Welcome to Alpha & Omega! The blog series where we take a look at one issue each of the two Omega the Unknown comic book series—the original from 1976-77 and the reimagining from 2007-08. In the spirit of the (now-discontinued) If It WAUGHs Like a Duck series, each post seeks to both put the issues in context of their times, but mostly in conversation with each other.

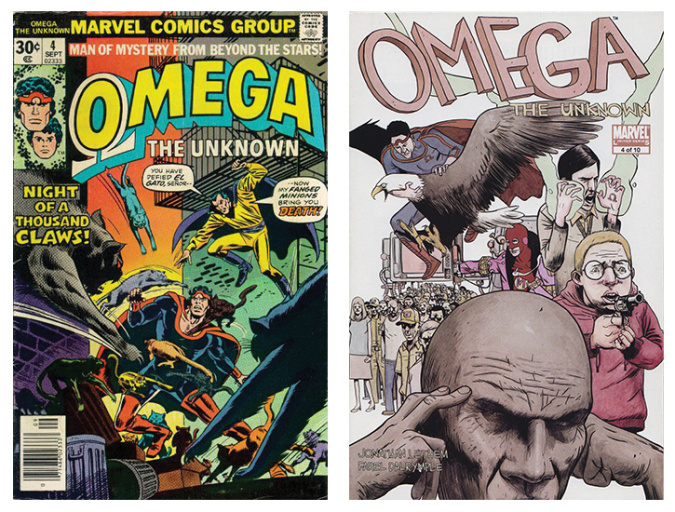

Omega the Unknown volume 1, #4

Cover Date: September 1976

Release Date: June 15, 1976

Writers: Steve Gerber and Mary Skrenes

Penciler: Jim Mooney

Inker: Pablo Marcus

Colorist: Phil Rache

Letterers: Ray Holloway and Karen Mantlo

Omega the Unknown volume 2, #4

Cover Date: February 2008

Release Date: December 5, 2007

Writers: Jonathan Lethem w/ Karl Rusnak

Penciler: Farel Dalrymple

Inker: Farel Dalrymple

Colorist: Paul Hornschemeier

Letterer: Farel Dalrymple

The Covers

Neither cover for these paired issues is particularly notable. Omega the Unknown #3 of 1976 has a cover that betrays the influence of typical superhero comics found within its pages that I write about below. Omega is surrounded by countless alley cats, with a look of fright that highlights the scenario’s absurdity, along with the absurdity of the ethnic villain, El Gato, calling them his “fanged minions.” Farel Dalrymple’s cover for volume two #4’s cover is a mess of scenes from within the book hovering over a rendition of the park statue I mentioned in the last installment, and that we learn a little more about in this one. It’s not great, either.

The Issues

And with the fourth issue, the two series begin to diverge in terms of framework and tone. They both maintain their relationship to realism, seeming to operate in some zone between typical superhero comics and reality, but while in 1976 Steve Gerber and Mary Skrenes are falling into the familiar pattern of the serialized cape book, in 2008, Lethem and Rusnak seem to be hurtling towards a climax and ending. But wait! How can that be? There are still six more issues to go in the maxi-series! My only guess is that Lethem’s tendency to challenge expectations of form and character in his fiction is raising its head to influence Omega the Unknown. He isn’t afraid to shift point of view, or to make you grow to dislike a character he wrote with charm or sympathy earlier in the book—The Fortress of Solitude is a great example of that.

The Overthinker providing an overview of the first three issues. [Click to see a larger version]

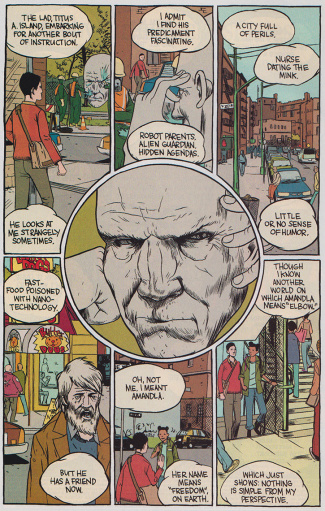

And change point of view he does. Omega the Unknown vol. 2, #4 opens with a splash depicting the strange living statue I mentioned in the last installment, getting the graffiti on him washed off. It serves as kind of a Greek Chorus, reminding us of everything going on so far. The second and third pages put the statue at the center of a distended six-panel layout (thus making seven panels, I guess), where its cloud-like thought balloons catch us up on what’s been going on with Alex and his heroic counterpart—Alex’s robot parents, his “alien guardian,” Edie dating the Mink, fast-food tainted with nano-robots, Amandla, Omega working in the food truck, creating anti-robot antibodies in the salt to protect the community, and so on. The statue, who later refers to itself as “The Overthinker,” definitely has a Uatu the Watcher type vibe, and refers to having witnessed similar events on other planets, and confirms The Mink’s seemingly facile conclusion that “Where’s there’s robots there’s blue guys,” from the previous issue. It also establishes that the Overthinker is aware of things going on way beyond the statue’s physical location in the park, because it refers to things that happened, for instance, in the secret level of the Mink’s headquarters. It seems strange to suddenly introduce this voice to the comic, but maybe Lethem or his editor felt like since so much had been going on, readers following along might need a refresher? If that is the case, it seems like a strange choice, given that I can’t imagine this is the kind of series someone would pick up in the middle, and in fact the sales records show it was quite the opposite.

This issue of Omega the Unknown vol. 2, like the previous ones, has a lot going on in it. Edie the nurse and Claire the social worker don’t really appear in it, but Dr. Devani appears at the end when he confronts Alex at the hospital where the boy was looking to check in on his schoolmate, Hugh. The doctor lets the boy know that another patient came in that night. It’s Roofie! He’s been badly beaten, but even more strangely are the Omega-shaped burn marks on his arm. How did they get there? And who is Hugh?

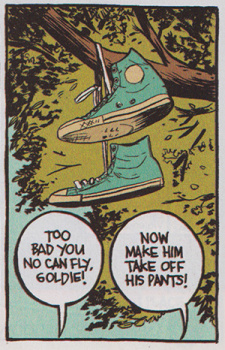

Hugh is the other nerdy white kid at Sammy Sosa Junior High School, and a frequent victim of violence and bullying at the hands of Roofie and his crew. After school one day, Alex decides to intervene when he sees trouble, but Hugh is not very appreciative of the effort. He is a broken kid, and my inference is that he knows that Alex’s attempts to help out are very likely to make the whole thing worse. He is not wrong. Roped into accompanying Roofie’s tormenting of Hugh as a bonus target, the whole group ends up in a park by the river, where the bullies throw Hugh’s shoes up into a tree, and threaten to take off his pants and throw him in the water. Before this can happen, however, drunk with his power, Roofie gets a pistol from one of his homeboys and points it at Hugh. However, to make the game even more twisted, he hands the gun to Hugh and gives him a choice, shoot the shoes out of the tree, or show he has guts and point it at him.

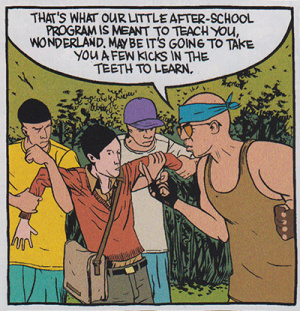

When Alex asks aloud, “What kind of place have I come to?” Roofie turns to him and responds, “That’s what our little after-school program is meant to teach you, Wonderland. Maybe it’s going to take you a few kicks in the teeth to learn.” When he turns back, Hugh is pointing the gun at him, and stammering for him to stop, so Roofie grabs Alex to use as a human shield. Realizing that this situation could not resolve in any way good, Hugh feels trapped and brings the gun under his own chin. Clutching at Roofie’s arm, Alex’s hands begin to smolder with the power of Omega and the bully is burned. He lets go, but it is too late. Hugh has shot himself. Alex runs to get help, and the bullies flee, at least one of them muttering that Roofie “screwed up, real bad.” My guess is that it was Roofie’s own homies that beat him up.

When Alex asks aloud, “What kind of place have I come to?” Roofie turns to him and responds, “That’s what our little after-school program is meant to teach you, Wonderland. Maybe it’s going to take you a few kicks in the teeth to learn.” When he turns back, Hugh is pointing the gun at him, and stammering for him to stop, so Roofie grabs Alex to use as a human shield. Realizing that this situation could not resolve in any way good, Hugh feels trapped and brings the gun under his own chin. Clutching at Roofie’s arm, Alex’s hands begin to smolder with the power of Omega and the bully is burned. He lets go, but it is too late. Hugh has shot himself. Alex runs to get help, and the bullies flee, at least one of them muttering that Roofie “screwed up, real bad.” My guess is that it was Roofie’s own homies that beat him up.

I have three thoughts about this powerful scene.

The first is that it succeeds at conveying a sense of simultaneous isolation from and a violent entanglement within social systems we’d rather avoid. The second is that this is the first time we’ve seen Alex manifest the Omega power on his palms when he was not in the presence of Omega the Unknown himself. I am not sure what this means, but it deepens the mystery of their connection. Lastly, and most complex and problematic, is how this scene recapitulates the framework of brown people equating perpetrator, while white people are the victims. While this formulation is interrogated and problematized in Lethem’s The Fortress of Solitude, not sure this series has the space and ability to do the same. Instead, it reinforces of the narratives of “bad schools” full of “hoodlums” that informs so many views of urban life, and puts white people at the center of all relations of experience.

One of the letters printed in the 1976 volume reinforces that perspective, and is a manifestation of the exact prejudice I worried about in writing about the original series’ depiction of Hell’s Kitchen. The letter by someone named “Helmsman Collins” (is he in the navy?), who gives no address, expresses satisfaction with the gritty realness of the setting. He refers to the people living in “sinkholes” like Hell’s Kitchen as “human filth.” Another letter in the issue, this one by someone named Rodney Nellis from Staten Island, also praises the realism in Omega the Unknown, and claims that Steve Gerber is “single-handedly bringing to comics a sophistication which [he]…cannot properly describe.” Of course, in his eagerness to praise Gerber, this reader has not only erased the work of any artists collaborating with Gerber, but totally erased the work of Mary Skrenes as co-writer of the series (which reminds me of the encounter she described on the letter page of issue #2, in which a fellow Marvel employee dismisses her contribution to the comic). One other letter printed in issue #4, from Tom Murphy of Newark, NJ, explains that while he (like me) had trepidations about Omega the Unknown being set in the Marvel Universe, and too quickly including guest appearances of established characters from other books, that the inclusion of the Hulk and Electro worked because the comic retained the sense of mystery about Omega and James-Michael, and did not give into the typical comic book tendency to overexplain every detail or have heroes exchange origin stories.

One of the letters printed in the 1976 volume reinforces that perspective, and is a manifestation of the exact prejudice I worried about in writing about the original series’ depiction of Hell’s Kitchen. The letter by someone named “Helmsman Collins” (is he in the navy?), who gives no address, expresses satisfaction with the gritty realness of the setting. He refers to the people living in “sinkholes” like Hell’s Kitchen as “human filth.” Another letter in the issue, this one by someone named Rodney Nellis from Staten Island, also praises the realism in Omega the Unknown, and claims that Steve Gerber is “single-handedly bringing to comics a sophistication which [he]…cannot properly describe.” Of course, in his eagerness to praise Gerber, this reader has not only erased the work of any artists collaborating with Gerber, but totally erased the work of Mary Skrenes as co-writer of the series (which reminds me of the encounter she described on the letter page of issue #2, in which a fellow Marvel employee dismisses her contribution to the comic). One other letter printed in issue #4, from Tom Murphy of Newark, NJ, explains that while he (like me) had trepidations about Omega the Unknown being set in the Marvel Universe, and too quickly including guest appearances of established characters from other books, that the inclusion of the Hulk and Electro worked because the comic retained the sense of mystery about Omega and James-Michael, and did not give into the typical comic book tendency to overexplain every detail or have heroes exchange origin stories.

Alex is the most interesting part of what is going in this issue, but it is not remotely strange. What is strange is Omega breaking the neck of a bald eagle in the park and frying it! The narration that accompanies this turn of events tries to explain Omega’s obsession with eating birds he’s killed himself (he roasts a pigeon in issue #2’s trainyard scene, and in the previous issue, Revered Upchurch brings him to the slaughterhouse for some fresh chicken), by suggesting that somehow birds resist the invasive nanotechnology making people all over Washington Heights into evil robots. Among these is Councilman Alfonzo, his infectious “Fonzie” name-plate having buried its way into his chest, so he now speaks the alien robot language with others hidden among humankind. The Mink is also infected, but luckily notices something is up when he cannot let go of a Mink action figure delivered with the nameplate. In a strange scene where we find out he keeps his father on retainer as his personal physician, we see a microscopic close up of the nanite bugs. The Mink has to get his hand amputated before the infection spreads. Little does he know that his own minions are already among the infected, as his homeless friend who showed up last issue infiltrates the organization after eating an infected burger.

Omega kills and cooks a bald eagle.

Honestly, the multiple moving parts of this series makes me feel like trying to summarize it here is an exercise in futility. I recommend just reading it for yourself.

In 1976, I worry that Omega is bending to the demands of the genre. Not only does it read very much like a typical 1970s part one of a two-issue story introducing a new, slightly ridiculous, villain, but Omega speaks!

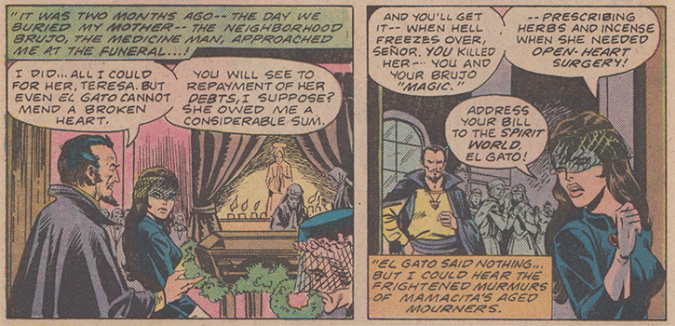

He may only speak one word, “Why?”—when confronting a woman he saves when she throws herself off the Brooklyn Bridge—but it is jarring and marked by a large balloon and small lettering meant to convey it as harsh whisper. There is no one else around to hear him speak, and the woman passes out. When she awakens, we find that Omega has brought her over to Gramps’s place above the pawn shop to recover. Gramps is happy to have “Sam” (which is what he has taken to calling the silent Omega) back, and doesn’t seem to mind helping out the distressed woman. She is Teresa Mendez, who claims to be the victim of a curse put on her by “the neighborhood brujo” called El Gato. It turns out she was unwilling to pay the outstanding debts her late mother owed to the goatee-sporting Dracula-wannabe for his ministrations during her illness. In a flashback, we see Teresa accuse him of speeding up her mother’s demise by offering her “herbs and incense” when what she need was “open-heart surgery.” El brujo’s counter claim is that she caused her mother’s death (of “heartbreak”) by seeking her “fortune in the Anglos’ world.” Now, everything around her has gone wrong—her pet fish dies, her fiancé dies, she is evicted from her apartment—and now she is convinced that for helping her, bad luck will fall upon Omega and Gramps as well.

There is certainly potential in the intra-ethnic tensions between assimilation and adherence to some traditional beliefs and customs, but I don’t think Gerber and Skrenes are the ones to explore it with any nuance, requisite knowledge, or sensitivity. Being a bilingual speaker/reader, I have long been sensitive to the inclusion of Spanish dialog in otherwise Anglophone comics, movies and TV shows. It often jangles in my ear, and resonates with clichés, stereotypical accents, and word choice meant more to signal superficial bilingual/bi-cultural inclusion to Anglos, than to actually represent Latinx people with credibility. Don’t get me wrong, I am glad the writers are doing more to include Latinx characters that are not just the thugs and winos of the neighborhood, but the lack of differentiation (i.e. what particular Latinx group are they from?), and the lazy characterization, tempers my joy at seeing any representation in an era when seeing anyone who might reflect mi gente was even less common than it is now.

There is certainly potential in the intra-ethnic tensions between assimilation and adherence to some traditional beliefs and customs, but I don’t think Gerber and Skrenes are the ones to explore it with any nuance, requisite knowledge, or sensitivity. Being a bilingual speaker/reader, I have long been sensitive to the inclusion of Spanish dialog in otherwise Anglophone comics, movies and TV shows. It often jangles in my ear, and resonates with clichés, stereotypical accents, and word choice meant more to signal superficial bilingual/bi-cultural inclusion to Anglos, than to actually represent Latinx people with credibility. Don’t get me wrong, I am glad the writers are doing more to include Latinx characters that are not just the thugs and winos of the neighborhood, but the lack of differentiation (i.e. what particular Latinx group are they from?), and the lazy characterization, tempers my joy at seeing any representation in an era when seeing anyone who might reflect mi gente was even less common than it is now.

Later, when Omega the Unknown returns from a walk (which I guess was Gerber and Skrenes convenient way of having him not be around), he finds that Teresa has been taken by El Gato. He is able to stop the car before it gets away, but he is handily defeated by El Gato, who hits hard and seems mostly unperturbed by Omega’s presumably Kryptonian blows. El brujo then calls on neighborhood cats to attack Omega, and they overwhelm him. It is only Gramps’s quick thinking that frees Omega from their assault, directing a fire hydrant spray at the felines (since cats hate water). The struggle is for naught, however. Before the battle can continue, El Gato allows Teresa to explain that she is going with him, “entirely of [her] own accord”—though Mooney draws her with a blank, apparently mesmerized, expression. The issue ends as El Gato drives off with her and Gramps admonishes “Sam” to go and set her free.

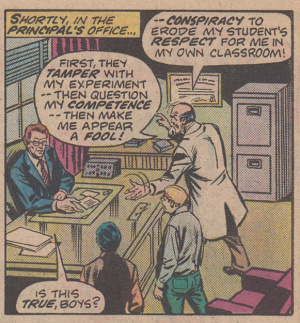

In the principal’s office

James-Michael Starling’s experiences, like Titus Alexander Island’s, are the most interesting part of the 1976 narrative in my estimation. Like Alex, JMS is still working out how to navigate school, but other students are not the only myopic bullies he has to deal with, as he has an explosive encounter with a science teacher, who takes the new boy’s warning regarding the dangerous results of a mislabeled chemistry experiment as a sign of disrespect for his authority. When John (the 1976 equivalent of Hugh) throws the smoking experiment out the classroom window to save them all, he and JMS end up dragged to the principal’s office. While the principal seems willing to listen to James-Michael and John’s explanation, the teacher remains obstinate that the students were in the wrong, and accuses them of meddling in the experiment to cause the potential danger (in truth is was the bully Nick, with encouragement of his buddies, though neither JMS, nor John rat him out). The encounter is one that is not unfamiliar to me, as coming up through school I had plenty of experiences with petty and insecure teachers who valued their authority to the point of thinking themselves infallible. Questioning such authority figures is an infraction in itself, regardless of its legitimacy. It also brings me back to a feeling that I commonly had in reading Gerber’s Howard the Duck: that he uses the comic as a form of catharsis for his own feelings of being misunderstood and precocious as a child. I first brought this up in my examination of Howard the Duck #4, when both Howard and a supporting character are described as brilliant individuals for whom the structured environment of schools were a detriment. It makes me wonder if this theme is notable in Gerber’s other comics, like the Defenders.

Despite my tendency to smirk at these special snowflake self-conceptions, I think Gerber is right that often the attitudes of teachers entrenched in institutional systems meant to shape students into compliant citizens can be more dangerous than the direct violence of bullies. That being said, the last time we see John in this issue he is about to get his ass beat good and hard by Nick and his buddies in the boys’ bathroom, when they are convinced the two nerds ratted them out to the principal.

El Gato at the funeral for Teresa’s mother.

The Eschatology of Omega

At this point what interests me the most about these two series is their overall serialized form—something I can’t say much of any significance about until I’ve read all the issues of both. The typical Bronze Age comic framework Omega the Unknown volume one seems to adopt with this issue is jarring to me. It is all the ways that the comic defies conventions that makes it a delight. To provide a little context, I think early Ditko/Lee Amazing Spider-Man is an example of such a delight because of how it too defied the superhero conventions of the time, but in the case of Gerber/Skrenes/Mooney’s Omega, they are de-centering the superhero figure even further. To fall into the two-issue villain of the month(s) structure so common to books of the era seems like a weird, if not predictable, choice. We’ll see.

In 2008, things are getting so intensely convergent that issue #4 feels more like the eighth or ninth issue of the 10-issue series. Still, while I am still not sure if this series makes sense outside of its source material, I am enjoying it more and more with each issue, despite its problems. In both cases, despite how different in visual style the two volumes might be, the art is fantastic and really keeps the work afloat.

Omega speaks!

Previous | Index | Next

Share this: