Okay, I lied. These are great tips, but not necessarily the top four, but numbered lists are pretty irresistible. For some reason we love them—Top Six Beauty Tips, the Ten Best Eats in Portland, Eight New Looks for You, 13 Reasons Why.

Maybe we like the promise of something simple, definitive, brief—condensed wisdom. The other day I started browsing through a compilation of writing advice put together by the amazing Maria Popova, who writes the blog Brain Pickings. It’s a guide to 117 columns she’s written over the years on authors and their advice to other writers.

It’s well worth checking out all 117 essays for inspiration and entertainment, but I focused on the ones that promised to be simple lists, like Henry Miller’s 11 Commandments of Writing or Elmore Leonard’s 10 Rules of Writing.

And then I rather randomly picked four that I liked because it was fun to see them all together. It’s interesting how practical most of the tips are. Writers, it seems, do not want to talk high-faluting artsy stuff when it comes to advice to other writers. Even Henry Miller’s list was surprising mundane, mostly counsel to himself bordering on “don’t forget to buy milk.”

I suspect as writers we know that we only hope to catch lightning in a bottle—it’s not something we have much control over. So the best we can offer is “here’s my bottle.”

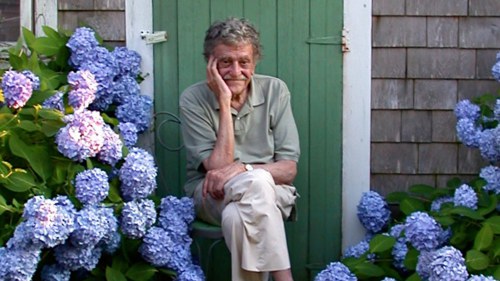

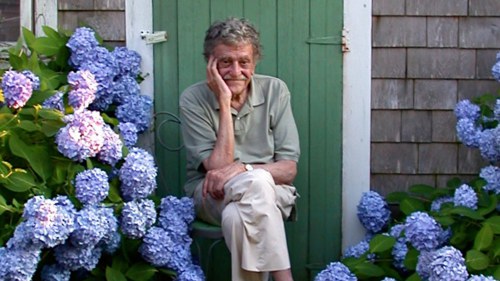

KURT VONNEGUT

Kurt Vonnegut

Use the time of a total stranger in such a way that he or she will not feel the time was wasted.

Give the reader at least one character he or she can root for.

Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water.

Every sentence must do one of two things — reveal character or advance the action.

Start as close to the end as possible.

Be a Sadist. No matter how sweet and innocent your leading characters, make awful things happen to them-in order that the reader may see what they are made of.

Write to please just one person. If you open a window and make love to the world, so to speak, your story will get pneumonia.

Give your readers as much information as possible as soon as possible. To hell with suspense. Readers should have such complete understanding of what is going on, where and why, that they could finish the story themselves, should cockroaches eat the last few pages.

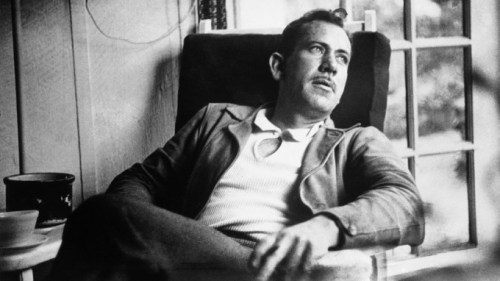

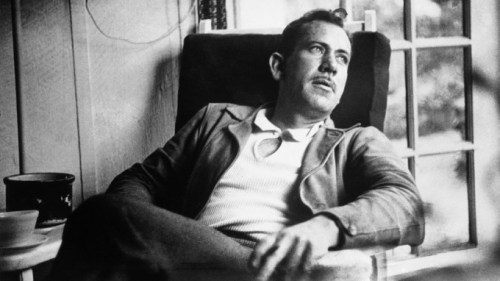

JOHN STEINBECK

John Steinbeck

Abandon the idea that you are ever going to finish. Lose track of the 400 pages and write just one page for each day, it helps. Then when it gets finished, you are always surprised.

Write freely and as rapidly as possible and throw the whole thing on paper. Never correct or rewrite until the whole thing is down. Rewrite in process is usually found to be an excuse for not going on. It also interferes with flow and rhythm which can only come from a kind of unconscious association with the material.

Forget your generalized audience. In the first place, the nameless, faceless audience will scare you to death and in the second place, unlike the theater, it doesn’t exist. In writing, your audience is one single reader. I have found that sometimes it helps to pick out one person—a real person you know, or an imagined person and write to that one.

If a scene or a section gets the better of you and you still think you want it—bypass it and go on. When you have finished the whole you can come back to it and then you may find that the reason it gave trouble is because it didn’t belong there.

Beware of a scene that becomes too dear to you, dearer than the rest. It will usually be found that it is out of drawing.

If you are using dialogue—say it aloud as you write it. Only then will it have the sound of speech.

MARGARET ATWOOD

Margaret Atwood

Take a pencil to write with on aeroplanes. Pens leak. But if the pencil breaks, you can’t sharpen it on the plane, because you can’t take knives with you. Therefore: take two pencils.

If both pencils break, you can do a rough sharpening job with a nail file of the metal or glass type.

Take something to write on. Paper is good. In a pinch, pieces of wood or your arm will do.

If you’re using a computer, always safeguard new text with a memory stick.

Do back exercises. Pain is distracting.

Hold the reader’s attention. (This is likely to work better if you can hold your own.) But you don’t know who the reader is, so it’s like shooting fish with a slingshot in the dark. What fascinates A will bore the pants off B.

You most likely need a thesaurus, a rudimentary grammar book, and a grip on reality. This latter means: there’s no free lunch. Writing is work. It’s also gambling. You don’t get a pension plan. Other people can help you a bit, but essentially you’re on your own. Nobody is making you do this: you chose it, so don’t whine.

You can never read your own book with the innocent anticipation that comes with that first delicious page of a new book, because you wrote the thing. You’ve been backstage. You’ve seen how the rabbits were smuggled into the hat. Therefore ask a reading friend or two to look at it before you give it to anyone in the publishing business. This friend should not be someone with whom you have a romantic relationship, unless you want to break up.

Don’t sit down in the middle of the woods. If you’re lost in the plot or blocked, retrace your steps to where you went wrong. Then take the other road. And/or change the person. Change the tense. Change the opening page.

Prayer might work. Or reading something else. Or a constant visualization of the holy grail that is the finished, published version of your resplendent book.

JOYCE CAROL OATES

Joyce Carol Oates

Write your heart out.

The first sentence can be written only after the last sentence has been written. FIRST DRAFTS ARE HELL. FINAL DRAFTS, PARADISE.

You are writing for your contemporaries — not for Posterity. If you are lucky, your contemporaries will become Posterity.

Keep in mind Oscar Wilde: “A little sincerity is a dangerous thing, and a great deal of it is absolutely fatal.”

When in doubt how to end a chapter, bring in a man with a gun. (This is Raymond Chandler’s advice, not mine. I would not try this.)

Unless you are experimenting with form — gnarled, snarled & obscure — be alert for possibilities of paragraphing.

Be your own editor/critic. Sympathetic but merciless!

Don’t try to anticipate an ideal reader — or any reader. He/she might exist — but is reading someone else.

Read, observe, listen intensely! — as if your life depended upon it.

Write your heart out.

I was thinking, as I wrote this, that I might comment on some of the advice—maybe something from my own experience or somesuch. But as I looked over the lists, I realized the other thing that maybe we like about lists–they don’t offer a lot of context. Instead, you, the reader, bring the context. You fill in the blanks with your own experience and decide if it rings true for you or not.

I’d love to know: did any of these tips strike you?

Advertisements

Share this:

- Tumblr

- Reddit

- Google

- LinkedIn

- Pinterest

Like this:Like Loading...

Related