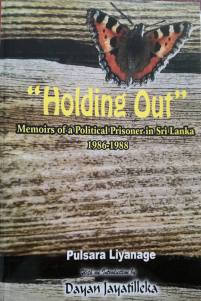

Pulsara Liyanage’s Holding Out (2017) is subtitled as the ‘Memoirs of a Political Prisoner in Sri Lanka 1986-1988’. The introduction to the book is by Dayan Jayatilleka, while Asoka Handagama has provided it a ‘Prologue’ of sorts. We are already in a curious mix of a diverse company: Jayetilleka, a proven man of many forms where the wind blows – one-time EPRLF hardcore, Premadasa-loyalist of the late-80s, Rajapakshist and a vanguard in the defense of that regime in the post-war years and so on -, and Handagama, who has always been identified with the Left Wing of politics, ideology and art, as well as as a sympathizer of the JVP of the late 1980s, appearing in the same page no doubt arouses much reader interest.

Pulsara’s subtitle – loaded as it is with much marketability – however, falls short of its promise by a long way. For, as a “memoir” of a “political prisoner in Sri Lanka” during the run up to the abominable Reign of Terror (1987-90), her narrative is a story of a privileged upper middle class, well connected girl whose incarceration, if taken as an indicator, severally undermines the extent and brutality of the violence practiced by the state and its legal and illegal milita during the years with which the narrative is concerned. Hers is a “memoir” of a “Privileged Political Prisoner”, kept in detention under the notorious Prevention of Terrorism Act at the Slave Island Police. Yet, unlike a countless thousands of common cases, hers is relatively not a humiliating or a disgraceful detention. She is housed in a relative degree of comfort, her family being knowledgeable of her whereabouts, her family being able to visit and speak to her during her detention period, and with her being able to be in contact with political figures of eminence, such as Vivienne Goonewardena and Chandrika Kumaratunga, of whom the former is said to have visited her at her cell quite regularly.

Pulsara’s subtitle – loaded as it is with much marketability – however, falls short of its promise by a long way. For, as a “memoir” of a “political prisoner in Sri Lanka” during the run up to the abominable Reign of Terror (1987-90), her narrative is a story of a privileged upper middle class, well connected girl whose incarceration, if taken as an indicator, severally undermines the extent and brutality of the violence practiced by the state and its legal and illegal milita during the years with which the narrative is concerned. Hers is a “memoir” of a “Privileged Political Prisoner”, kept in detention under the notorious Prevention of Terrorism Act at the Slave Island Police. Yet, unlike a countless thousands of common cases, hers is relatively not a humiliating or a disgraceful detention. She is housed in a relative degree of comfort, her family being knowledgeable of her whereabouts, her family being able to visit and speak to her during her detention period, and with her being able to be in contact with political figures of eminence, such as Vivienne Goonewardena and Chandrika Kumaratunga, of whom the former is said to have visited her at her cell quite regularly.

The memoirs do little to question or to cast in a critical light the overwhelming grip of state terrorism, and its resultant structured violence of which ordinary men and women who do not have the “means” or the “ways” are more cruelly the victims. Routine harassment and violence within the Police premises are glossed over, without critical or reasonable assessment. Pulsara’s book is less about the victimization of political activists, but more about her triumph of being a privileged detainee, and how she manages to keep herself in tact through a two year period. She manages to be rational in a world that seems to crumble around her, and be of benevolent help to women like Sivamalar and Sarath: men and women in other custodian cells beside her, but who are seen helpless and hopeless than she is. She even writes a letter to Chandrika Kumaranatuna at the time of her husband Vijaya’s assassination, upholding her ideal in consoling another victimized woman at time of crisis, even while being behind bars herself.

Interestingly, for a writer who seems to be quite aware of and sensitive to the subjection of the person in custody – specially, in questionable circumstances under which many men and women have been detained under the PTA – and, then again, the treatment of the female prisoner in Police or military custody, Pulsara Liyanage’s narrative doesn’t reach beyond her singular experience. Perhaps, she was lucky, or else, her background and class served as immunity, but narratives exist that document and suggest deplorable conditions in which women suspects were held; and of the harrowing experiences they have had to go through as a result of such captivity.

Interestingly, for a writer who seems to be quite aware of and sensitive to the subjection of the person in custody – specially, in questionable circumstances under which many men and women have been detained under the PTA – and, then again, the treatment of the female prisoner in Police or military custody, Pulsara Liyanage’s narrative doesn’t reach beyond her singular experience. Perhaps, she was lucky, or else, her background and class served as immunity, but narratives exist that document and suggest deplorable conditions in which women suspects were held; and of the harrowing experiences they have had to go through as a result of such captivity.

For me, the most compelling narrative comes from Rohitha Munasinghe, who relates to sexual slavery to which women in military captivity were subjected to, as witnessed by him as an inmate of the infamous Eliyakandha torture camp, in Brown’s Hill (Eliyakandha), in Matara. In his Eliyakandha Wadha Kandhawura Munasinghe outlines how women are herded into a part of the encampment and are exclusively kept for the sexual urges of the soldiers. After a time, fresh batches are brought in; the used ones either being bumped off, bearing “traitor” labels, or, in rare cases, being set free. Munasinghe bases the same experience in the composition of a short story titled “Kanyaaviya” (The Virgin) in his collection Raaga Sutra (Discourses on Passion). In this latter, a university girl is randomly abducted and taken to a torture camp and forced into sexual play, while being kept among a group of other women, detained for similar purposes. However, owing to shock and terror the girl gives no response, except to defecate under duress. After repeated attempts, she is finally taken to a bridge and shot to death, and then discarded.

In Victor Gunathilake’s 71, 89 Mathakayan (Memories of 71, 89) reference is made to a killing of two young school girls – hinted to be taken into custody by the Mahagama Police – on top of the Kalawellawa bridge. The bridge had been known to be a spot where the military would bring young men and women (some, suspects of being JVP-ers, others not) to be shot. An eerie reference is made to a pack of pariah dogs who were said to idle by the bridge, who were heftier and bigger than the rest, who feed on the remains of the shot. They are said to come running at the bridge at the sound of gun fire – Ivan Pavlov all over again. What follows is my rough translation of Gunathilake, as he relates to the witnessing of the killings of the two young girls mentioned earlier:

We could hear the ordinary sobbing of a few female voices. Just then, continuous rounds of gun fire came out, like crackers being lit. Then, all we heard was the sound of something being tipped over into the river… With the break of dawn everything became gradually clear. Two bodies were stuck among some cut bamboo which had earlier been stuck in a part of the river… The bodies were of two girls, possibly aged seventeen to nineteen. They were both clad in uniforms of some school. They weren’t in brassier or panties, and in one girl, the frock had been wrapped around her body, while she was stripped topless. The eyes were not blindfolded. As they were shot on the chest, there was a large wound in their backs… The second girl had been shot on the head and a prominent part of her face was disfigured. She wore no brassier or panties either. It was clear that they had been arrested from some other area, had been kept in the camp for a while, and had now been finally shot and dumped in the river (Gunathilake, 147-148).

The time period covered by Victor Gunathilake’s narrative is the same as the years Pulsara is concerned with; and Victor’s is a chosen excerpt from among many documented such instances, in order to develop the current discussion.

Munasinghe

Munasinghe

Pulsara’s focus is also heavily set on a number of female detainees, and as such, several key chapters deal with a range of women who are in the Police premises at varying capacities. The suspected LTTE activist Sivamalar, the girl whom Pulsara meets at the Sri Jayewardenapura Hospital who is recovering from an attempted suicide – Kanchana –, the unnamed “girl from Negombo”, the prostitutes of Slave Island etc are among the various females Pulsara factors in to the narrative. The three matrons of the Police Prison – Carolinahamy, Sallynona and Annamma – too receive a chapter of their own. But, Pulsara fails to go beyond the anecdote and establish the complexity of these different players, locating them in the overall corrupt and violent system. Partly, her superiority implied through her classed, educated and connected background makes her role play the “liberal-minded benefactor” to even these other women who have been cast to play the thoroughfare rabble to milady. The narrative of the girl from Negombo and the prostitutes – pathetically euphemized as “the twilight ladies” – are anecdotal and anecdotal alone. They, at one level, provide Pulsara the exhibition a caged animal or an alien species would, though Pulsara herself is caged: a lesser cage, if at all. The questionable way these other women are perceived and localized by the Police in the process of “meting justice”, or the legal and structural restrictions that undermine their condition as humans do not come within Pulsara the anecdote-teller’s range.

The Epilogue of the book makes several bold statements – some of them not original, but confrontational none the less. There are several references to the smashing up of suspects and of them being humiliated and reduced by the Police while being taken into custody under abusive emergency regulations. There are also accusations leveled at the JVP/DJV for attacks on moderate and alternative commentators and activists. In a selective tabulation of human rights violations, Pulsara quotes from the report later submitted by the commission appointed by President Kumaratunga to inquire into state violence during 1987-90, where Pulsara highlights the involvement of Premier Ranil Wickramasinghe in overseeing a Housing Scheme in Batalanda that was used as a torture encampment. Written in 2017, this timely re-reminder of Wickramasinghe’s alleged involvement in incarceration and murder is less obvious, but what is intriguing is her de-selection of other similar Princes of the State – among them, kingmakers and regime-changers of later times – whose hands are soaked with the blood of extra-judicial murder. The names of individuals such as Rajitha Senaratne, Gamini Lokuge, the late Ossie Abeygunasekara – some of them loyal to UNP stalwarts like Premadasa with whom Pulsara’s own friends such as Dayan Jayatilleke have broken bread with – are often heard in alternative lobbies as being directly or indirectly connected with the supervision of state-sponsored murder (one such detailed entry, for example, is found in Rajan Hoole’s The Arrogance of Power). However, for Pulsara, Ranil Wickramasinghe’s name is the one name that is politically significant to earn a mention in his memoir.

Advertisements Share this: