Today marks the US release (UK fans have a gruelling wait until July) of Black Mad Wheel – Josh Malerman’s long awaited new novel.

There are few authors whose work we can say we adore to the point of avidly and eagerly anticipating every ounce of their output. Josh is the primary example of this. His work overflows with intense mystery, intelligent horror and an alluring sense of wonder, marking him out as a truly unique voice in modern literature.

Whether you’re as madly in love with Josh’s books as we are, or whether you’re yet to delve into his works (if so – start with Bird Box), join us as we sit down with the man himself, to pose him questions both personal and precise.

What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

Tough one. The easy answer is, “The first time Mom spoke to me.” Or maybe the very first words the doctor said, “It’s a boy!” Maybe those words sparked a lifelong love affair with words and putting words together and how something even as simple as it’s a boy could mean much more because the real declaration ought to have been, “It’s so much more than just a boy!” It’s a complex living being that’ll feel and feel big, dream and dream big, until he reads books and thinks he can write them, until he begins interviewing himself about those very books, pretending questions were asked, and until he sits in his office, actually answering actual interview questions that are much more interesting than those he once invented.

I remember the first book I read, I remember reading it, a present from Mom and Dad, and how I unwrapped the book (something about crabapples in a tree and the animals that wanted to eat them) and read the book front to back and how Mom and Dad appeared genuinely stunned. He knows how to read! That might be the most powerful statement I’ve ever heard. Changed me at molecule one. And not just the words, but (as you say) the power behind them. It was good that I knew how to read. I was encouraged to read more. And from there? An affair that I wouldn’t give up for all the riches on Earth.

Can you describe your creative process? Such as any creative routines or rituals you might have. What is the most difficult part of your artistic process?

Tough one again. I try to write every day. But that’s just not possible. Sometimes I set word counts but that number changes per book; maybe I’m rewriting another book and can only give 1000 words a day to the new one, or maybe I have nothing else happening and can give it 4,300 a day. I was talking with my manager Ryan the other day about how “thinking about the book” is also work. “Did you write today?” “No. I thought about the book, though.” “Well, maybe that’s even better.” And maybe it is? Sometimes it is. Because it’s dangerous to tell yourself that every time you sit down at the keys you’ll suddenly know what to do, what comes next. That “thinking about it” can really set you up. Haha. I realize how obvious that sounds, but you’d be surprised…

Here’s one thing I do: when working on a rough draft or a rewrite I will work on the book every day until it’s done. So… the rough draft of Bird Box was written in 26 days, a mad dash, in which I’d wake up at 7AM and start writing by 8. Usually around noon I was finished and the rest of the day was occupied with thinking about what would come next in the book, the next scene. Maybe it’s something like being an athlete; you do need to be in “writing shape.” To get there doesn’t take anything more than regularly writing. But this all sounds so… stiff to me. The real answer to the question is, it changes all the time, the routine, but there IS a routine, with each book, any means, anything it takes to write with spirit and to get the thing done.

Your stories are incredibly original and your characters refreshingly authentic. Where do your ideas come from? And how do you keep your characters so grounded in reality while they’re experiencing such extraordinary events?

First off, thank you. Second… where do the ideas come from? There’s no answer for that. I think if you keep an open “story” mind, always seeing things in terms of a possible story, then they come at you all day every day. Why not a story about this interview? Why not an entire book that is one single interview, your questions prewritten, the author responding, growing increasingly afraid of how much you, the interviewer, already knows?

Mr. Malerman, why do you keep looking out your window?

How do you know that?! How do you know I’m looking out the window?!

As goes grounding characters in reality… this maybe comes from how much I love The Twilight Zone and how Rod Serling was able to give us characters in such short time. A sentence or two. Touchstones. Or something like that. I’m not sure. And I’m not sure I want to know!

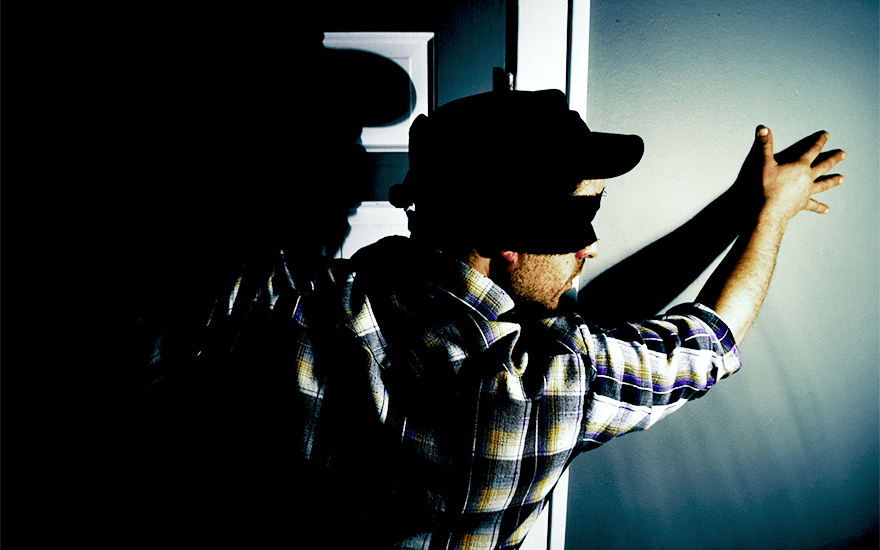

Josh reading, with a horror mask close by.

Josh reading, with a horror mask close by.

Do you want each book to stand on its own, or are you trying to build a body of work with connections between each book?

I’m undecided. I’ve written more than a few stories and books that mention the same fictional cities, mention events from another book, etc. But I’m not sure I’ve set out to write a Faulknerian universe or not. I know this: it’s fun, for readers and writers, too, to reference your other books. Little lights turns on, as if your body of work is one big house and those loose connections give it power, light, A/C. I like when writers do it, and a lot of us do, but I haven’t fully given myself over to that yet. Haven’t married the idea yet.

Do you hide any secrets in your books that only a few people will find?

Shhhh…

Your novel Bird Box is being adapted for the big screen, what hopes or expectations do you have for the film, if any? And are you at all involved in the creative process?

Well, haha, the answer to this is the very article the two of you wrote. That article is verbatim what I’d like to see happen with the movie. I flew out to Los Angeles and met with the producers, talked with them as I leafed through the most elaborate storyboards I’ve ever seen. At one point they asked me how I would approach the creatures. I told them this:

Horror embraces the FIRSTS. Horror fans revere the FIRST one to do this, the FIRST one to do that. FIRSTS. So why not let Bird Box be the first film to incorporate long sequences of just… darkness? Five, six minutes of black? In this day and age, with the sound systems the way they are, why not go dark, cave black, and play with the senses; the Boy on the right, the Girl on the left, Malorie and the sound of the canoe cutting the water in the middle; sticks cracking from behind? FIRSTS. Us horror fans… we’d love it.

After I’d gone through this impassioned monologue, one producer asked me, “So… you’re suggesting we show nothing in this movie at all?”

And I, smiling, said, “Yes.”

What can you tell us about your upcoming novel, Black Mad Wheel?

Black Mad Wheel is about a group of friends, former members of the army band, who are now an instrumental rock n’ roll band in Detroit. They’re heroes around town because they served in WWII and they have a regional hit song in “Be Here.” One afternoon they’re approached by a government man who says they’re needed… turns out there’s a disturbing sound emanating from the Namib Desert in Africa… could the Danes track it down, tell the government what’s making this noise? They’re the perfect guys to approach; musicians and soldiers. So, if you can imagine boom mics instead of guns, reel-to-reel machines instead of tanks. I’ve got a silent pact with myself that, unless the book is a western, unless the violence is “cartoonish,” I don’t want any gun death in my books. Too much gun violence all over the place. To me, a fella like Tarantino isn’t a bad influence on society whenever his movies dissipate into shoot-em-up endings, but those endings are just boring. Let’s get more creative. If we’re gonna kill our characters, let’s come up with crazy ways. I’m proud of Black Mad Wheel for doing that.

Now, the narrative is split in two. Like Bird Box. And so on the one hand we’ve got the Danes searching the desert for this sound, then there’s the thread in which one of the Danes, Philip Tonka, is healing in a hospital in Iowa. He’s been hurt in a bad way by the source of that sound and as the two timelines slowly dovetail, we get the full story of what happened, what they found, and what Philip has to do about it now.

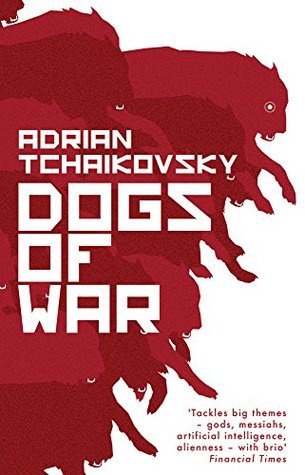

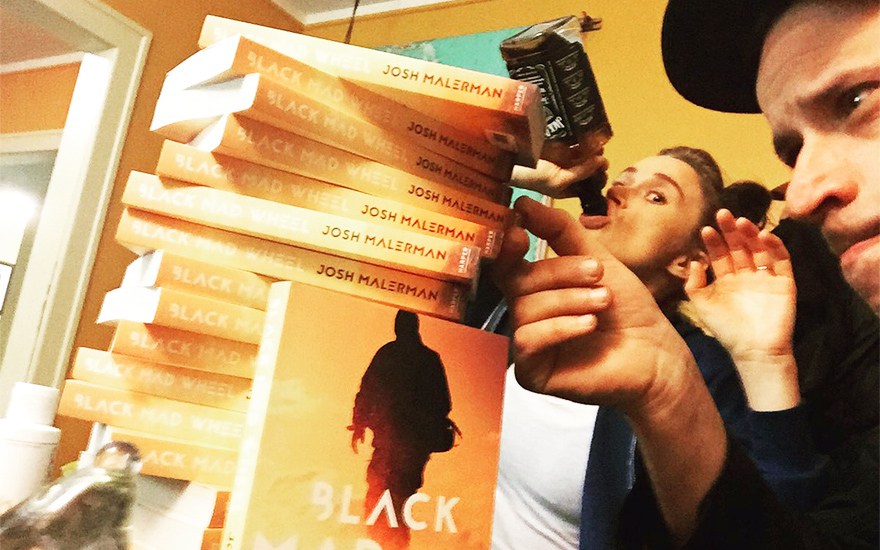

The US hardback version of Black Mad Wheel.

The US hardback version of Black Mad Wheel.

What projects are you working on currently?

It’s a big year for releases: Black Mad Wheel (novel) May 23. Bird Box Special Edition (novel with additional short story and an afterword) July. Goblin (limited edition novel) on Halloween. On This, the Day of the Pig (limited edition novel) probably in December. Then Unbury Carol (novel) is slated for release next April, 2018. And short stories and novellas along the way. I wrapped a new rough draft about ten days ago. When will that one see the light of day? No idea. And I kinda don’t care. I can’t care about that or I’ll go nuts with impatience. I’ve got a shelf of rough drafts, all of which I love as much as I do Bird Box and Unbury Carol, and I’ve gotta quietly hope they all see the light of day in their turn. That’s pretty much how I’ve operated since forever; write write write and let the stories come out in their turn. (But, you know, sometimes it’s fun to force a turn for a book, too)

What’s the best advice you’ve been given? And what advice would you give to aspiring writers or musicians?

Get rid of the words “good” and “bad.” Throw them out. When you’re working on a rough draft, remember that it’s rough! If you spend the whole time classifying every beat, every sentence into YES or NO it’s going to be a grueling road. It’s a grueling road even when it goes well. So that, for me, that’s the big thing. Write with love, with spirit, think about the story when you’re not writing it, and completely eliminate the words “good” and “bad.” That’s just clutter. And if you’re struggling with a street name? A character name? Name the street STREET STREET. And the character MAN. And go fix it when you rewrite it. Because no matter what you write, you’re going to rewrite… and what would you rather have? A stack of paper that needs a lot of work… or no stack at all?

In A House at the Bottom of a Lake Amelia and James agree to ‘no hows, no whys’. This is a conscious choice on their part not to seek the answers to the mysteries that they face. When James does begin to question how, it has a negative impact. This echoes your own choice in Bird Box not to show the creatures or to explain their origin. We also recently wrote an article about how the film adaption should adopt the same tactic. Can we talk a little about this less is more approach? How would you answer those who seek the opposite: to see all of the creatures in their entirety?

There are a couple schools of thought on this; some authors enroll in one or the other, some don’t; either you’re the kind of writer who shows the monster… or you’re not, that whole thing. But I don’t feel that way. For me it’s story by story, book by book. Halfway deep into Bird Box I had to start asking myself if I was going to show these creatures. Is that gonna happen? Should it? I love both schools and I’m enrolled in both. It just turned out that Bird Box and A House at the Bottom of a Lake were from the same school. But I’ve written some 26 books now and most of them aren’t like that. Or maybe it’s split down the middle. I don’t know. The point is, while I understand the merits of less is more, I also love over-the-top absurdity. Simple and straight or kaleidoscopic and bright? All of them. So… it’s never a philosophical debate for me… it’s simply what is the book asking you to do, Josh?

Josh Malerman wearing a blindfold, like the characters within Bird Box.

Josh Malerman wearing a blindfold, like the characters within Bird Box.

In A House at the Bottom of a Lake you utilise the horror genre trope of teenagers having sex being the cause of elevated horror. After Amelia and James sleep together, the horror intensifies. It’s a common trope but here it worked really well (I was terrified). Was the use of this trope intentional? What is it about their union that stirred the owner of the house to react in that way?

Tough one. It’s just a very scary idea, to experience an impossibility immediately after losing your virginity. As if, by having sex for the first time, you’ve altered the laws of physics. Talk about a vulnerable moment. Now, James and Amelia are obviously working with a unique set of circumstances, and to them the house is theirs, so why not… celebrate it? It seemed, to them, the perfect, the only place that could measure up to the moment. And there’s something to that. Here we’ve got two young lovers who’ve discovered a freaky setting… but at the same time, that setting is magical to them… so while it might sound like a dangerous idea, adding freakiness to an already freaky situation (losing your virginity)… why not try it? Screw it. The house is as big a deal as the event. But, in the end, it kind of bit them, turned on them… and yet… can you blame them for trying? I can’t. I don’t.

In A House at the Bottom of a Lake you at one point describe taking photos of an empty house as capturing ‘the truest essence of living and life’. Can you elaborate on this interesting notion? What is it about the lack of life that exhibits its truest essence?

When we aren’t distracted by the actual living-life, i.e. a man or a woman or a dog, etc, we get to see the hidden details of how they do things. As if an unseen magician is always standing between us and anyone we interact with, always using some sleight of hand to direct our attention away from what really matters. Take the dog, for example: let’s say we’ve got the coolest Weimaraner in the world and she’s playing with her toys but we’re so busy talking about her coat, the pink human-ness of her eyes, that we don’t notice the exact toys she’s playing with. Then, she walks away, and we study what she was interested in and we see that one toy is buried for later, one is chewed considerable more so than the others, and her interests become clear. Same thing goes for a big empty house… even one under water. If there’s something living in that house… its interests may be revealed by the layout of the house itself, the number of rooms, the dresses that float throughout. Whatever lives down there, inert as it seems, must be after something, right? Even if that something is only staging a reality in which two lovers might feel comfortable enough to enter. As if the house itself was that unseen magician, fooling James and Amelia…

Some readers come away from Bird Box picturing angelic forms for the creatures, some more monstrous visages. This passage in A House at the Bottom of a Lake struck me as a good way to describe what the creatures in Bird Box might look like: ‘Something so nonsensical that it makes fun of everything else in the world. It’s impossible, but it’s here.’ Focusing on the ‘make fun of’ portion of this quote, there does seem to be some dark humour in the moments where characters finally gaze upon the Bird Box creatures (some of them laugh or smile). Can we talk about the link between whimsy and losing one’s mind? In popular culture there are many examples of this (The Joker, for one). What makes comedy and insanity such great companions, in your view?

I’ve imagined me laughing on my own death bed (I don’t like doing this, but whatever) and I see myself alone on a cot, thinking, that was absolutely incredible. ALL of it. The laughter then, there, is because of how overwhelming life is/was. You hear a lot of people talking about how horror and comedy are two sides of the same coin and while I won’t necessary go 100% there, I understand the conceit. And yet, they are very different. Friends may laugh in your horror movie but you never quite scream in their comedies. I think horror, the real stuff, strikes a chord that not even Charlie Chaplin was able to write for his shorts. Real horror, the great stuff, isn’t laughable after all… it’s actually scary as hell. So who would laugh in such a scenario? Ah well, obviously a madman! Or… someone who simply doesn’t know how else to express the overwhelming fear. Don’t you guys wonder how you’d react if you walked into the garage and saw, rather than your car, a two headed black dog, snarling and mad? What would you really do? In most these flight of fancy I see myself frozen with fear, rooted, and so often I prep myself, telling myself, if ever you encounter the supernatural, remember to MOVE, in any way at all, MOVE, because movement will prove you are not to scared to move…

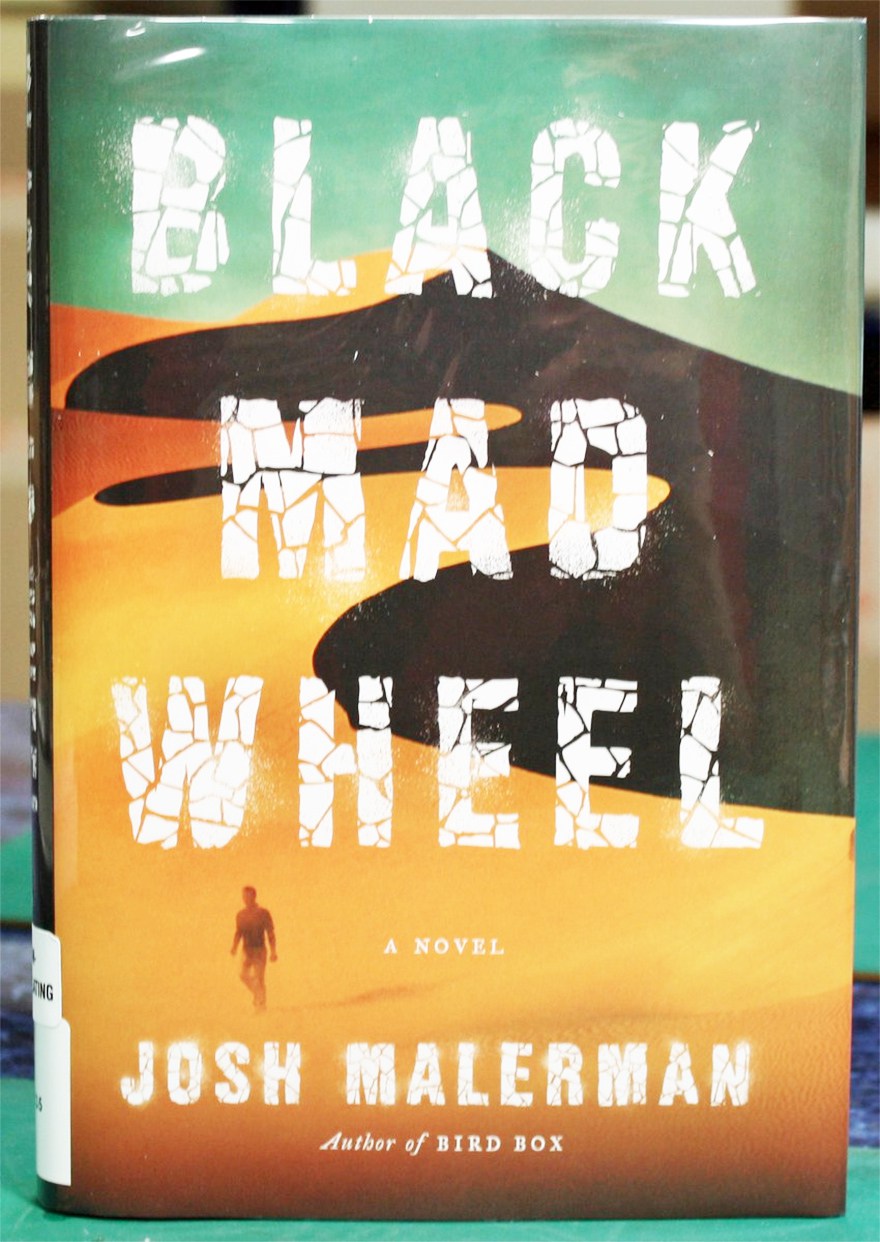

Josh with a pile of the UK editions of Black Mad Wheel.

Josh with a pile of the UK editions of Black Mad Wheel.

Both A House at the Bottom of a Lake and Bird Box examine darkness. In A House at the Bottom of a Lake, darkness is treated as a threat (‘He saw it gripping the beam of Amelia’s light like black hands, black lips, swallowing’). However, in Bird Box darkness is treated more as an ally (‘In her private darkness’). Can you talk a little about the duality of darkness? Did you – like most of us – grow up with a fear of the dark?

Great one. It’s funny, after my mom read Bird Box she pointed out to me that I’d (accidentally, in a way) written an entire novel based on the one thing you want to do when danger is near: look. And yet, the inverse of that is true, also: when you’re scared the one thing you wanna do is… not look. So look, not look… darkness… it all depends on the situation doesn’t it? If I was running from an axe wielding lunatic I might be looking to take cover in an abandoned school, find a dark place to hide. But if I’m fearful that a ghost is haunting me, I’ll probably wanna be somewhere well lit. Depends on the “monster,” depends on the “haunting,” whether it be supernatural or not, and in what ways. Darkness, as you know, can either be a friend (cover) or disadvantage (the thing in the dark with you.)

In Bird Box it is the humans who have to rely on their hearing, while the creatures (presumably) can use all of their senses. However, in A House at the Bottom of a Lake this is reversed: the creature has to rely on its hearing (according to Amelia and James), while the human characters can use all of their senses. Before you wrote these books, did you undertake any research into the audible? Did you speak to any blind individuals, for example, to get their view on using sound to navigate the world?

I wouldn’t say I researched, in the way you’re asking, but I’ve been in a band with my best friends for over a decade so I’m guessing that the “audio” elements to both books (as well as Black Mad Wheel) come from all that time spent in studios, playing shows, making songs. A different way of looking at this might be to look at Alan Yule from Ghastle and Yule. Yule’s films are highly impersonal, or rather, without humans, as in Beastfucker and Bicameral Island. In a way, by cutting off some of the senses from the characters in Bird Box and A House at the Bottom of a Lake, it removes some of their “human-ness.” I think Alan Yule would’ve particularly liked to direct A House at the Bottom of a Lake for this reason, whereas Gordon Ghastle would’ve like it for the spectacle of the house itself and the mood he could create with it. And, you know, of course, most of us have both Ghastle and Yule in us; the spectacle driven wunderkind and the counter cultural artiste.

Horror is experienced through all the senses. You can’t smell a comedy in the dark, but you can smell a rotting corpse down the hall.

This line in A House at the Bottom of a Lake: ‘It was wax… We could have shaped it into anything we wanted it to be,’ to me, feels like a strong summation of how you leave mystery in the hands of the reader. In both A House at the Bottom of a Lake and Bird Box we never get a true answer about the creatures’ origins. I love this approach, as the reader can imagine whatever they like (particularly in Bird Box). Although you can’t give us details, do you, in your own mind, have definitive answers (private wax sculptures, if you will) to the origins of the creatures in both A House at the Bottom of a Lake and Bird Box?

As goes Bird Box, the best I can say is, I know as much as Malorie knows. And sometimes that’s a political answer and sometimes it’s not.

As goes A House at the Bottom of a Lake, I suppose I do see… something. A form… a featureless face… love and obsession and virginity all balled up like silly putty, like when you look at a pile of clothes and can see a face in there, like how sometimes a mop in a bucket might look like a man.

MORE: How the film adaptation of Josh Malerman’s Bird Box should be handled

In Ghastle and Yule two Horror directors are adored and in A House at the Bottom of a Lake Amelia and James adore the house (even calling it their own). In these respects you explore the point where adoration slips over into obsessive worship. Does this come from personal experience? Is there anything that you have adored to the point of obsessive worship?

Many things. Too many things. Everything I’ve ever loved. Just recently I noticed a thread in many of the books I’ve written; the very thing you’re pointing out right now; an obsession; obsessive characters. This was never intentional, I don’t try to come up with scenarios in which characters might become too driven, but they seem to come out that way. I wonder… could be that I’m just an obsessive personality… or… maybe horror and obsession go well together. Well, they do. But maybe by creating an obsessive character you’re creating a living haunted house; a man or a woman with so many creaks and howls that they end up as frightening as the setting itself.

Does the title of your new book – Black Mad Wheel – have any connection to the fictional film in Ghastle and Yule titled ‘Black Wheel of Black Blood‘, even if it is just that their titles were perhaps conceived of a similar origin? Where do you source your inspiration for your titles and your character names?

Great one. Sometimes a title hits you so hard in the head you write a whole book just so you can have that title! Other times you’re halfway through a draft and something a character says sums it all up for you and so… presto… you’ve got a title. There was something of a wink from Black Mad Wheel to Black Wheel of Black Blood yes. Now if we could only get Bill Ferris to direct it…

We can’t thank Josh enough for taking the time to sit down with us. We found Josh’s detailed answers highly insightful, as I’m sure you did too.

Black Mad Wheel is out today in the US and is released on 27th July 2017 in the UK.

Image credits: Josh Malerman, Andres Abdo, Ecco Press, HarperCollins

Advertisements Share this: