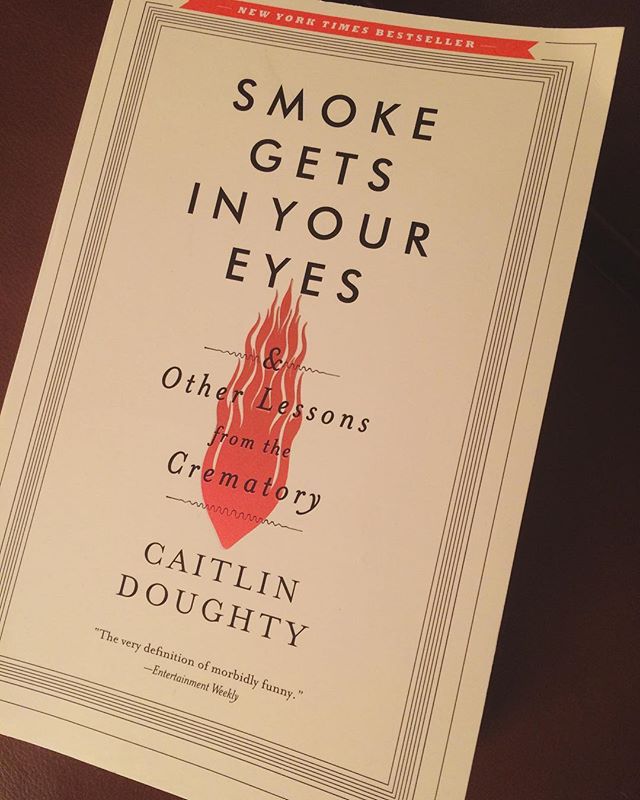

Caitlin Doughty founded The Order of the Good Death as a way for people to seek acceptance surrounding death—that of their loved ones, and themselves. She works as a mortician, green funeral advocate, and hosts a YouTube series called Ask a Mortician. But in 2008, Doughty was a hapless twenty-three year-old crematory operator, clumsily pursuing her start in what many would dub an undesirable or morbid industry. Death is a part of life—inevitable and unchanging. Whether or not we have direct experience in witnessing a death or have spent any time with corpses outside of their satin-lined caskets, we see how death profoundly affects and changes those around us, and we will all someday experience it ourselves: When it comes to death, everyone gets a turn.

Caitlin Doughty invites us into her world through this darkly funny memoir, sharing her experiences in her first years in the death business. Grief, gore, and a thin film of “people dust”— they’re all here for the telling. Such is a job not everyone is suited to—clearly, something in Doughty has called her to the world of death, and she has made it a lifelong endeavor. Doughty describes witnessing, at the age of eight, the accidental death of a child. We all have catalyst moments in our lives, where an internal seismic shift occurs and informs the direction our future lives might take. In college, Doughty majored in medieval history with a concentration on death and culture. Her application to Westwind Crematory and Funeral Home was her way of getting closer to her fascination with the death, working directly with the dead as a crematory operator.

To state the obvious: Smoke Gets in Your Eyes is not a read for the faint of heart (or stomach). Doughty vividly describes the condition of bodies in various states of decay, the process by which cremation is complete, and a host of other tantalizing morbid tidbits. I myself am somewhat morbid: frequently contemplating my own untimely (or timely) demise, what might be done with my body postmortem, the natural process of decay and the unnatural practice of embalming. When it comes to death, I am all “tell me more;” I’m leaning in, hushed and attentive, hanging on every word.

“The people in the [refrigerated body storage area] would probably not have hung out together in the living world. The elderly black man with a myocardial infection, the middle-aged white mother with ovarian cancer, the young Hispanic man who had been shot just a few blocks from the crematory. Death had brought them all here for a kind of United Nations summit, a round-table discussion on nonexistence” (Doughty, 13).

Modern society has a way of sanitizing death—removing us from it, “protecting”

us from the unsavory sights (and/or smells), whisking the deceased away the moment they pass away for their brief layover at the funeral home for the requisite (or is it?) embalming followed by interment. Why don’t we think about these practices more—question what happens to our loved ones corpses, what might happen to our own? Doughty’s tone is refreshingly absent of the spiritual platitudes that can so often surround death. There are no promises of eternal bliss in the hereafter. Instead, Doughty gently shows us what actually goes on after death, and how it affects the living. She is sincere, yet possesses a dark humor that makes Smoke Gets in Your Eyes a delightfully compelling read. If you fear death (and we all do, on some level), please read this book.