Though we live in a digital age, we are sometimes artificially constrained by older technologies. Like modern cars and trains that are largely designed according to the size of Roman cart paths, our reading is still shaped by a time when scrolls were the containers of words. Though we can flip through a book that falls open on our laps, we still approach reading very much like the unrolling of a scroll: as lines that emerge one after the other, from beginning to end.

Though we live in a digital age, we are sometimes artificially constrained by older technologies. Like modern cars and trains that are largely designed according to the size of Roman cart paths, our reading is still shaped by a time when scrolls were the containers of words. Though we can flip through a book that falls open on our laps, we still approach reading very much like the unrolling of a scroll: as lines that emerge one after the other, from beginning to end.

There is something to be said about the linearity of books. Stories have a beginning, a middle, and an ending. And although some great pieces play with time, the only nonlinear stories I have loved could still be plotted on a timeline, living life as humans do.

But not all stories are a single story. To read the Bible cover to cover the first time you pick it up would be a strange experience in a post-Christian culture. Anthologies, poetry collections, and the providential scraps we find in archives often lack that A to Z space-time linearity. Series like Discworld or Narnia have different kinds of internal logic and can be read in chronological order, the order of composition, or according to cycles of characters and tales found within the series. Not all stories are a single story.

The Silmarillion is one of these books that is not a single story. The Silmarillion we have is not all the Silmarillion that exists, and in some cases–due to editorial necessity–has more than the original Silmarillion drafts had. It is an edited text, drawn from a living collection of texts, artificially sealed in time and compiled so that lovers of Middle Earth can find their way to the Legendarium behind The Lord of the Rings. It is not one text, but many texts, the many stories of many peoples from many lands and languages.

The Silmarillion is one of these books that is not a single story. The Silmarillion we have is not all the Silmarillion that exists, and in some cases–due to editorial necessity–has more than the original Silmarillion drafts had. It is an edited text, drawn from a living collection of texts, artificially sealed in time and compiled so that lovers of Middle Earth can find their way to the Legendarium behind The Lord of the Rings. It is not one text, but many texts, the many stories of many peoples from many lands and languages.

The Silmarillion is broadly chronological in the way that the Bible and Narnia are chronological, moving from genesis to the fall of sentient creatures, through the heartache and great deeds of its heroes to the dawn of a new age. But, like these, The Silmarillion has a number of genres within it and spans great ages. And, like the Bible at least, The Silmarillion is better reread than read, offering great challenges to the uninitiated and great obstacles to emerging readers who are not familiar with this kind of literature.

Perhaps one of the unnecessary challenges to reading The Silmarillion is the linear nature of the task. What if we thought about technology and reading in a new way to create a new kind of reading experience of Tolkien’s great work?

If I can summarize the challenges of reading The Silmarillion, they are these:

If I can summarize the challenges of reading The Silmarillion, they are these:

- an archaic style, especially in the mythic and dialogue portions

- complex geographies that cover multiple ages and includes lands that cannot be mapped

- an intense interest in languages, which are not always translated and can be difficult to pronounce (and thus hard to remember)

- a large number of critical characters, many of whom have multiple names

- names that have an internal linguistic and cultural logic but are also chosen because they are beautiful (euphonic, or phonaesthetic), with the result that the names of kin often sound similar and blur in the mind

- myths, epics, sagas, and tales strewn across a grand timeline that is not always evident in the text itself

The only way to conquer the first point is by spending time reading Tolkien and authors that influenced him–Arthurian tales, Nordic sagas and medieval poetry, and authors like William Morris. The other points, however, have been anticipated (except one) by Christopher Tolkien as he edited The Silmarillion. My text has an index of names, basic family trees, some maps, a pronunciation guide, and some elements in Elven languages that occur again and again. The only thing it is missing is a timeline, which you can find easily enough online. The editor, though, is attuned to the challenges that come for virgin readers.

However, even with this dandy text, this is not a perfect way to read. I only own one copy of The Silmarillion, so flipping back and forth between the text and the appendices is challenging. And, honestly, the maps on a paperback page are not very good at all. I can open up my Sibley-Howe map of Middle Earth, but it only covers a part of the whole Legendarium. Far better are the online resources, where the LOTR Project and other websites have gathered maps, chronologies, genealogies, languages, and text linkages together for the reader.

However, even with this dandy text, this is not a perfect way to read. I only own one copy of The Silmarillion, so flipping back and forth between the text and the appendices is challenging. And, honestly, the maps on a paperback page are not very good at all. I can open up my Sibley-Howe map of Middle Earth, but it only covers a part of the whole Legendarium. Far better are the online resources, where the LOTR Project and other websites have gathered maps, chronologies, genealogies, languages, and text linkages together for the reader.

This means, however, that if I am going to truly read The Silmarillion and try to make all the links possible, I have to supplement the paper book either with a big paper map open and my phone app, or at my computer desk with multiple screens. Honestly, that’s a difficult way to read with a paper copy open.

Yet, the technology exists for a heightened reading of The Silmarillion, and history provides with a great model of how to do that.

Let’s begin in history.

The ancient Jews are a remarkable people. An oppressed confederacy of small tribes, as exiles under the brutal dominion of some of the greatest empires of history, they managed to collect together one of the most remarkable collections ever known. With the possible exception of Luke and Acts, the entire Bible is written by Jews, and that book is just a part of their religious literary legacy.

The ancient Jews are a remarkable people. An oppressed confederacy of small tribes, as exiles under the brutal dominion of some of the greatest empires of history, they managed to collect together one of the most remarkable collections ever known. With the possible exception of Luke and Acts, the entire Bible is written by Jews, and that book is just a part of their religious literary legacy.

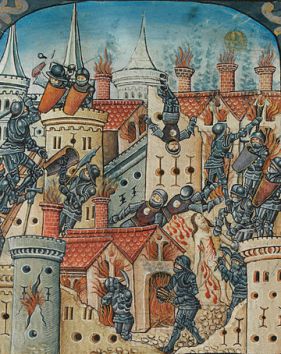

While the story is more complex than I am making it sound, a critical moment in Jewish history was when the Roman hammer fell on Jerusalem. Various Jewish political forces united to throw off the Roman yoke in 66 CE. By 70 CE, Jerusalem was sacked, the Temple was razed to the ground, and 10% of Judea’s people were lost (as seen in the Arch of Titus above). Though a second rebellion was attempted in 132-5 CE, even after the first Jewish war, the people knew that Jews would never have the same relationship with Rome again.

While the story is more complex than I am making it sound, a critical moment in Jewish history was when the Roman hammer fell on Jerusalem. Various Jewish political forces united to throw off the Roman yoke in 66 CE. By 70 CE, Jerusalem was sacked, the Temple was razed to the ground, and 10% of Judea’s people were lost (as seen in the Arch of Titus above). Though a second rebellion was attempted in 132-5 CE, even after the first Jewish war, the people knew that Jews would never have the same relationship with Rome again.

We do not know the whole story, but we do know that something happened in the first few years after that war that sealed in the Jewish understanding of Scriptures. Called by historians the Council of Jamnia, a number of rabbis are believed to have retreated from Jerusalem to set the text of the Hebrew Bible–the same text that makes up the Christian Old Testament. In the cultural pressures and persecutions of the next century, Jewish leaders had to deal with two realities. First, how can they be the people of God without the temple? Second, how do they relate to the followers of Jesus that were now part of every synagogue? While the second question worked itself out in various ways–the persecution of the Romans on both Jews and Christians served to separate the two groups–scribes and rabbis began to shape the Jews into a people of the book.

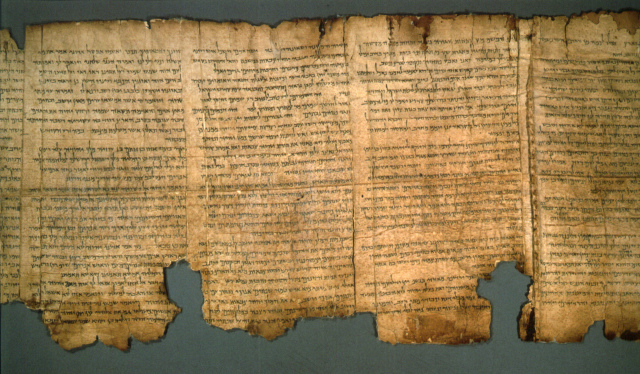

This meant thinking about books differently. I have seen the 2200-year-old Qumran scroll of Isaiah, 24 feet of precise Hebrew text on 17 sheets of parchment. And this is just one of many scrolls that made up the Hebrew Bible. The Torah would have been a series of five scrolls and the minor prophets on another single scroll. Though it would be unusual for a synagogue to have a complete collection of texts–a set of Torah might have had the relative cost the equivalent of a suburban bungalow today–the scrolls they had lived like rare wine bottles, taken down carefully from their precious space and experienced as a single unit of deep goodness.

This meant thinking about books differently. I have seen the 2200-year-old Qumran scroll of Isaiah, 24 feet of precise Hebrew text on 17 sheets of parchment. And this is just one of many scrolls that made up the Hebrew Bible. The Torah would have been a series of five scrolls and the minor prophets on another single scroll. Though it would be unusual for a synagogue to have a complete collection of texts–a set of Torah might have had the relative cost the equivalent of a suburban bungalow today–the scrolls they had lived like rare wine bottles, taken down carefully from their precious space and experienced as a single unit of deep goodness.

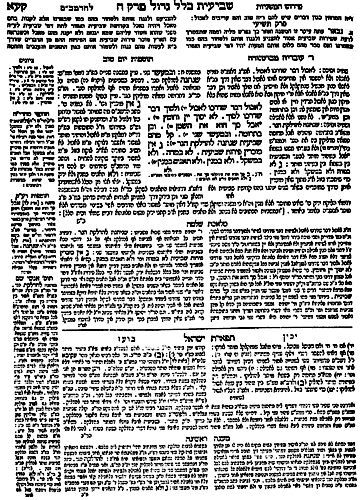

What the 2nd- and 3rd-century scribes and rabbis did, however, was to think about what it would mean to live the “way” as Jews scattered across the earth, alienated from land and temple. One of the things they did was create the Mishnah, a word that means “studying by repetition.” Jewish scribes wrote down the “Oral Torah,” the traditions about how to read and live Scripture. The scribes clustered these customs and teachings around bits of Scripture on the page, adding commentary. What you see on the left is a clearly non-linear text: multilingual, multi-generational, circular, layered, and attuned to the different levels of reading necessary to applying text to real life.

What the 2nd- and 3rd-century scribes and rabbis did, however, was to think about what it would mean to live the “way” as Jews scattered across the earth, alienated from land and temple. One of the things they did was create the Mishnah, a word that means “studying by repetition.” Jewish scribes wrote down the “Oral Torah,” the traditions about how to read and live Scripture. The scribes clustered these customs and teachings around bits of Scripture on the page, adding commentary. What you see on the left is a clearly non-linear text: multilingual, multi-generational, circular, layered, and attuned to the different levels of reading necessary to applying text to real life.

As time went on, the Mishnah (c. 200 CE) was taken up into the Talmud, a word that means “learning.” The Talmud–the first page of a copy of the Talmud is on the left–set the Mishnah at the centre of its text, then filled it out with the debates of faithful scholars. If a scholarly reading of either the law or the oral law was reasonable, it was included. There is an old saying that if you give a text to two rabbis you will get three opinions. This is the spirit of Talmud, where the critical thinking necessary to a life of faith–often a life lived under intense social pressure–requires a diversity of intelligent voices. The Talmud sought to bring together all the resources for reading a biblical text onto a single page, including background knowledge, conversations about language and meaning, and how to apply the text in real life.

As time went on, the Mishnah (c. 200 CE) was taken up into the Talmud, a word that means “learning.” The Talmud–the first page of a copy of the Talmud is on the left–set the Mishnah at the centre of its text, then filled it out with the debates of faithful scholars. If a scholarly reading of either the law or the oral law was reasonable, it was included. There is an old saying that if you give a text to two rabbis you will get three opinions. This is the spirit of Talmud, where the critical thinking necessary to a life of faith–often a life lived under intense social pressure–requires a diversity of intelligent voices. The Talmud sought to bring together all the resources for reading a biblical text onto a single page, including background knowledge, conversations about language and meaning, and how to apply the text in real life.

I think the Talmud is a model for new reading experience of The Silmarillion in two key ways.

First, it would not be difficult to create a text that looks like the Talmud. Imagine the text of The Silmarillion framed by brief biographies of characters (including alternate names), geographical notes, pronunciation hints, known words written in Elven tongues, family trees and intimate connections, and echoes of other stories in the Legendarium. The Silmarillion Talmud could also have relevant variants and Tolkien’s own comments about the text from letters and marginalia.

First, it would not be difficult to create a text that looks like the Talmud. Imagine the text of The Silmarillion framed by brief biographies of characters (including alternate names), geographical notes, pronunciation hints, known words written in Elven tongues, family trees and intimate connections, and echoes of other stories in the Legendarium. The Silmarillion Talmud could also have relevant variants and Tolkien’s own comments about the text from letters and marginalia.

The paper copy of the Silmarillion Talmud could be laid out like an Archaeology Study Bible, with text on top and footnotes on the bottom, and sprinkled throughout with text cross-references, beautiful maps, and quick studies. Or the circular nature of the Mishnah and Talmud could be kept. Either way, this would be a big, thick book with large colour maps and all the references you need on a single page so a quick glance to the margin will make a necessary link in reading.

Plus–and this might be controversial–the Silmarillion Talmud could include the opinions of scholars when they have critical disagreement about a passage. Is it not true, after all, that if you put two Tolkienists in a chatroom together they will emerge with three opinions (and sometimes a digital bloody nose)? What better way to capture the constructive diversity of the field than a Silmarillion Talmud?

Second, with the Talmudic principle of non-linearity and diversity in mind, imagine what the digital possibilities would be! Though a phone screen might be too small, if we want to read with a screen open, The Silmarillion is the perfect text to test the capability of tech-forward reading possibilities for our generation.

Second, with the Talmudic principle of non-linearity and diversity in mind, imagine what the digital possibilities would be! Though a phone screen might be too small, if we want to read with a screen open, The Silmarillion is the perfect text to test the capability of tech-forward reading possibilities for our generation.

Begin with one of my favourites, the LOTR Project (though true Tolkienists would know what the full digital landscape has to offer). This website has interactive maps linked in with the critical timeline. There is a lot of potential for hours in front of your screen at the LOTR Project when you add in the blogs, infographics, statistics, and cool apps. I mean, just check out the Periodic Table of Middle Earth or the Six Degrees of Sauron utilities. Awesome.

Beyond the LOTR Project there are commentaries, podcasts, blogs, encyclopedias, lexicons, films, and audiobooks. Imagine having the text open on your screen and you come to a name you do not know. You shadow the mouse above the name and it gives you a brief bio or geographical location. You can click on the name and get pronunciation, etymology, history, importance to the story, place history or kin connections, and a map that shows you where you are in space and time. There are a few Peter Jackson film clips that are relevant that might highlight a scene, or you may want to read along with Marin Shaw or Achim Höppner’s rich voices. Or you may want to pause your reading and spend some time in that section with the Tolkien Prof (Corey Olsen).

All of this by the click of a mouse or the tap of your finger on an iPad.

I am not naive enough to think that the legal aspect of this is even remotely possible, or that the price point is reasonable (though I think the Digital Silmarillion Talmud would not be that costly as much of the material is already produced). I just think that in opening up The Silmarillion and trying to read it beginning to end is an unnecessarily rigorous project when you consider the models we have from history and the tools we have through digital technology (as well as the time of Tolkien nerds lovingly devoted to the craft).

I am not naive enough to think that the legal aspect of this is even remotely possible, or that the price point is reasonable (though I think the Digital Silmarillion Talmud would not be that costly as much of the material is already produced). I just think that in opening up The Silmarillion and trying to read it beginning to end is an unnecessarily rigorous project when you consider the models we have from history and the tools we have through digital technology (as well as the time of Tolkien nerds lovingly devoted to the craft).

More than anything, this project is true to Tolkien’s work. Creating a Silmarillion Talmud not only invites others into a deeper experience of the world he loved so much, but it would be “a treasury of good counsel and wise lore” that Elrond himself would admire. Tolkien’s work is, after all, like the Mishnah in reverse. With The Lord of the Rings at the centre, rather than moving forward as the rabbis did, Tolkien moved backwards into the already established and yet ever-living Legendarium.

So, here’s the call: Who would like to create a Silmarillion Talmud?

Advertisements If you like it, please share it: