My rating: 5 out of 5 stars

My rating: 5 out of 5 stars

Date read: 21 October 2017

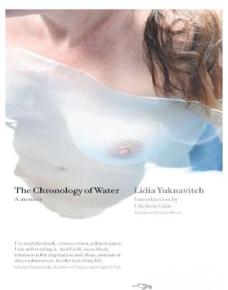

Published by Hawthorne Press, 2011

Verdict: Absolutely unbelievably brilliant.

Find it on Goodreads.

This is not your mother’s memoir. In The Chronology of Water, Lidia Yuknavitch expertly moves the reader through issues of gender, sexuality, violence, and the family from the point of view of a lifelong swimmer turned artist. In writing that explores the nature of memoir itself, her story traces the effect of extreme grief on a young woman’s developing sexuality that some define as untraditional because of her attraction to both men and women. Her emergence as a writer evolves at the same time and takes the narrator on a journey of addiction, self-destruction, and ultimately survival that finally comes in the shape of love and motherhood.

I am in awe with this work of art; I do not know how to find the words to adequately explain why I loved this so much. How about this:

- Lidia Yuknavitch is unflinchingly honest: her destructive tendencies, her flaws, mistakes, triumphs, loves are laid bare for the world to see.

- Her command of language is mesmerizing.

- I could feel every emotion possible while reading this.

- She is a hero. But also highly unpleasant.

Earlier this year I reviewed Hunger by the amazing Roxane Gay; that book set the bar high for what a memoir could do – this book is similar in a way. It reads like a novel but has the emotional impact of raw, undiluted, real pain. Both women use art as a channel to deal with their deep and debilitating pain, both create works of absolute stunning beauty.

Lidia Yuknavitch tells of her life, of growing up in a household with an abusive father and a mother who slowly succumbed to alcoholism, of finding solace in competetive swimming, of failing university twice, of drug addiction, of the death of her child, of her two spectacularly failed marriages. She fucks up, a lot. She is undeniably awful, mostly to herself, often to others. She claws her way out of darkness so deep it seems to swallow her whole again, and again, and again. Her self-destructive tendencies are mesmerizing in their scope and her honesty is unflinching.

She tells this in short, fragmented chapters, with poem-like language that cuts deep and had me reeling. Always circling back to water and art, the two things that saved her. Her inventive way of using language and creating imagery alone would be enough to make this a near perfect book, her ability to channel her trauma into something this beautiful and stunning makes it my favourite of the year.

First sentence (of the acknowledgements): “If you have ever fucked up in your life, or if the great river of sadness that runs through all of us has touched you, then this book is for you.”

Advertisements Teilen mit: