The Dead Republic

Roddy Doyle

My mother, encouraging my verbal side, stored my first grade writing assignments in the box my school uniform came in. They’re in my basement now, but one’s missing.

My mother, encouraging my verbal side, stored my first grade writing assignments in the box my school uniform came in. They’re in my basement now, but one’s missing.

Focusing on the core culture our family was built upon, it celebrated Irishness. Its central insight was that …”Merv [Griffin] kiss[ed] the Blarney Stone.”

What can I say? I’ve always been a deep thinker in the social sciences.

Literature, on the other hand, has been known to baffle me. Sometimes I just miss what I’m supposed to see. This time, I’m not certain I entirely grasped Mr. Doyle’s intent but I didn’t miss that there’s something important going on.

Mr. Doyle is Roddy Doyle, a writer I’ve spoken of before and whom I hold in the highest regard. As I said previously, he may be the finest Irish writer of his generation.

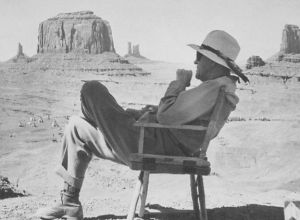

John Ford, 1894-1973

The creator of many iconic American images was born Feeney. That’s just a wee bit Irish.

The present tale is the final installment in a trilogy, the first volume of which I previously wrote about. Together the three novels constitute the story of one life. Well, two lives, really, because the story of the Republic of Ireland seems inseparable from the story of Henry Smart and his family.

I first encountered Smart, in Oh, Play That Thing, as a young Irish immigrant afoot in Jazz Age America, hanging out with Louis Armstrong when he wasn’t revolutionizing advertising sandwich boards. I recall little of the book other than that Henry’s past–which included a wife and the IRA–caught up with him and set him loose in the by then Depression-era American West.

When I finally got to the first book of the trilogy, mentioned above, the back story emerged. Henry wasn’t just in the IRA, he was present at the creation, in the Post Office on Easter Sunday 1916. And he had a whole freight train of distinctly Irish baggage: a bevy of brothers and sisters; a mother who named the stars after her dead children; a peg-legged father–half giant folk hero, half drunken lout–who roamed the streets and sewers of Dublin; even a tubercular brother whom Henry tries to save by taking him along when he flees the homestead.

Just to round it off, there’s a twist on a typical Irish pattern. Henry winds up wed to the first and only schoolteacher he’s ever had, Miss O’Shea, fifteen years his senior.

Maureen O’Hara (née FitzSimmons), 1920-2015

The bicycle is important but so is her attitude.

Henry rises in the ranks of revolutionaries to be a prime fixer and assassin, travelling the countryside on a bicycle, accompanied, as often as not, by a tommy-gun toting Miss O’Shea . Then his number comes up and it’s off to America.

That’s where the director John Ford finds him at the start of this book, peg-legged and prostate in Monument Valley, behind a rock the auteur walked around to relieve himself. Ford, besotted with the notion of doing for Ireland what he did for the American West, hires Henry as ‘IRA Consultant’ to keep things authentic. As described here, The Quiet Man is a very different film from the one I know.

In this telling, Ford is intent on romanticizing the fight to free Ireland from British rule. His chosen vehicle is a story that he will twist into a revolutionary tale. Henry is both suspicious and uncooperative.

One of the intended stars of the picture, Maureen O’Hara, a Dublin native herself, is sent to talk sense to him. Eventually, Henry starts to cooperate only to find himself back in Ireland for the shooting of the film we all know–and one that has nothing to do with his story. He damn near kills Ford before bailing on the entire mess.

The Dublin GPO, rebel HQ during the Easter Rebellion, birthplace of modern Irish myths.

By this point, only a third of the way in, I thought I might be dealing with the Irish version of Zelig. Unlike that fictional everywhereman, though, Henry doesn’t keep turning up in the right places.

Instead he settles down, becoming the caretaker of a new school for boys where he keeps the faculty from indulging in corporal punishment while keeping up the building and grounds. By now, it’s the early 1950s and Henry, born in 1902, is middle-aged. And although he’s lost his family, he seems satisfied to see his nation starting to show signs of coalescing.

The idyll doesn’t last. Henry takes on additional work as a gardener. One of his clients, the widow O’Kelly, seems familiar but denies knowing who he is. Eventually he spends the night. They start keeping house once a week, Henry leaving in the wee hours, tossing his bicycle over the wall. About the time his sleepover friend admits to being his long-lost wife he’s contacted by the IRA.

So the Irish Zelig re-emerges. This time, though, he’s a step removed from the celebs. The Troubles are ratcheting up and Henry is useful to the Provos as an authentic ilnk to 1916 and to the Garda as an ear into the Provisional IRA.

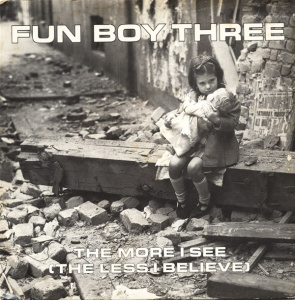

The Troubles spawned more than a few great songs on both sides.

Misidentification lies at the heart of this and you’d think an 80-year-old man has limited uses, especially after Miss O’Shea has a stroke. All he can do is sit by her mute bedside and try to reconnect with his lost daughter. Saorise is now a senior citizen herself and, despite her disapproval of her father’s IRA involvement, has taken on a role of her own.

If I’m not completely obtuse this is where all the symbolism comes together. The Smarts, I think, embody the story of modern Ireland. From the Easter Uprising to the Technicolor tourist-friendly myth-building of John Ford, to the Troubles and the eve and aftermath of the Celtic Tiger era.

It’s no coincidence (although a pretty neat production trick) that in the book’s final lines Henry is on the verge of letting go but is still drawing breath at age 108. You don’t read Doyle for tricks, though. You read him for moments of still beauty, such as this, about a senior member of the Provos: “I watched him bend a bit, to listen for the whisper of the kettle as it got to work.” (p. 312) An entire culture lies within that sentence.

In literature there’s no such thing as a coincidence.

I also think, and this may be Doyle’s real idea, the story of Henry Smart is a rumination on not escaping things that define you as a person or a culture. In the latter two-thirds of the book Henry is always saying “Grand,” a complete sentence that stymies introspection.

There’s a more subtle illustration of this at work, too. The book after all, is the final volume of a trilogy and trinitarianism and the Irish are culturally joined at the hip . But the biggest tell may be the novel’s final sentence. The first letters of each word can be seen everywhere Catholics gather, living or dead.

“I’m Henry Smart,” indeed.

Advertisements Share this: