective code is proportional to the amount of peril they submit themselves to: in the writer’s case this risk is the overturning of relationships with family and those close to them, the airing of undesirable facts of their character which threaten to affect the manner in which their work is read in future and the revealing of their style as an author when they are at their most threatened. The images cannot be doctored or softened by imagination, quite the opposite, this is ‘the negation of a novel’.

In his fiercely-direct and extended prose, Knausgaard exemplifies this relation to risk par excellance. His code of authenticity is of the highest order such that he has risked not only his life, so to speak, but also his potential material – his very status as a writer. So complete is the fragmentary project he has completed that it threatens to annihilate his ability to forge fiction from those experiences he has as they have been offered/sacrificed (Ofret, the German word which denotes both these terms seems appropriate) for truth. Like Bazin’s remarks in his review of The Bullfight (Braunberger, 1951), the montage of images used by Knausgaard is not employed as it was by filmmakers such as Eisenstein and Kulechov, whereby meaning was imparted between the two contrasting frames and to suggest symbolic abstract relations, but rather, as it is in Braunberger’s film, to create physical realism. The seamlessness of this technique is such that the linking of two instances of fact perfectly substitutes for the image of a non-existent event that the reader imagines they have experienced despite its absence. The directness of the method of exposition erodes the gaps between the fictional and the factual so that they can no longer be seen. This is what gives the text its malleability and the ‘ballet of death’ can therefore be openly revealed. This is what gives the risk aesthetic value: it, like the matador’s sculpted figure as he ritually moves in front of the charging bull, reveals the presence of a true death and life underneath the text, unclouded by any unnecessary embellishment.

This death, which hangs over both The Bullfight and My Struggle is what gives the banal its qualities of unthinkable horror. In interview Knausgaard has previously alluded to a connection, on a thematic level, between writing the series and the horrific acts committed by Anders Breivik on 22 July 2011: the turning away from life, the translation between the unthinkable act and the literary act. In Breivik’s case the transcendence was from literature to unthinkable violence, in Knausgaard’s it was from the unthinkable act of life to literature. The fact that the individual instants of life very closely resemble one another is something which is hidden from human thought by the duration of consciousness. Due to the fact that no single moment of one’s own life can ever be repeated, even though it may be an almost identical copy of another moment, the unspeakably horrific repetitiousness of all life is accepted by one’s own mind as simply the continuation of conscious experience. Human consciousness concedes its recognition of this continual sameness, nullifying it as the innocuous ‘passing of time’ so that it may avoid facing the unthinkable. The only moment which radically abandons this concession of consciousness is death, which is the single moment when conscious duration can no longer be maintained. No wonder that Heideggerian attunement is allied so closely with anxiety, boredom and wonder: the horror of what actually is reveals itself at those moments when thought fails.

What makes My Struggle so astounding is its ability to show this concession of consciousness for what it is: exactly that – a concession. Knausgaard offers his own life up in order to make this truth apparent; his act of writing creates the lens of repetition which allows the reader to see the ordinariness of these seemingly-simple moments of objective time and glimpse the undercurrent of death present in the emptiness of every one of them. It reaches beyond the Modernist narratives which show the collapsing form of the novel – beyond the reaches of Bolano’s 2666 – crystallising an image which allows the reader to experience the repetition of that which can happen only once, simultaneously negating not just the form of the novel but also the ability of the writer to continue to be. The result is a work of such sincerity that, to paraphrase Baudelaire, the paper shrivels and flares at the touch of his fiery pen.

Advertisements Share this: