If you have a moment to spare away from the futuristic sounds being channeled into your technologically enhanced ears via your retinal interface, I’d like to introduce you to a thoughtful young man from Copenhagen instilled with a prodigious talent for making evocative, electronic music filled with history, memory and uplifting melancholy.

Henrik Koefoed Petersen is a producer/musician who calls himself Erosion Flow; a name that succinctly communicates how he captures the restless flow of the moment in the face of the inevitable, and transforms it into deeply personal, uncompromising dance music infused with spine-tingling flourishes of rave, bass music, house and IDM.

This futurist is of the opinion that Henrik has the required talent, vision and technological wherewithal to create a new musical legacy, and, as the title of my blog implies, I think it might just remain relevant in 2120. Hell, he’s only 23. If scientific research into cell regeneration doesn’t get derailed, he’ll probably be around when you read this message.

Make no mistake, Erosion Flow is the sound of 2017. And yet, part of the reason that it feels so unequivocally now is its flagrant disregard for the majority of musical developments and trends happening right now. With a deftly calibrated balance between the opposing forces of past, present and homegrown idiosyncrasies, it resonates a moment time in its stubborn, intuitive inconsistency. Also, I probably don’t need to tell you this, but owing to a certain president, culture tends to get politicized in this day and age. Henrik, however, has chosen a different path. A reflective sensibility with an inherently skeptical approach to politicized intent in popular music – despite keen awareness of his privilege and the global music scene’s uneven power structures. Currently signed to Martyn’s 3024 label, the output is, in the rising producer’s own words, ‘music for the people.’ Freed from gimmicks and actively opposed to religious, political and ideological agendas, it is, simply put, very no-bullshit and pretty great.

Central to making music is memory. Interestingly, Erosion Flow works in a giant, collective memory bank. Like a younger, dance music version of the BBC archive-dwelling, documentary filmmaker Adam Curtis, the Copenhagener works part-time in the musical archive of the Danish Broadcasting Corporation where he digitizes formats of old while soaking up the dusty, analogue vibrations of the DBC’s vast, inanimate music recollection.

One sunny Friday in March I went to visit Henrik with our photographer, Anton, in his two music lairs. Starting out in the archives of the Danish Broadcasting Corporation, we had a chat about musical memory, the ethics of sampling and inspirations and influences, finally ending up in his Nordvest studio for a talk about the Copenhagen scene, the politics of contemporary dance music and intuition in the creative process.

So here we are in the musical archives of the Danish Broadcasting Corporation – what’s it like working here as a producer/musician?

Working at the archives really has made me much more humble. Going through all of the different music has put a lot of things in perspective, especially when it comes to credits on music. That’s also why I don’t sample any of the records here either. I think working in the archives has matured my take on music. And the sampling debate, which has been a hot topic for some years, especially the implicit issues of cultural appropriation, had added to that. All that stuff definitely had an influence on the way I now source my sample material, and has made me think a lot more about my personal relation to the sources I draw upon.

That’s why I’m pretty focused on trying to only use sounds that are of a certain personal significance to me. I still think sampling is great, but I’ve just come to a point where there’s no sense in sampling random stuff; there has to be a connection to the sounds I use. Lately I’ve been running my iPhone through synthesizers, and I’ve found a lot Youtube-clips from stuff like the And1 Basketball Mixtapes and video game interludes, which traces memories back to when I was growing up, so it creates a nostalgic aura in the tracks. Even if it just floats very subtle in the background, it still evokes a lot of emotion for me.

Did you follow the appropriation debate around Jamie XX and Romare and their use of samples?

Yeah, I did read that stuff. I must say, that I’m in no way the right person to judge, since I don’t know either of their personal relation to the music they’ve sampled. But those incidents, definitely made me reconsider how I personally went about sourcing sounds and samples for my music.

The thing is, that most of the people I know making club music today are, like me, from Caucasian, middle-class, suburban backgrounds. And when I started out making music as a teenager, I didn’t have the knowledge about where the records I sampled were from, or what the history behind them were; I only went after the sound and to see if I could add something extra to the track I was producing. But today I feel very different, and I wouldn’t let myself source anything directly from another artist, to benefit my own music.

I think it’s important that the people doing that also stand accountable and acknowledge where the original comes from.

Does the kind of music you work with here at the archive influence you?

It’s hard to say if there’s a direct influence. I think it’s more of a subconscious thing. It’s inspiring in the way that you’ll stumble across stuff that has a completely different approach to music, than that of my own. For instance I have been digitalizing a lot of the Folkways Records music, which is an American, state-subsidized initiative from the late 1940s created to record and preserve music from around the world, especially tribal music from lesser technologically advanced places on earth. That thing really blew my mind, as to how you can look at music so differently, due to your cultural background and heritage. And even though local hotbeds around on the house and techno scene still exist today, in a broader picture, there is so much stuff you can’t differentiate because everyone is pretty much using the exact same soft- and hardware.

In the studio.

If we talk about different formats a bit, vinyl has experienced a resurgence, and other obsolete formats like cassette tape are rearing their heads. What’s your take on that?

It’s great that people are pressing vinyl and that the pressing plants are keeping busy! I hope that more will follow to open and that it’s not a short-lived resurgence. But for me personally, it’s never really been about the formats, though. I enjoy playing vinyl when out DJing, but my own releases have always been available digitally as well, and I will continue to make them available. I want my music to be accessible to everyone with an interest in it. And I guess I believe too much in technological determinism to only release stuff on vinyl. I do have a proclivity for nostalgia, but that’s much more about personal experiences. That’s also why I think it’s interesting to use the contemporary, digital hell of Youtube and stuff like that for sourcing sounds, even though many would argue that the sound quality is much better through vinyl- or tape compression. But I think it’s interesting to use current technology, and not romanticize the sound of now.

Youtube is an interesting topic. In his book Retromania, Simon Reynolds makes the case that the platform has played a central part in creating a generation of creatives obsessed with the past by enabling them to make 1:1 copies – by looking at videos as opposed to the creative output that comes from misremembering influences. What’s your take on that?

For sure! YouTube is an extremely efficient portal when it comes to tracing down the ins and outs of any type of production, and it has also been key for me when I started making music. But I agree that there’s definitely a flipside to that. There’s so much music simply trying to recreate the past that is being put out, especially within house and techno. But regarding that, I also think it has a lot to do with the origins of the genres being so closely connected to specific hardware. Like the fact that you could easily create a simple Chicago/Acid House track if you were to get your hands on a 303, 808 and a M1 or even if you found some reasonable digital duplicates of those machines and then found out how to make the “correct” rhythmic patterns, chord progressions, etc.

That thing is definitely hard for me to see the point in; not wanting to risk anything and simply putting the least amount of personality into the music.

In your own music, you sometimes use elements that could be considered classic. What do you get out of that?

I’ve pretty much grown up using what I have had at my disposal. I’m very fortunate to be in a studio, where some of my friends have a lot of vintage gear I can use as well. But it’s never about recreating certain sounds I’ve heard before, it’s much more about digging a bit deeper by blending different sonic textures both digital and analog, and trying to create something unique that also captures the vibe and the feeling I’m having when in the studio. In that way I like to see it as a reconceptualization of various elements from club music’s past, put into a new context.

How would you describe the scene in Copenhagen?

To be honest, I’m probably not the best at participating in it – but from what I see, hear and the parties I go to, it seems like it’s pretty healthy at the moment!

For me it’s always been about creating my own bubble. This bubble pretty much only includes my close friend Andreas (producer for Saint Cava – ed.).

I’ve learned that if you let too many in, you might lose your focus. It can end up taking the wind out of your sails, and you can loose track of the vision you had from the beginning. I think it’s about creating a balance where you are in a comfortable environment to create independently, but remain susceptible to impressions with a critical sense, so you can actively select the ones that are useful and inspiring to what you’re doing. Growing older and getting more mature has definitely helped me establish the right balance.

There’s seems to be a carefully tuned balance between melancholy and euphoria in your music. I guess you could call it uplifting melancholy? Is that something you actively strive to work into the music – is it something you’re aware of?

That’s a very hard question. Because it’s down to the feeling I have and the atmosphere I’m in when I write the music in the studio. Something I’ve learned from working with Martyn and releasing on his label was that energy is paramount when it comes to club music. But regarding the melancholic elements, I guess it has become a defining characteristic of my music – it’s just the vibe I’m into. I realized that when I made ‘Syvv’ last year; But I like to think it’s more of a withdrawn, reflective kind of euphoria. I think that’s pretty close to my personality. I’m more the reflective type and I need some kind of emotional triggering in music, otherwise it’s quite hard for me to respond to. Making techno tools, even though I love playing them, just isn’t for me. I need to cram as much personality and emotion as I can into my music.

Does the melancholy thing have anything to do with the general state of the world? Do you get influenced by what’s happening around us?

That’s the kind of question that everyone wants to say yes to at the moment, I feel. I mean, of course I’m aware and I definitely think that those emotions are in everyone’s subconscious. But personally, the only political agenda I have is to get my music as far away from politics as possible in a sense. My music is for the people; it’s really not about politics. It’s created as a free space, where all of that can be forgotten for a moment as cliché as that may sound.

Personally I’m quite opposed to religion and ideology, but I respect people living their lives how they want, of course. I’m just personally more into technology and I think that plays a much more important part in affecting positive change for the future.

Why are you called Erosion Flow?

After loosing my old laptop and all of my music after a burglary, I kind of shifted into a different mindset regarding music. There needed to be more focus, instead of just making tracks with no purpose or no personality. This was around the time when I went out quite a lot in Copenhagen. While we were out, I suddenly started thinking that I’d like a name, which reminded me of that fact that I needed to roll on and keep things fluid somehow. It’s actually the closest thing to a spiritual mindset for me, I guess. If I have any kind of religion I follow, that’s it. So it became Erosion Flow. Erosion is a naturally occurring phenomenon that just happens, and I juxtaposed it with flow, which has these technological connotations – like media that just keep going. It’s not because I want to make it into this huge thing, but it has actually given me a lot in terms of creativity and perspective. In the end, I try to make music in a flow without getting caught up in minor, unnecessary details.

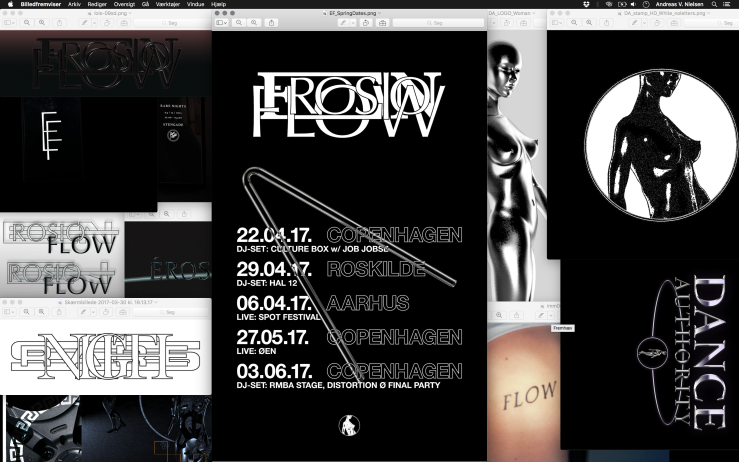

Erosion Flow artwork by Andreas Vasegaard

Erosion Flow artwork by Andreas Vasegaard

www.soundcloud.com/erosion-flow