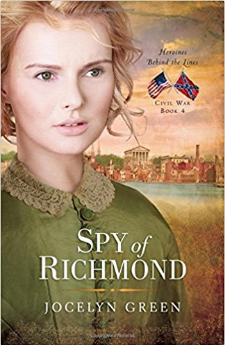

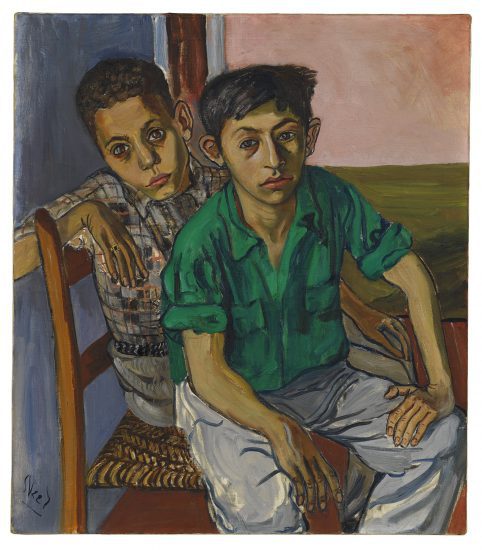

Alice Neel, Two Puerto Rican Boys, 1956

Oil on canvas, Jeff and Mei Sze Greene Collection. © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London and Victoria Miro, London

An unintentional side effect of the recent uproar over the inclusion of Dana Schutz’s Open Casket in the Whitney Biennial is it raised important if seemingly self-explanatory questions about how white artists should ethically represent people of color and their experiences. And no, I’m not praising its ill-conceived inclusion as “opening a conversation.” I’m sure we could have opened a conversation without ignorant curation. But, immersed within the debate for weeks, I couldn’t help but approach David Zwirner Gallery’s current Alice Neel exhibition Uptown thinking of Dana’s garbage painting and her morally dubious artistic decisions.

A collection of Neel’s portraits of people of color from her two neighborhoods of Spanish Harlem and the northern Upper West Side, the racial breakdown of Uptown is similar to Dana–a white lady depicting bodies of the “other.” While clearly a less traumatic subject matter than Emmett Till, it’s a tensely problematic power dynamic nonetheless. Neel’s paintings and the show itself could easily become the old favored standard tale: singular white artist bestows their gaze on people of color. Lucky them! What an angel!

However, this was not the case. Curated by Pulitzer Prize-winning critic and one of our Filthy Dreams favorites Hilton Als, Uptown exemplifies both how white artists can create compassionate portraits of people of color without feeling exploitative or objectifying. But, the show succeeds not just because Neel painted portraits of people of color with humanity (a rarity then as now), but also because Als makes a point to emphasize the lives of Neel’s subjects as well as that of the painter. Uptown essentially is a how-to guide for curators on centering minority voices and accomplishments in order to counter the dominant white supremacist art historical narratives. Thankfully, here, Neel is depicted as a participant, supporter and documentarian of a vibrant polyvocal community.

Alice Neel, Mercedes Arroyo, 1952, Oil on canvas, Daryl and Steven Roth Collection. © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London and Victoria Miro, London

The exhibition is almost entirely portraiture, with the exception of one landscape painting. Neel’s choice in sitters was inclusive–not restricted to other creatives or intellectuals. Neel’s range of subjects immediately hits viewers as soon as they enter the gallery. On one wall in the 525 West 19th Street space, there’s a painting of Mercedes Arroyo, a Puerto Rican social activist. Across the room is Anselmo, a neighbor of Neel’s who helped her around her apartment. Neel’s democratic choice in sitters continues throughout the two exhibition spaces with representations of artists, activists, playwrights, writers, taxi drivers, children and anonymous sitters. It looks like Neel would paint anyone and everyone (There’s even a cute story in the annotated checklist about two neighborhood boys who asked, “We hear you’re painting some Spanish children. Would you paint us?” She did).

This is further emphasized by the show’s organization, which is split between the two galleries according to Neel’s address. The 525 space features works made at 8 East 107th Street and 21 East 108th Street where Neel lived from 1938 until 1962. Likewise, the 533 gallery presents pieces from 300 West 107th Street. By separating the show in this manner, Als gives viewers the opportunity to see how place influenced the development of Neel’s portraiture.

Alice Neel, Anselmo, 1962, Oil on canvas, © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London and Victoria Miro, London

For example, earlier works, made in Spanish Harlem, are more dark and expressionistic. Part of this has to do with the time they were made in 1940s and 1950s during the height of Abstract Expressionism. As seen in Anselmo, Neel paints her neighbor in front of an amorphous yellow background in varying colors of canary yellow and mustard. To his right is a patch of green splotches that match his green striped sweater. This visible hand of the artist, though, disappears in Neel’s later Upper West Side work. Her color palate and backgrounds brighten–a product, according to Als’s wall text, of the increased light in her new apartment.

The demographics of her subjects also change between neighborhoods. Her earlier work represents mostly black and Latinx sitters, while post-1962 paintings begin to feature more South and East Asian subjects. This change in ethnicities asserts Neel’s intent to depict her surrounding community rather than using the sitters’ races and ethnicities as a political tool. Her focus simply switched with her move. While, on some level, all representation of people of color by a white artist is political, but Neel’s portraits of her friends, neighbors and community members don’t feel purposefully ideological.

Alice Neel, Ron Kajiwara, 1971, Oil on canvas, © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London and Victoria Miro, London

And this, as Als writes, “was unusual and is still” (16). Als, in the show’s catalogue, even attributes her decision to paint her community as an explanation for her struggles early in her career. What a surprise. He writes: “Had Neel restricted her canvas to the white world, she would have been celebrated sooner, swear to God, because then her detractors, or the people who ignored or marginalized her, would have seen themselves, which, in the art world at least, is always rewarded” (16). At the time of Neel’s earliest portraits in the 1940s and 1950s, people of color were either not represented at all (Think Invisible Man) or restricted to social realist depictions in which people of color were generic political symbols.

And even today, as Als explains, “The truth of the matter is that many—most—contemporary artists of non-color are interested in reflecting themselves, their creamy whiteness and hair untroubled by thought. On the flip side, many artists of color who make a buck nowadays do it by equating blackness with oppression and selling the result to white people without feeling a thing for their subjects’ lives. Neel’s work smashes both of those categories, showing us the humanness embedded in subjects that people might classify as ‘different'” (16).

Alice Neel, Alice Childress, 1950, Oil on canvas, Collection of Art Berliner. © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London and Victoria Miro, London

Rather than using the bodies of her sitters for her own political purposes, Neel’s portraits portray her palpable interest in the sitters and their individual modes of self-presentation. Take, for example, the juxtaposition between Ballet Dancer and Alice Childress. Ballet Dancer is a picture of relaxation. The young man lounges on a blue sofa, head in his hand, staring off into space. His body bears the marks of his profession with his long, lithe limbs, sleek black outfit and slightly wonky toes, perhaps gesturing to the dancer’s likely bruised feet. In contrast, Childress, the playwright, sits with a proper posture, gazing out a window with her head in profile. She wears a strapless blue striped dress, a large golden medallion necklace and a vibrant red hat. With her head turned to the side, Childress appears ladylike and elusive. The two paintings could not be more different and yet, what joins them is the care given to representing the two subjects’ distinct physicality.

Beyond the care Neel took in faithfully representing her sitters, what makes the exhibition feel, on some level, anti-hegemonic is the emphasis Als’s places on educating viewers about the sitters in Neel’s paintings, as well as their place in the communities in which the artist lived and worked. By presenting the accomplishments or lives (when known) of those in the portraits, Als asserts the creativity and thought of people of color beyond just bodies in a painting.

Alice Neel, Ballet Dancer, 1950, Oil on canvas, Hall Collection. © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London and Victoria Miro, London

He accomplishes this through an annotated checklist, including short biographies of many of the subjects, and three vitrines full of books, photographs, records letters and other ephemeral materials related to both the paintings’ subjects and Harlem at the time. Granted, a checklist seems like an almost laughably minor detail in exhibition organization. But, it made all the difference in my viewing experience. Rather than just regarding Neel’s skillfully rendered portraits, I read and learned about the individuals in the paintings–many, I’m embarrassed to say, I didn’t know before like Horace Clayton. More than just a suit-wearing man covered in shadows leaning back contentedly in a chair as represented by Neel, Clayton was the co-author of Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City, a seminal text on race that traced the history of Chicago’s Southside.

Selected books written by Alice Neel’s subjects and other related publications and photographs chosen by Hilton Als, Alice Neel: Uptown, at David Zwirner New York, February 23 – April 22, 2017.

© The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London and Victoria Miro, London

A vitrine in the center of the gallery features a copy of Black Metropolis, along with The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual by Harold Cruse and A Hero Ain’t Nothing But A Sandwich by Alice Childress (both of their portraits hang nearby). By literally centering the work of the people in the paintings, Als, like Neel, affirms the existence and cultural importance of these often overlooked subjects, without resorting to using their bodies as appropriated tools for whiteness a la Kelley Walker or our old friend Dana. Even though Neel’s work is still the main focus of the show, Als’s organization emphasizes that she was one artist among a community of thinkers and creators who are all worthy of the viewers’ attention.

Share this:

![Two Masters for Alex by [Thompson, Claire]](/ai/026/272/26272.jpg)