by NONA BLYTH CLOUD

The Friday after Thanksgiving has been designated as Native American Heritage Day by Congress, and signed into law by President George W. Bush, but to many Americans, it is ‘Black Friday’ the unofficial start to the Holiday shopping season, a pair of events that jostle each other uneasily.

For this post in honor of Native American Heritage Month, I’ve chosen three poets who speak of the past and the present with keen visions for both.

_______________________________________________

Kimberly Blazer, a White Earth Chippewa and Anishinaabe, grew up on the White Earth Reservation in Minnesota. She is a poet, essayist, fiction writer and anthology editor. Her poetry collection Trailing You (1994) won the Native Writer’s Circle of the Americas First Book Award. In 1991, she co-founded the multicultural writers’ organization Word Warriors. Currently, she is the Poet Laureate of the state of Wisconsin.

In this poem, she uses the Japanese Haiku form within a larger poem which combines images of the natural world with phrases like “mechanical as a red oil rig” to weave the past and present together.

Haiku Journeyi. Spring

the tips of each pine

the spikes of telephone poles

hold gathering crows

may’s errant mustard

spreads wild across paved road

look both ways

roadside treble cleft

feeding gopher, paws to mouth

cheeks puffed with music

yesterday’s spring wind

ruffling the grey tips of fur

rabbit dandelion

ii. Summer

turkey vulture feeds

mechanical as a red oil rig

head rocks down up down

stiff-legged dog rises

goes grumbling after squirrel

old ears still flap

snowy egret—curves,

lines, sculpted against pond blue;

white clouds against sky

banded headed bird

this ballerina killdeer

dance on point my heart

iii. Fall

leaf wind cold through coat

wails over hills, through barren trees

empty garbage cans dance

damp September night

lone farmer, lighted tractor

drive memory’s worn path

sky black with migration

flocks settle on barren trees

leaf birds, travel songs

october moon cast

over corn, lighted fields

crinkled sheaves of white

ground painted in frost

thirsty morning sun drinks white

leaves rust golds return

winter bare branches

hold tattered cups of summer

empty nests trail twigs

lace edges of ice

manna against darkened sky

words turn with weather

now one to seven

deer or haiku syllables

weave through winter trees

Northern follows jig

body flashes with strike, dive:

broken line floats up.

Kimberly Blazer, “Haiku Journey” from Apprenticed to Justice, © 2007 by Kimberly Blaeser – Salt Publishing

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

Joseph Bruchac is an Abenaki poet, storyteller and editor who has won a Cherokee Nation Prose Award, a Hope S. Dean Award for Notable Achievement in Children’s Literature, and both Writer of the Year and Storyteller of the Year awards from the Wordcraft Circle of Native Writers and Storytellers. He was also honored with a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Native Writers’ Circle of the Americas. He edited the anthology Breaking Silence (1983), which won a American Book Award.

Steel for Rick Hill and in memory of Buster MitchellI.

Steel arches up

past the customs sheds,

the bridge to a place

named Canada,

thrust into Mohawk land.

A dull rainbow

arcing over

the new school,

designed to fan

out like the tail

of the drumming Partridge—

dark feathers of the old way’s pride

mixed in with blessed Kateri’s

pale dreams of sacred water.

II.

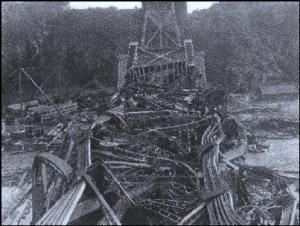

When that first span

fell in 1907

cantilevered shapes collapsed,

gave like an old man’s

arthritic back.

The tide was out,

the injured lay trapped like game in a deadfall

all through that day

until the evening.

Then, as tide came in,

the priest crawled

through the wreckage,

giving last rites

to the drowning.

III.

Loading on,

the cable lifts.

Girders swing

and sing in sun.

Tacked to the sky,

reflecting wind,

long knife-blade mirrors

they fall like jackstraws

when they hit the top

of the big boom’s run.

The cable looped,

the buzzer man

pushes a button

red as sunset.

The mosquito whine

of the motor whirrs

bare bones up to

the men who stand

an edge defined

on either side

by a long way down.

IV.

Those who hold papers

claim to have ownership

of buildings and land.

They do not see the hands

which placed each rivet.

They do not hear the feet

walking each hidden beam.

They do not hear the whisper

of strong clan names.

They do not see the faces

of men who remain

unseen as those girders

which strengthen and shape.

The Pont de Québec is a road, rail and pedestrian bridge across the lower Saint Lawrence River. The bridge failed twice during construction, at the cost of 88 lives, in 1907 and and again in 1916, taking over 30 years to complete.

“Steel” from Sing: Poetry from the Indigenous Americas – © 2011 by Joseph Bruchac

_______________________________________________

Anita Endrezze is Yaqui on her father’s side, who was born in California. She is a poet and short story writer, who has written several collections, some with poetry and short stories mixed together. She is also a painter, whose work has appeared on books covers and in shows in Great Britain. Her poetry collection at the helm of twilight (1992) was awarded the Weyerhaeuser/Bumbershoot Award.

Anonymous Is Coyote Girl From a newspaper photo and article about my godfather,James Moreno, East Los Angeles, 1950.

(Three police officers took a brutal beating in a wild free-for-all with a family, including three young girls.

From left, James, 19, and Alex, 22, in jail after the fracas

on the porch of their home at 3307 Hunter.)

Jimmy is staring off the page, hands in his pockets.

A four-button dark shirt. No bruises,

but he looks dazed.

Alex wears a leather coat and a polka-dot shirt,

which is in itself a crime.

Nowhere is there a photo of a young girl

with a face carved like a racetrack saint,

eyes with all bets called off,

grinning like a coyote.

(Officer Parks had his glasses broken

with his own sap

and was thrown through a window.)

Jimmy and Alex are my dad’s cousins,

lived on Boyle Heights and tortillas.

Mama says the cops always harassed them, those niños

from East L.A., driving their low-riders,

chrome shinier than a cop’s badge.

And why wasn’t Coyote Girl mentioned, that round-armed

girl with a punch like a bag of bees,

a girl with old eyes, her lips cracking open

as she saw the cop sailing through glass, boiling out

of Boyle Heights, skidding on the sidewalk, flat as a tortilla?

(The officers received severe cuts and bruises,

were treated at a hospital and released in time to jail the youths,

who were charged with assault with a deadly weapon.)

Two years later, I was born and Jimmy entered the church,

hands in his pockets, shoulders hunched, watching the christening.

Four drops of water, like popped-off wafer-thin buttons,

fell on my head.

No.

He never showed up that day

or any other. My spiritual guardian must’ve been there

in spirit only.

He didn’t know nada about Got and no one knows

where he is today, but I think you could find him at the end

of a knife. Or in the slash of the z

in ¡La Raza! the dark blood

reds of graffiti. Or tomatoes

grown in old coffee cans

by a white-haired man

sitting in the sun in a dark shirt,

next to an old woman growing younger every day

as I tell her story, my story,

our story

with all the grace and power

of a deadly weapon.

There are two memories of tides:

one for the deep blackness that split

away from the mother sea

and one for sea that found itself

in the daybreaks of rivers.

Yet it was all one sea

tracked by comets and the Elegant Tern,

seals in speckled pod-shaped skins,

and whales, opening their small eyes

when the hands of people drew fish

out of the salt.

Geologists tell us that the sea split

millions of years ago

before the Yoemem, Yoremem,

Kunkaak, O-Otam

curled their tongues around the names

of themselves and raised the conch shell

to their lips, so that the sound of nature

became human, too:

kalifornia vaawe

Then the sea was measured

and divided into leagues.

The Spanish ships called it dangerous

because the sea tore in two ways,

tide and rivers,

so they contained it in maps

written on dead animal skins

with ink made from dried octopus blood

Mar de la Kalifornia

Golfo de California

Then it was named the Vermilion Sea

when the red-shelled crabs clicked in the waters.

It was the Sea of Cortés

because it’s the right of the Conqueror

to claim the world in his name.

It’s his right to name hunger after himself

and to take away rivers

and children

and to give back the bare bones

of life

in the Queen’s name.

What can you say about men

who name the mountains “mother”

madre

when the worst curse they can shout

defiles their mother

in the act of creation?

Now we call the Gulf of California

polluted

with the pesticides of fields

and the wastes of factories.

And the voices of the fin-backed whale,

sardines, sea-kelp, anemone,

and turtle are quieter,

so that we have less memory

of the way it was

and less hope

for the way it will be.

In the winter I eat strawberries

from Mexico

and oranges, sectioned and split

apart

on my north continental plate.

I don’t know much about my relatives

picking the fields near Bacum, Torim.

I don’t know much about the spiny sea urchin,

except that it knows more than I

about the sea, the sea that names itself

unnameable

movable horizon.

“Anonymous is Coyote Girl” and “The Gulf of California” are both from Throwing Fire at the Sun, Water at the Moon, © 2000 by Anita Endrezze – University of Arizona Press

_______________________________________________

Joy Harjo has written, “The literature of the aboriginal people of North America defines America. It is not exotic. The concerns are particular, yet often universal.”

_______________________________________________

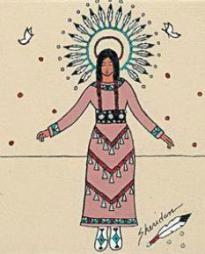

Visuals- “Her Medicine” by Sheridan MacKnight

- “Deer Woman” by Sheridan MacKnight

- The Quebec Bridge after the collapse of 1907

- Coyote

- Gulf of California

- More