By David Nilsen

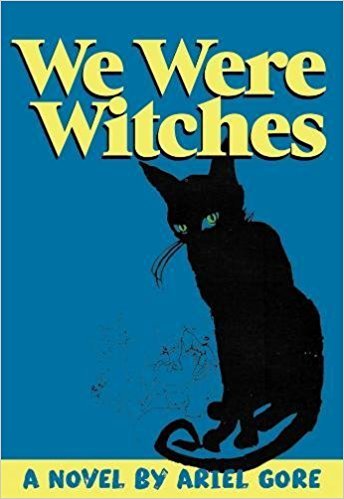

We Were Witches, underground literary goddess Ariel Gore’s newest novel, should be required reading, and I’m not even going to amend that sentence to explain for whom. This novel is a punk rock manifesto on motherhood, poverty, counter-cultural living, sexuality, identity, and writing. It’s a scalding send-up of a society that knows only how to commodify people and art, and a blazing anthem for creative folks who want to find a new path toward artistic expression.

We Were Witches is, to some extent, autobiographical, though the exact extent is never clarified. The main character is Ariel Gore herself, and her actual children, Maia and Max, feature in the book. One gathers the story is more or less true, though the exact meaning of “true” when it comes to fiction need not be parsed too finely. It is true to Gore’s mind and heart, and true for the reader.

“I am the space where I am, Gaston Bachelard wrote.

I am this closet, painted rose purple and orange.

I am this book, which is not entirely factual.”

The book charts Gore’s experiences as a single, unwed mother in the early 1990s. Her position as such brings disappointment from some of her family members and ridicule from total strangers, and she struggles with a deep, ingrained sense of shame, which is a theme throughout the book. She grew up with an abusive mother and a conflict-avoidant stepfather, and now finds herself adrift in the world and trying to find her own way. She wants to attend college, despite having dropped out of high school, and must go on welfare to make ends meet. For much of society, this automatically makes her a pariah, a freeloader. The treatment she receives from total strangers who take umbrage with her need for assistance and her “immorality” is heartbreaking and angering, and Gore is honest and skillful at displaying both the absorbed shame and the righteous defiance she feels in response.

Throughout the narrative, Gore layers in her own spiritual and political awakening as she moves through her Women’s Studies classes at college and recognizes the wrongs that have been and are being visited upon her and other women and oppressed peoples by a white, patriarchal, capitalist system. She plays with literary forms throughout the book, using class writing and reading assignments to both indict and explore the literary canon and accepted wisdom established by the same oppressive system she is laboring under. A canon composed exclusively of old white dudes isn’t gonna cut it, so Gore introduces feminist icons like Adrienne Rich, Audre Lorde, and bell hooks, quoting their writings as she reads them to her young daughter. She takes Freytag’s pyramid describing ascending action—a visual depiction of narrative structure that Gore recognized as a phallic symbol the first time her instructor drew it on the chalkboard—and turns it on its, ahem, head.

“The instructor dragged the white chalk up one side of the penis. ‘You begin with the rising action,’ she explained. She drew a quick circle around the head of the penis. ‘It culminates in climax!’”

She decides, instead, to make her story a chalice rather than a blade: “I’m gonna put a vagina in the middle of my story, not a penis,” she declares to a baffled fellow student. She infuses her novel with an unapologetically feminine perspective and energy, rooted in the personal/political inheritance that comes not only with being female, but with being a single, poor, unwed mother in conservative America.

In skewering the damaging and misogynstic subtexts of so much of our popular mythology, Gore directly addresses several popular fairy tales as the abusive, rape-y messes they are, however beloved they are held to be. She retells Sleeping Beauty and Rapunzel to expose the rot at their core. Gore takes up witchcraft, and writes about the sore deal the witches in these stories are so often given. When she reads the story of Rapunzel to her daughter, a story about a young woman who is taken advantage of by everyone in her life, she cries when the girl longs to be Rapunzel, letting down her hair for someone else to climb.

“I played along, but I couldn’t help crying, too, and I couldn’t help covering my face to pretend I wasn’t crying for all the ways I knew we would have to mold ourselves into princesses even though I knew perfectly well we were meant to be witches.”

We Were Witches, like its protagonist and her young daughter, is triumphant in spite of and even because of its tragedy. The literary world, a world ostensibly built on the inherent value of story and individual expression, told Ariel Gore—both the author of this novel and its main character—that stories had to be written a certain way, that the story of a literary career had to be lived a certain way. She decided that was as ridiculous as it was impossible. For the last two decades, she’s been carving her own path, digging her own literary structure. If that narrative structure looks more like a vagina than a penis, well, so what? Upside down, maybe Freytag’s Pyramid works better as a witch’s cauldron.

Share this: