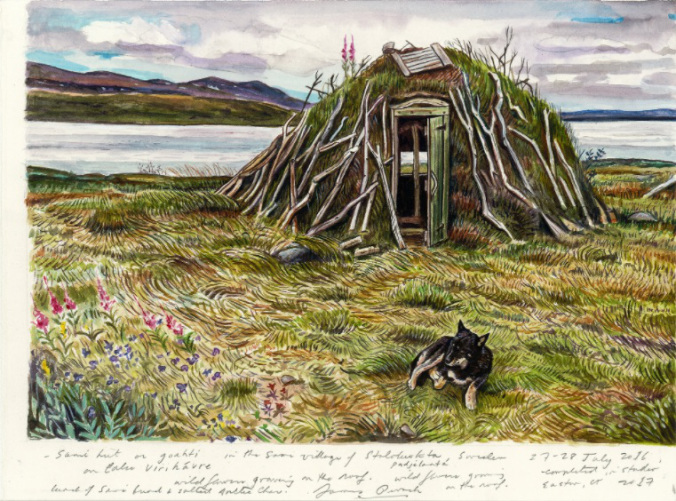

A Sami reindeer herders’ hut on Lake Virihaure in Padjelanta National Park. Credit Paintings by James Prosek, courtesy of the artist and Schwartz-Wajahat, New York

We had a tradition from the moment we arrived in Kerala, inviting some of our favorite people to come see what we were doing there. This one’s work at Cornell was a lovely coincidence because of Seth’s work at the Lab of Ornithology. But mainly, a conservation-oriented naturalist illustrator seemed a perfect fit for what we do. So, seeing what he has contributed to the Travel section of the New York Times today I realize we are due to extend another invitation, this time for him to join us at Chan Chich Lodge in Belize:A Botanist in Swedish LaplandBy JAMES PROSEK

The plan was to retrace part of a journey that Carl Linnaeus made in 1732 when he was 25, from Uppsala, just north of Stockholm, to the northernmost region of Sweden, known as Swedish Lapland. Linnaeus kept a detailed journal of his travels, often called his “Lapland Journal,” with maps of the mountains, rivers and lakes, drawings and his squiggly handwriting.

I came to Swedish Lapland in part to try to get to know Linnaeus better, but also to see if I was judging him unfairly. Linnaeus was the man who invented that clean two-name system, binomial nomenclature, which gave a generic and specific epithet (genus and species) to organisms — like Homo sapiens for humans or Salmo trutta for brown trout. Those names are steady and dependable, but as I grew older and spent more time in nature, I began to see and appreciate nature on its own terms, and learned that it is messy, chaotic and overwhelming and does not always fit into neat categories, as we’d like it to.

I think what bothered me was his hubris. Before binomials, names of plants in books were lists or strings of words that formed a kind of nuanced description. Plants and animals already had names in indigenous languages, and Linnaeus, in a show of imperialism, renamed them with his Latinisms. He believed he could take nature — holistic, fluid and constantly changing — and fragment, label and systematize it. Then again, he lived over a hundred years before Darwin synthesized ideas of an evolving world, and in his view of nature, things didn’t change over time.

By the end of his life, Linnaeus had applied his binomial names to roughly 14,000 species. Today over 1.5 million have been anointed with a genus and species name, and there are said to be in excess of 10 million species on the planet that are still nameless.

On the trip, I was hoping to explore his virtues, among which was a clear and profound love of beauty and diversity in nature, with a particular passion for flowering plants, specifically the ones that grew in his native Sweden. Along with Alfred Nobel, Linnaeus is among this country’s most cherished national heroes. His face is on the 100 kronor note and his favorite flower, which he named after himself, Linnaea borealis, appears on the 20 kronor note.

Linnaeus left for the big adventure of his life on his birthday, May 23 — which also happens to be my birthday — and traveled up the coast of the Gulf of Bothnia from Uppsala toward Finland, making periodic trips to explore the interior. My travel companions and I chose to follow his longest inland route, from the coastal town of Lulea on the Bay of Bothnia, following the Lule River toward the tiny seasonal village of Staloluokta in the mountains, where the indigenous Sami people summer their herds of reindeer.

Linnaeus’s entire trip took over five months, from May to October, and covered roughly 2,000 miles. We had set aside about 10 days last July. At this time of year, Linnaeus had reached the farthest and most remote part of his journey, an alpine region, where he was driven to rapture by the diversity of flowering plants. Today it is a national park known as Padjelanta.

The flora of Lapland had been explored somewhat by his teacher and mentor, Olof Rudbeck the Younger in 1695, but Linnaeus wanted to give a more complete account and collect fresh plant specimens because those collected by Rudbeck had burned in a fire in 1702.

But the main purpose of his trip, as outlined by his patrons at the Royal Society of Sciences in Uppsala, was to discover and record anything of economic interest for mother Sweden (impoverished after the multiyear Northern Wars) — including ethnographic information about the Sami, such as the medicinal uses of plants — not unlike a modern bio-prospector in South American rain forests today…

Read the whole article here.

Share this: