I always feel that book lovers can sometimes fall into a bit of a predicament when it comes to gifts. I love books, and if there’s a birthday or a celebration coming up and I’m lucky enough to have someone who wants to buy me a present, chances are I’m going to want them to be of the bookish variety. Where it gets tricky is with the fact that everyone knows how much of an avid reader I am, meaning that the vast majority of people are either too scared to buy me a book in case I already have it, or they feel that I already have enough books (crazy talk!). I think anyone can agree that it’s just not as fun when you help pick your own presents, and I would almost always rather be surprised with a book.

I always feel that book lovers can sometimes fall into a bit of a predicament when it comes to gifts. I love books, and if there’s a birthday or a celebration coming up and I’m lucky enough to have someone who wants to buy me a present, chances are I’m going to want them to be of the bookish variety. Where it gets tricky is with the fact that everyone knows how much of an avid reader I am, meaning that the vast majority of people are either too scared to buy me a book in case I already have it, or they feel that I already have enough books (crazy talk!). I think anyone can agree that it’s just not as fun when you help pick your own presents, and I would almost always rather be surprised with a book.

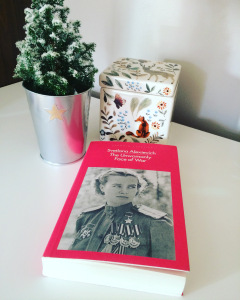

The one person who is undeniably brilliant at this is my boyfriend. He has an uncanny ability of picking books I’ve either had my eyes on, or that I’ve never seen before but fall instantly in love with. It was recently my birthday and he really did out do himself. He’d heard me saying that I wanted to read some more historical non-fiction and he gave me the best surprise by gifting me two such books that I had never before heard of. Needing to instantly devour them, I decided to start with Svetlana Alexievich’s The Unwomanly Face of War, with my edition being translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. This book is essentially an oral history of a vast array of women from the Soviet Union who fought against the Germans’ during the Second World War. It blends together brilliantly the vulgar truth of war and the structures we impose where gender is concerned, all the while focusing upon fascinating and small details which are often overlooked in favour of the more obvious male heroics of war. I have somewhat of an obsession with world war two literature and love exploring gender in society, so this was always going to a must have!

Alexievich actually won the 2015 Novel Prize in Literature for this masterpiece, and within the first few pages I could immediately see why. She has a very unique style of writing, described as ‘polyphonic’ writings which bring together a ‘chorus of voices to describe a specific historical moment’. There really is no better or more acutely accurate description than this. This whole book is almost set up like a document, with the author herself explaining how she set about establishing the book and gathering the information. What’s really the main substance of the book is the combined plethora of memories told directly by the women. Firstly, we have the shorter anecdotes from various women which tell both surprising and poignant memories in a very condensed yet powerful space. Secondly, we have some longer and more specific case studies of one individual which might take a deeper look at how they entered the war and spent their time during it. In theory this book should have seemed like a task far to epic to achieve, a cast of people far too numerous and memories far too painful and raw to reveal, yet Alexievich has pulled it off to perfection.

Alexievich had contacted and interviewed a staggering amount of people during the making of this book and is clear to see that this is a book with a purpose. As she herself puts it:

‘I write not about war, but about human beings in war. I write not the history of a war, but the history of feelings. I am a historian of the soul’ (p. xix).

Alexievich is not giving us an academic and clinical overview of the events of the war. We do not focus upon the logistic and politics. We do not focus upon the heroic deeds and the shows of valour against the enemy which has been depicted to the world for effectively. This is a book which focuses on the small minutiae of war; the little moments which in turn lead to the brave deeds which we read of in absolute horror today. Even more outstanding is the beauty within the book; the moments of real honesty which carry this thread of poignancy throughout its entirety. Alexievich writes with great passion and beauty, but she does an equally perfect job of transcribing the words of these women onto the page.

Throughout this book we see just some of the ways in which the author acquired these stories, learning about how she met these people and the ways in which they divulged a past which had often been so closely guarded. Alexievich asks the question ‘But why?’ ‘Why, having stood up for and held their own place in a once absolutely male world, have women not stood up for their history?’. She writes that ‘a whole world is hidden from us’ (p. xiv), and what’s so startling is this very truth. Think of someone who has served in the war, an individual decorated with medals for their deeds, and almost certainly that person will be male. Reading this book totally changed my horizons, illuminating so vividly the plethora of women who not only served, but fought side by side with the men. Women who killed just as frequently and faced equal terror for their country.

Alexievich admits that it was not always easy gaining access to such memories, that many wished to forget the parts they had played in the war. Some were even fearful that their family, their daughters in particular, would read of their actions. Likewise she mentions the difficulties in gaining an accurate account of events played out so long ago. Attention is given to the fact that the years have influenced people and shaped their perspective of things. She writes how:

‘Just after the war this woman would have told of one war; after decades, of course, it changes somewhat, because she adds her whole life to this memory’ (p. xviii).

Her remembrance of an event might have been tampered somewhat by her own self, coloured by all that she has seen and done since. I think this is true of all those who have fought or existed during a war, but specifically so of women. This book takes a fascinating look at gender and how a woman appropriated a male role during the war. Yet, once the war is over, where does this leave such a woman? Can she retreat once more into the domestic sphere, reclaim again the characteristics of a stereotyped weaker sex, when she has experienced what society deems as making a man? In order to call herself once more a woman, must she forfeit everything she has accomplished during the war? The book examines this idea, seeing how many women are almost afraid to remember such days, to relive the ways in which they forsook what was perceived as their femininity. Additionally we have fascinating examples of the part a husband can play in ensuring a woman remembers the ‘correct’ version of the war. In this book we have men who coach their wives on the correct things to say to the author, providing maps to be memorised and key events to be discussed. ‘The men were afraid that women would tell about some wrong sort of war’ (p. xxii), but did the women not experience the same things in many cases?

The female body is also a theme which is revisited time and time again across this book. Whilst the author states that it can be more unbearable and unthinkable for a woman to kill because a ‘woman gives life’ and ‘bears it in herself for a long time’ (p. xxi), there is still a multitude of women in this who have killed. During the war they became physical symbols of the male world they have entered; their hair is cut, they are forced to wear male clothing and even their biological periods stop in such a stressful environment. A man is quoted as denying that a woman is indeed a woman. He replies, ‘No, she’s a soldier. She’ll be a woman again after the war’ (p. 164). The sentence is so flippant, as if an individual can change their gender based upon the need society calls for. Many of the men within this book admire the women, are proud of them, but this pride does not always allow for such women to reclaim a feminine role. After the war many of the men we learn about cannot reconcile such women to be figures of femininity; they are too masculine. As you can probably tell, the book really is a riveting look at the social ideologies surrounding gender and the impact which war has upon this.

Despite the above, we must remember that most of these women were not forced to go to the front; many of them wanted to go, feeling the desire to protect the Motherland as fiercely as the men themselves. Many of them left school, lying about ages and running away from home to make their way into a war. Looking at it from a privileged contemporary view point it’s impossible to image anyone wanting to enter into war, let long young women who have barely started their lives. One moment which really moved me was when a woman commented on the fact that she actually grew in the war, several inches in fact. She quite literally moved from a child to a woman whilst faced with the continual threat of death, and of course this is a topic which is sadly a current political topic even today.

I think the thing I loved most about this book was quite simply reading about the small details which, for many of the women, are what they remember so vividly about the war. Much of what we learn are personal details which many people would never really waste time on, but its these small moments which really bring this history to life. The author writes that she is ‘trying to bring that great history down to human scale, in order to understand something’ (p. 139), and she’s done a commendable job. What we’re left with is this merging of the familiarity of life and domesticity, against the total unrecognisable horror of war. It’s emotional. It’s violent. It’s sad. It’s beautiful. Most importantly, it’s real. One scene that sticks in my mind is when our author asks a foot soldier what the most frightening thing in the war was. She replies that the expected answer is ‘death’ (p. 65), but that she has a different answer:

‘For me the most terrible thing in the war was – wearing men’s underpants. That was frightening . . . . well, first of all, it’s very ugly . . You’re at war, you’re preparing to die for the Motherland, and you’re wearing men’s underpants. Generally, you look ridiculous. Absurd.’ (p. 65).

It’s a completely unexpected answer, and one which you’d probably never consider unless you’d been in that position. We get such unique case studies which all share the backdrop of war and are equally as interesting, but we must also remember that this book was initially stopped from being published. The details within it went against what the official record of history showed, the bravery and dignity of the winning side. A lot of what Alexievich collected was then later the victim of censorship. A particularily vidid example was that of a woman who had recently given birth and who was fighting in the war. Finding herself and her comrades surrounded by Germans, the mother actually kills her baby to stop any cries which may alert the Germans. To consider such a thing as reality is unbearable, but it is true. Sadly, such illustrations of the true nature of war are often restricted; we want only the bits to be proud of, and not the ugly truth.

I would recommend this book wholeheartedly to everyone, regardless of whether you enjoy reading. Not only is it a crucially important and knowledgeable insight into history, but it is also a fascinating and enthralling read. I also think it would be a great read to pick up if you’re looking for accessible non-fiction, as it is so easy to establish an emotional connection to the wealth of real people. Likewise, as I am born and bred in the UK, I think it provided me with so much unknown information about what the war was like from the Soviet Union perspective, which we sadly don’t really learn about.

It’s so easy to forget the things that society as a whole demanded of our men and women and the terrible circumstances we created. As Svetlana Alexievich so astutely writes:

‘It’s terrible to remember but far more terrible not to remember’.

Publisher: Penguin Classics

Rating: 5*/5*

Advertisements Share this: