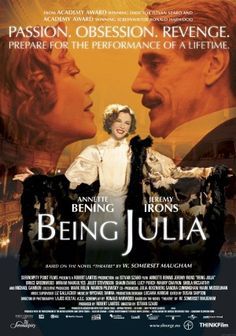

From the description of Being Julia, I didn’t get my hopes up very high. It sounded like a mildly interesting period piece, probably decent quality but not something that would make all that great an impression on me.

In the end, I’d say it held my interest as well or better than the average movie I see, and modestly exceeded my modest expectations. It’s a clever, professional, well-acted film. Its story is OK, but its characters are better. These are entertaining people to spend some time with.

I suppose it’s closer to a comedy than a drama, but it’s more of a light, fun, realistic or nearly realistic tale, than a laugh-out-loud wacky comedy.

Based on a Somerset Maugham novella, Being Julia is set in 1938 London. The protagonist is Julia Lambert, a celebrated—but, she fears, aging (she’s in her 40s)—stage actress. She has a deceased mentor who occasionally appears to her in fantasy form, a husband who runs the theater where she primarily works, and with whom she has worked out a relationship where they will remain largely cooperative and civil with each other even though the passion and sex are gone or nearly gone from their marriage, and a son of about 18.

Among the supporting characters that I most got a kick out of are two we meet early. One is Julia’s personal assistant (or whatever her job title would be—she assists in various ways both at home and at the theater) and the woman who apparently provides the bulk of the financing to keep the theater running. The personal assistant is a wise, cynical, but in her way caring sort I found quite likable. The investor is an ultra-proper British grande dame, but evidently a hilariously lesbian one, who somehow just happens to drop in on Julia whenever there is reason to expect she might be fully or partially unclad—e.g., receiving a massage or some beauty treatment.

Anyway, into Julia’s life, and the life of the theater, comes Tom, a young American lad barely older than her son. Hired by the husband for an accounting job with the theater, he is starry-eyed and worshipful when in Julia’s presence, coming across as a naïve but lovable Yank bumpkin, interspersing his declarations of adoration with plenty of “goshes” and “gollies.” Julia decides she rather enjoys the status his attitude bestows upon her, and soon they are engaged in a hot and heavy affair.

Well, I won’t go into the rest of the story, but it develops at a good pace, is easy to follow, has a few laughs, and gives you a few things to think about.

The deeper it gets into the story, the clearer it becomes that some of these characters are not as they present themselves, though I wouldn’t say one can always know precisely how large the gulf is between what they are and what they pretend to be, nor precisely how conscious and intentional any such deception is.

Consider Tom, for instance. The Tom we meet at the beginning of the film, and the Tom of the second half of the film are certainly considerably different. But is that because his whole “aw shucks” persona was an act, all part of a plot to seduce Julia, benefit financially, or both? Is it because he himself has genuinely changed, that he really was quite naïve early but hobnobbing with Julia and the London theater crowd has turned him into a social climbing playboy snob? Perhaps some combination of both?

Indeed, I’d say the message of the movie is that everything is an act, that we are always “on,” always being careful and strategic in what we say and do so as to influence others in the ways we desire. The spirit of Julia’s mentor tells her this explicitly. He says it is a misconception to contrast “real life” with the theater, as if pretending to be something we want others to think we are is something “unreal” that only takes place on stage. No, “all the world’s a stage,” so nothing can be more “real” than acting.

Certainly there’s a fair amount of truth to that, but I can’t go all the way with it. I can’t endorse the notion that playing a role like that is both ubiquitous and unobjectionable.

I agree that it’s incorrect to assume that being real with people and showing your true self is the norm and that projecting some false persona from pragmatic motives is the exception. But what I would say instead is that these things are matters of degree, and that being real in how we deal with people is an ideal that we rarely if ever achieve perfectly but can approach with varying degrees of success in different relationships in different circumstances.

Though there are times that the strategic, manipulative pretending practiced by the characters of Being Julia is humorous, there are also times (sometimes the same times) that it is disrespectful and cruel, including Julia’s performance in the climactic scene, which is celebrated by most of the other characters and surely intended to be one of the funniest scenes of the movie, but that for me also has a creepiness to it.

There’s a scene in which Julia’s son tells her of a hurtful and disillusioning experience he had in childhood, when he recognized that something seemingly heartfelt and spontaneous that she told him was in fact word-for-word some lines from a play.

Apparently whenever she felt that what her little son would react most favorably to would be a certain persona (that of the wise advice-giving mother, the caring, nurturing mother, whatever), she would search the database of her mind, find a character that sounded like that, and perform that character.

She seems to see nothing problematic in this, and my impression—I may be wrong—is that Being Julia takes that same position, but my gut reaction is to agree with the son.

I mean, I can see it both ways. At some level I suppose Julia’s mentor is right that we’re always performing. Even when we’re being as sincere as we can, the ways we express our ideas and emotions are the ways we’ve seen (or heard of or read of) others doing so. That’s just how socialization occurs and influences people; that’s how we develop our ability to communicate. So in that sense I guess it’s all imitation at some level, it’s all adopting the role we choose to adopt in the given circumstances.

But it still just seems to me that some distinction can be drawn, that even if in some sense to some degree everything we do is an act, that’s not the case in every (morally relevant) sense to an absolute degree. I still think we can and should strive to be real with people, and that one of the potentially most valuable things about a relationship is when there is the level of trust and mutual respect to be open and honest in that way.

A person who dismisses all that as naïve, impossible, or not valuable has a certain sadness or loneliness to them, an emptiness of the soul. That’s what I see in Julia. Though I think she’s a more sympathetic character than not, and I find her likable to an extent, I’m also sad for her.

All the world is not a stage. There is a world beyond phoniness and playacting that deserves to be called “real.” Insofar as you partake of that world—however imperfectly—you connect with other “real” people, and that’s far more valuable in the end than sharpening your acting skills.

Advertisements Share this: