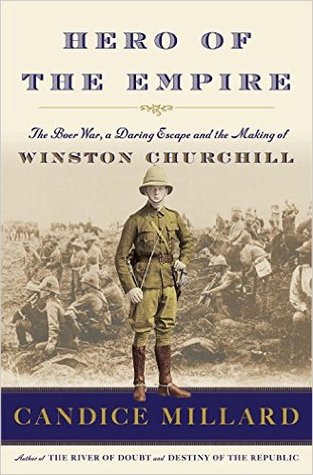

Hero of the Empire, Candice Millard. New York: Doubleday, 2016.

Summary: The history of Winston Churchill’s involvement in the Boer War as a correspondent, his capture, imprisonment and dangerous escape–events that brought Churchill to national attention.

“Crouching in darkness outside the prison fence in wartime southern Africa, Winston Churchill could still hear the voices of the guards on the other side. Seizing his chance an hour earlier, the twenty-five-year-old had scaled the high, corrugated-iron paling that enclosed the prison yard. But now he was trapped in a new dilemma. He could not remain where he was. At any moment, he could be discovered and shot by the guards or by the soldiers who patrolled the dark, surrounding streets of Pretoria, the capital of the enemy Boer republic. Yet neither could he run. His hopes for survival depended on two other prisoners, who were still inside the wall. In the long minutes since he had dropped down into the darkness, they had not appeared” (p. 1).

Candice Millard opens her narrative of Churchill’s Boer War experience with this vivid account of Churchill’s escape from the Boer prison at the Staats Model School. The two other prisoners were unable to follow. With nothing more than a biscuit and a few pieces of chocolate and unarmed, Churchill had to elude capture on a nearly 300 mile journey to Lourenco Marques, Portuguese territory.

Even today, Churchill is known as the Prime Minister who led Britain resolutely through World War 2. We know him as a prolific writer, a gifted amateur painter, and for his sobering speech in Fulton, Missouri about the iron curtain that had descended across Europe. Lesser known were the early events in the life of an ambitious Churchill that propelled him into national awareness and a seat as a member of the House of Commons, setting him on a long, winding course, with many setbacks, to his pivotal role in World War 2.

Millard traces the life of this young man, son of Randolph Churchill, who was a meteor across the political firmament that burned out quickly. He was also the son of Jennie Jerome, a “panther” who would remarry to a man Churchill’s age, but also able to exercise formidable influence to advance her son’s cause, though not formidable enough in his first run for office. He concludes only war experience, with honors, could do that. Previous tours in India and the Sudan resulted only in a memoir, The River War, that served to infuriate some members of the militarily establishment. Conveniently the Boers had declared their independence from their British overlords, and the mighty empire set about to put down this rebellion. Churchill, unable to get a military appointment, goes as a highly compensated member of the press.

Arriving in South Africa, he learns that the war will be no cakewalk. The Boers, eventually led by Louis Botha, are formidable fighters who could strike swiftly, ruthlessly, and then vanish into thin air. Churchill, always willing to risk himself to get the story finds himself on an armored train that was part of efforts to relieve the British defenders of Ladysmith. Instead, the train is attacked. On his own initiative, Churchill led the effort to rescue the train, including directing efforts to move derailed cars so the engine was able to make it back to friendly lines. Churchill was left behind and taken prisoner.

The remainder of the work recounts Churchill’s seizure and imprisonment, and subsequent escape. Plotting with several officers, he is first over the iron paling, impatient to launch the escape. Incredibly, a combination of hopping a train and hiking on foot and hiding in the veld brings him at last to the one man in that whole area who could help, unbeknownst to him when he approached the house of mine manager John Howard, one of the few British allowed to remain because of his indispensable role of running the mine at Delago Bay. After hiding him for a time in the mine, and in a secret part of his office, he secrets him into a shipment of wool to Lourenco Marques, Portuguese territory with a British embassy. Despite searches combing the country, Churchill makes it, becomes a hero, and then gains a military appointment and is among the troops liberating his former fellow prisoners.

Any who follow my reviews know I’m a fan of Churchill, and also the work of Candice Millard, whose previous works Destiny of the Republic (review) and The River of Doubt (review), I thoroughly loved. Millard has a way of ferreting out lesser known events in the lives of great personages, whether it was the medical malpractice and the crazed assassin behind the death of James A. Garfield, or Teddy Roosevelt’s perilous journey down an unexplored South American river, from which he nearly died. Those focused on events toward the end of her subject’s lives. This book reveals the rise of a young man, through an improbable escape and subsequent military exploits, and his reports of them that set him on the path of greatness.

This was a book that made me wonder about a word Millard has used elsewhere — destiny. Yes, we have Churchill himself, never in doubt that he was destined for great things but merely impatient to get there. But the other side of destiny is that he survived at all. In one battle, he rides into the middle of the fray on a white horse, men dying all around him, as well as the horse under him. Again and again, in the train attack, and subsequently in battle, he emerged unscathed, and not for the last time. That Churchill made it to freedom, even that he sought help in the one place that would give it to him makes one wonder at the Providence that watched over this man and brought him to prominence in Britain’s darkest hour.

Share this: