by Seb Patrick

by Seb Patrick

Those of us who have an investment in comics, and in their continuing health as a medium and an industry, often find ourselves looking at how successful – or, more often, not – they are at appealing to new readers. It’s common to criticise ongoing Big Two comics for being impenetrable and arcane; reliant on too much pre-existing knowledge to ever be able to jump onto a current series without having a fully immersed grounding in everything that’s gone before. It’s a problem of long-form serialised fiction, allied to a problem more distinct to comics which attracts, as creatives, the kind of people who are already inclined to obsess over their minutiae and vagaries and thus perpetuate them.

And yet, people do discover comics afresh for the first time. They do so all the time. Maybe not in as great a number as they used to, but they still do all the same. If you’re reading this, you probably like comics – so you probably had a “first comic” that hooked you in. And chances are, it wasn’t a shiny new-reader-friendly #1 that opened with a recap page explaining exactly who its lead characters were and their life stories up to that point. It was probably an issue #37 or a #234, the third part of a four-part story, or an annual that was part of a line-wide summer crossover.

Of course, I’m not saying comics shouldn’t make any kind of effort to engage with new readers. Regular jumping on points are a good thing, as is clear storytelling that doesn’t rely on too much assumed knowledge. But at the same time, we don’t always have to assume that someone picking up a comic for the first time is a moron – whether they’re seven years old or forty-seven, the chances are that if it’s a good comic, they can get something out of it and want to come back for more.

I know that many of the first comics I read as a kid in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s were random DC and Marvel issues that were part of longer-form continuity, and were sometimes heavily rooted in it, but which I was able to pick up and enjoy on at least some level. And in a time before Google, I was still able to start to learn enough about these universes to be able to understand their wider context more and more (although, full disclosure: when it comes to DC I was able to cheat a bit thanks to my dad also collecting the Who’s Who binder series).

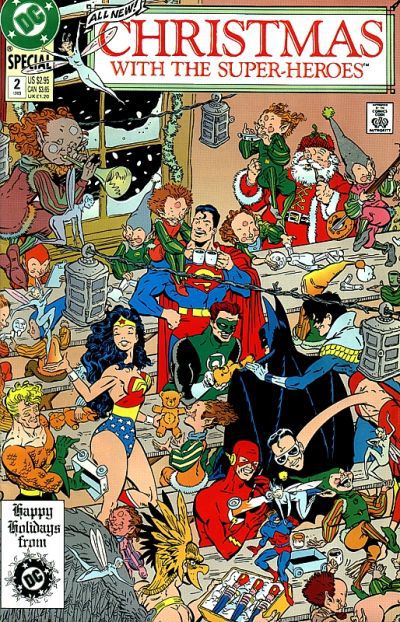

Christmas With The Super-Heroes #2 is definitely one of the first DC comics I remember reading. The copy that’s sitting alongside me right now is not the one I originally owned, and I don’t know where or when I originally got my hands on it – although it was likely within about a year of it first being published in 1989. It’s one of DC’s classic festive-themed anthology issues, telling several short stories based around different characters, with wildly differing tones and themes. And it’s a classic example of a comic that is, in places, absolutely heavily rooted in existing continuity and context while also being entirely possible to enjoy outside of it.

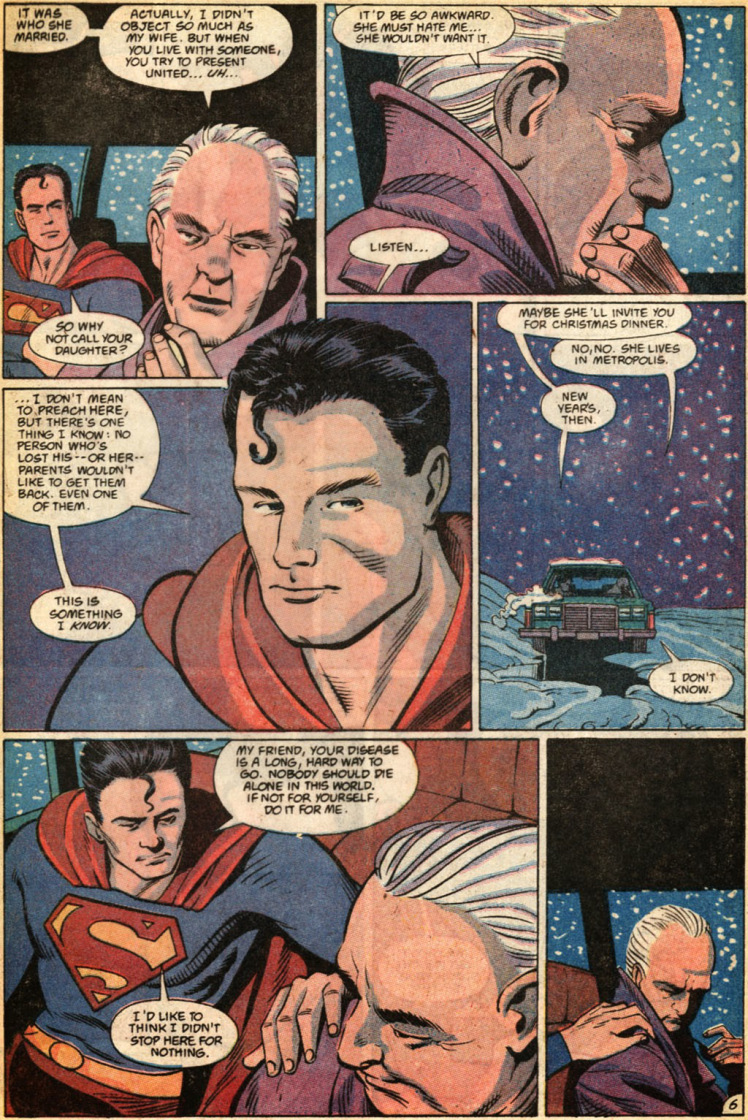

Its opening story, Ex Machina, is a pretty big deal, as it sees the writer/artist of then-indie-darling-hit Concrete Paul Chadwick telling a sweet and sad vignette about Superman talking a depressed man out of suicide in a broken-down car in a snowstorm. Its resolution relies on an the reader drawing a certain inference – but you’d have to be completely unfamiliar with Superman lore not to realise that the couple he’s talking about are Ma and Pa Kent. Even if you are, you can take his description of them to the driver (“they help me sometimes”) entirely at face value and it still works. The core of the story – Superman trying his best to help someone in an unusual, and possibly still ultimately quite hopeless, situation – still resonates.

When I first read this, I wouldn’t have known much about Paul Chadwick’s work – although my dad was a Concrete reader at the time so I was dimly aware of it – but having devoured reprint editions of the (sorely underrated these days) series in recent years, I can see just how well this story fits in with Chadwick’s general tone and style. None of this is necessary, of course, to understand the story in and of itself, but it does enhance it.

Another of the stories centres around Enemy Ace. Do you know who Enemy Ace is? I’m not sure many people do, unless their names is Garth Ennis. The character was a German First World War pilot, who became popular in backup stories in Our Army At War in the 1960s, which were distinctive in telling the “other side” of the story with sympathy (the Ace himself, Hans von Hammer, was presented as an honourable and chivalric man). But this silent tale of an uneasy Christmas truce, created by John Byrne and Andy Kubert, doesn’t need you to know any of that at all: it gets across everything you’d need to understand it purely with its visuals and body language (von Hammer’s uniform helps here, of course).

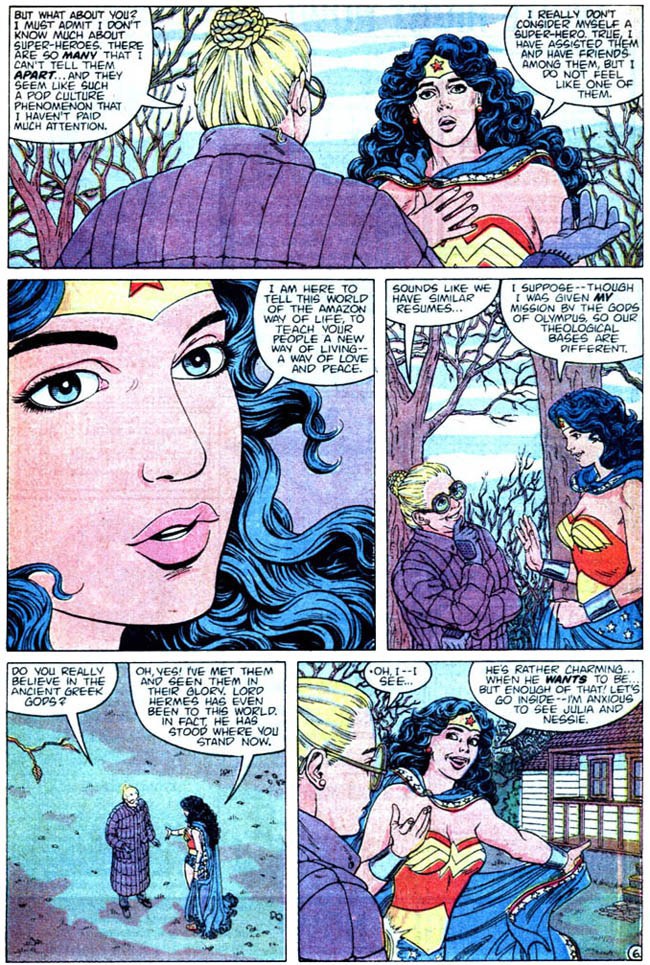

Somewhat more rooted in the then-nascent post-Crisis continuity is the Wonder Woman story, written and (beautifully) drawn by Eric Shanower. If you weren’t already following George Perez’s Wonder Woman, which was around two years into its run at the time, you might not be familiar with the supporting characters that the story predominantly focuses on – I know I certainly wasn’t. But their relationship with Diana is well laid-out in the limited page space, and we’re also introduced to her afresh through the eyes of a visiting pastor suffering a crisis of faith.

The story itself is slight but there’s a strong understanding of the character, particularly with her declaration – delivered sadly, rather than as an heroic pronouncement – that “I believe in love and peace – to enjoy and truth…”

There’s also a Dave Gibbons-penned Batman story – again, a creator I wouldn’t have been aware of the significance of in 1989 – and a fairly straight-down-the-line, out of continuity Barry Allen Flash and Green Lantern story by Bill Messner-Loebs and Colleen Doran that certainly doesn’t require any prior knowledge (aside from helping you get the gag at the start of Ollie buying Hal Das Kapital every Christmas).

But the one that’s resonated the most through history – and is certainly the reason this comic is most commonly talked about – is the final story, a Deadman tale by Alan Brennert and Dick Giordano in which the ghostly hero bemoans his inability to enjoy a happy Christmas ever again, and the lack of appreciation he receives for the sacrifices he makes. He’s then met by a blonde woman who explains that “We don’t do it for the glory, we don’t do it for the recognition… we do it because it needs to be done. Because if we don’t, no-one else will. And we do it even if no-one knows what we’ve done. Even if no-one knows we exist.”

If you didn’t already know, the girl disappears after declaring that her name is “Kara” – it’s an unusual, continuity-breaking appearance of the deceased (and written out of history) original Supergirl. If you don’t know this, then surely the story doesn’t have a lot of its power – but does it have any left at all? I’m not certain (and it’s hard for me to judge from the perspective of an enormous fan of Supergirl who is hugely moved by this appearance), but I think it does. I think the Deadman part of the story still works, and I think what “Kara” – even if she is a mysterious stranger, as she is here to Deadman – says is true.

Christmas With the Super-Heroes #2 is a remarkable comic, from a particularly fertile period of DC creativity. Reading it now, as a thirty-year fan of this universe and these characters, I get immense joy out of what it does with several of them – but I also know that it’s a comic that had stuck with me as a pre-teen, when I didn’t have pre-existing knowledge of half of what it was on about, because when I picked it up again as an adult every page was instantly familiar.

I had been able to read and enjoy it back then without any preconceptions, without worrying what else I needed to know about it – and that’s something that I think we can often forget how to do as adults. Maybe we’d enjoy comics a bit more if we let ourselves read them as kids sometimes.

Christmas with the Superheroes #2

by Paul Chadwick, Bill Messner-Loebs, Colleen Doran, John Byrne, Andy Kubert, Eric Shanower, Alan Brennert, Dick Giordano and more.

Published by DC Comics in 1989

Seb Patrick is a writer and editor from Liverpool who has written for sites including CBR and Den of Geek, and works as the web editor for the official Red Dwarf website – a role he has held since 2011. You can find his personal website here, and he’s found on twitter right here.

Advertisements Share this: